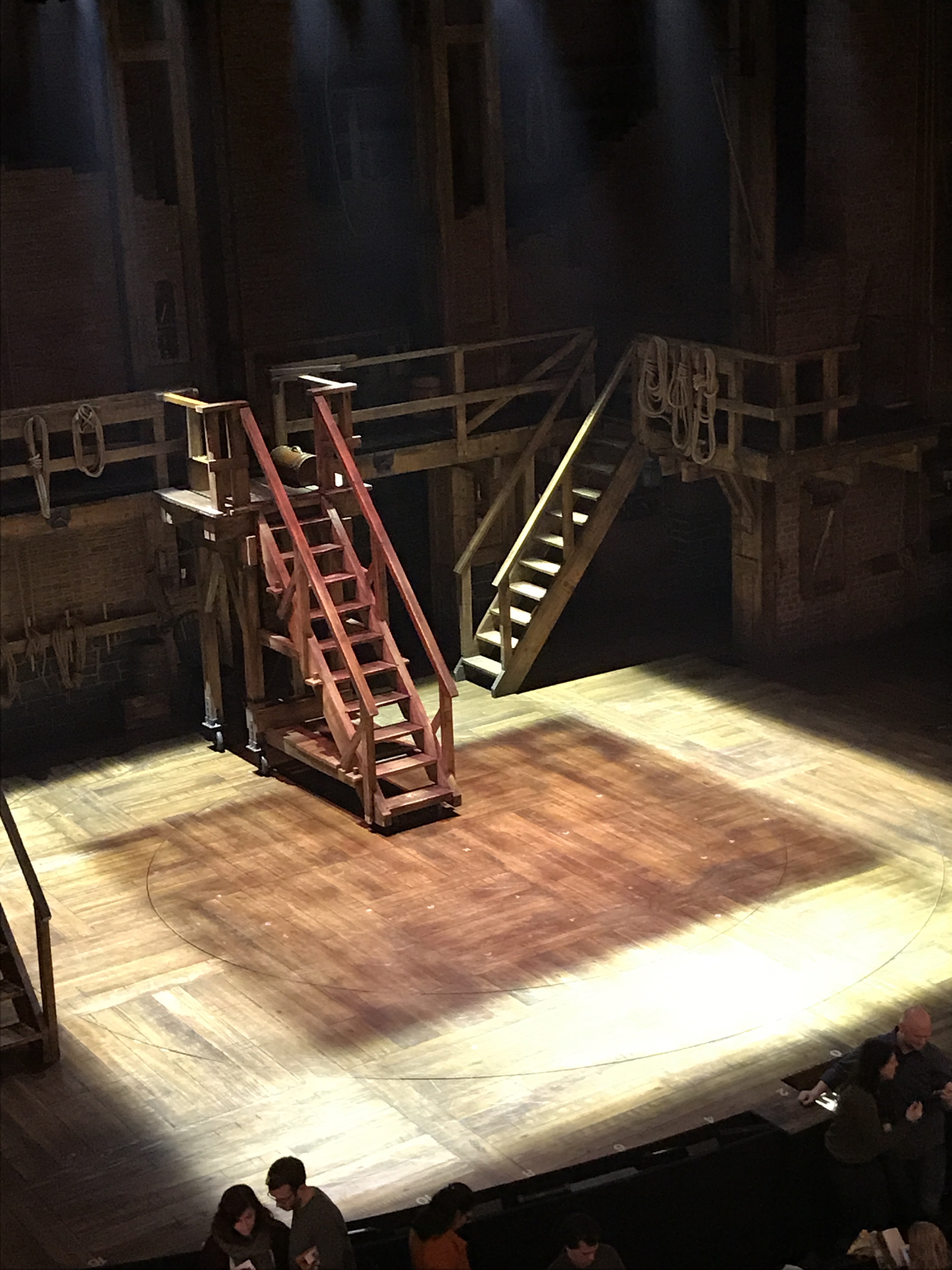

If you have two ears, you’re probably familiar with the Broadway Musical Hamilton. It swept the Tonys, has opened up touring productions across the country, and there’s already talk of a movie.

This historic American musical was the brainchild of writer Lin Manuel Miranda, who also originated the role of Alexander Hamilton.

The show is incredibly smart, creative, and delves into the seminal moments of American history.

What’s really exciting to me is that Hamilton also has a depth and complexity that mirrors some of Shakespeare’s greatest plays, specifically the history plays.

Between about 1590 and 1613, Shakespeare wrote 10 plays about the lives of English kings, from the vain Richard the Second to the heroic Henry the Fifth, to the diabolical Richard the Third. Here is a list of Shakespearean history plays, with links to online study guides, listed in chronological order by reign, not publication date.

- King John

- Richard the Second

- Henry the Fourth, Part I

- Henry the Fourth, Part II

- Henry the Fifth

- Henry the Sixth , Part I

- Henry the Sixth , Part II

- Henry the Sixth , Part III

- Richard the Third

- Henry the Eighth

Are these Shakespearean history plays historically accurate by our standards? No, not by a long shot, though Shakespeare is only partially to blame for that. While Lin Manuel-Miranda had Hamilton’s own essays, his letters from friends and loved ones, and of course, every American history book at his disposal, Shakespeare’s sources were few, and mostly propaganda. They were, (to paraphrase Napoleon and Benjamin Franklin), “A series of lies, composed by winners, to excuse their hanging of the losers.”

Shakespeare’s genius however, was to turn these two-dimensional propaganda stories into three dimensional characters with which we can all identify. Miranda did the same thing in reverse- distilling his wealth of historical information into a universal story of a man’s quest for the American Dream. Hamilton went from being an immigrant, to a soldier, to a pioneer in American law, government, and finance and the musical reflects his struggle to achieve his dreams through each stage of his life. It is also a love song from America to a man who dreamed of a future for America, one not dissimilar to the ode Shakespeare wrote to his “Star of England,” Henry the Fifth. The greatest compliment I can give Miranda is to say that he created an American musical, with the scale and breadth of Shakespeare.

Part I: War and Peace

In Shakespeare’s histories, particularly the first tetracycle of plays that include Richard the Second, the three parts of Henry VI, and Richard, III, there is a constant shift between war and peace, as scholar Robert Hunter observes. These plays cover the 200 year period of Wars of the Roses, and the end of the Hundred Years War. In all of these plays there are some very violent and very opportunistic young men who see war as an opportunity to rise above their stations. In war, they win glory in death, honor, respect, and status in life. However, in peacetime, they have “no delight to pass away the time,” as Richard III observes, and they struggle to survive in the political landscape of peace.

Hamilton is a man of this same mold: When we first meet him, he is a poor immigrant from the West Indies with no title or money to improve his status. He spends the first third of the musical wishing he could become a commander in the Revolutionary War, especially in the song: “My Shot”

