This past month, there was a free production of Richard III in New York’s Shakespeare In the Park, starring Danai Gurira as the title character. I have not seen this production, though I wish I had. I enjoyed the actress Ms. Gurrira in such films as “Black Panther,” and would love to see her do Shakespeare. What is more, the concept intrigues me. This project explores themes of toxic masculinity, racial identity, inferiority, and misogyny.

https://www.npr.org/2022/07/10/1110359040/why-it-matters-that-danai-gurira-is-taking-on-richard-iii

Unsurprisingly, with so many heady topics in the production, this Richard III is still somewhat controversial. Some right-wing critics dismissed the whole production as a piece of ‘woke propaganda,’ but I feel this is unfair.

When Danai Gurira of Marvel’s “Black Panther” first takes the stage in the title role, the actress has no perceivable hunchback or arm trouble. And yet the dialogue suggesting Richard suffers from a lifelong physical issue (“rudely stamped”) has been kept in. Perhaps we are to use our imaginations. Who knows? We are certainly tempted to close our eyes.

By Johnny Oleksinski

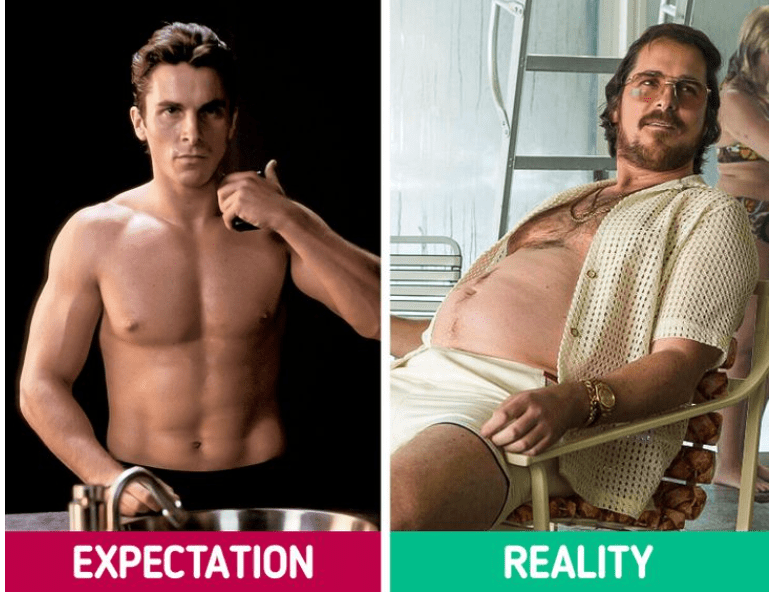

I will not judge this production based on the acting because I haven’t been able to see it. What I will do is take a stance on the validity of the concept. Specifically, I want to ask if this play is a good examination of toxic masculinity and if it would it be worthwhile to see it portrayed by a black woman, as opposed to a white man. The short answer is an emphatical “Yes.”

Richard’s Toxic Masculity

Richard III is definately an example of toxic masculinity. He is violent, full of hatred, vengeance, and mysogeny. He is constantly insulting women from Lady Anne, Jane Shore, Queen Elizabeth, and even his own mother. In fact, the source of Richard’s toxic attitude is that he blames his mother for his disability and deformity:

Well, say there is no kingdom then for Richard;1635

What other pleasure can the world afford?

I'll make my heaven in a lady's lap,

And deck my body in gay ornaments,

And witch sweet ladies with my words and looks.

O miserable thought! and more unlikely1640

Than to accomplish twenty golden crowns!

Why, love forswore me in my mother's womb:

And, for I should not deal in her soft laws,

She did corrupt frail nature with some bribe,

To shrink mine arm up like a wither'd shrub;1645

To make an envious mountain on my back,

Where sits deformity to mock my body;

To shape my legs of an unequal size;

To disproportion me in every part,

Like to a chaos, or an unlick'd bear-whelp1650

That carries no impression like the dam.

And am I then a man to be beloved?

O monstrous fault, to harbour such a thought!. 3H6, Act III, Scene i, lines 1635-1653.

Now I should clarify the difference between deformity and disability, which are characteristics that Richard III has as part of his character makeup. According to the Americans With Disabilities Act, a disability is defined as: “A physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities.” This could include paralysis, autism, or any number of congenital or acquired conditions. Richard’s disability is primarily his limp (caused by his unequally shaped limbs), and his withered arm. What’s interesting in this production is that while the title role is played by an able-bodied woman, most of the rest of the cast have actual disabilites. Watch this clip of the famous courtship scene between Richard and Lady Anne, who plays her role in a wheel-chair.

While a disability is a legal term that is recognized by lawyers and governments alike, the term “deformity” is more subjective; it generally refers to any kind of cosmetic imperfection. In Richard III, this applies to Richard’s hump and withered arm.

The Elizabethans thought that deformity was a sign of disfavor from God, and that deformed people were constantly at odds with God and nature, as Francis Bacon puts it in his essay, “On Deformity.”

As deformed people are physically impaired by nature; they, in turn, devoid themselves of ‘natural affection’ by being unmerciful and lacking emotions for others. By doing so, they get their revenge on nature and hence achieve stability.

Richard III has this drive for revenge in spades and I believe it manifests itself as a particularly terrible form of toxic masculinity. Richard definitely wants the crown to make up for his lack of ‘natural affection,’ but he is also especially malevolent towards women.

I, that am rudely stamp’d, and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph;

And therefore, since I cannot prove a lover,

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days

Seeing a woman play this kind of misogynist dialogue forces the audience to take it out of context and question Richard’s point of view. We see casual misogyny every day, and seeing a woman deliver it is quite illuminating.

Richard’s deformity and Blackness

Another provocative choice by Danai Gurira’s portrayal of Richard is the fact that she plays the role of Richard without the hump or withered arm. She herself explains that for her production, Richard’s perceived deformity, is actually represented by her being a black woman:

He’s dealing with the otherness compared to his family, in terms of not being Caucasian and fair like them.” The word ‘fair’, is used a lot in the play.

Danai Gurira’s

Shakespeare writes Richard as constantly striving to compensate for his deformities by being clever, violent, and eventually, by becoming king. As I wrote before in my review of Othello, for centuries black people have been portrayed as inferior; aberrations of the ‘ideal fair-skinned form’. So, to the Elizabethans, blackness itself was a form of deformity, and the rawness of addressing this uncomfortable fact in this production should be commended.

English people are already trained—and we have scholars like Anthony Barthelemy has talked about this in his book Black Face, Maligned Race, where the image of blackness, as associated with sin, with the devil, all of these things, makes it quite easy to map onto then Black people these kinds of characteristics. Then, those kinds of characteristics allow for the argument that these people are fit to be enslaved. – Dr. Ambereen Dadabhoy, Race and Blackness in Elizabethan England Shakespeare Unlimited: Episode 168

https://www.folger.edu/shakespeare-unlimited/elizabethan-race-blackness-dadabhoy

So while I can’t speak to the production’s acting or staging, I will emphatically defend the notion that this production’s concept is valid. Richard III is an example of toxic masculinity through his self-hatred, violence, misogyny, and narcissism. In addition, as I’ve written before, in the Early Modern Period, blackness was considered an aberration or deformity, and seeing it in the person of Richard, with the implicit understanding that black people still face this kind of prejudice today, opens a much-needed dialogue that any production of Shakespeare shouldn’t be afraid to open.

In short, by re-contextualizing Richard’s deformity and disabilities, this production gets to the heart of the play’s moral for our times. The early modern period’s toxic attitudes towards deformity and disability created the Renaissance monster of Richard III. We in the 21st century must examine our own societal prejudices and toxic attitudes so this monster does not come to haunt us in real life.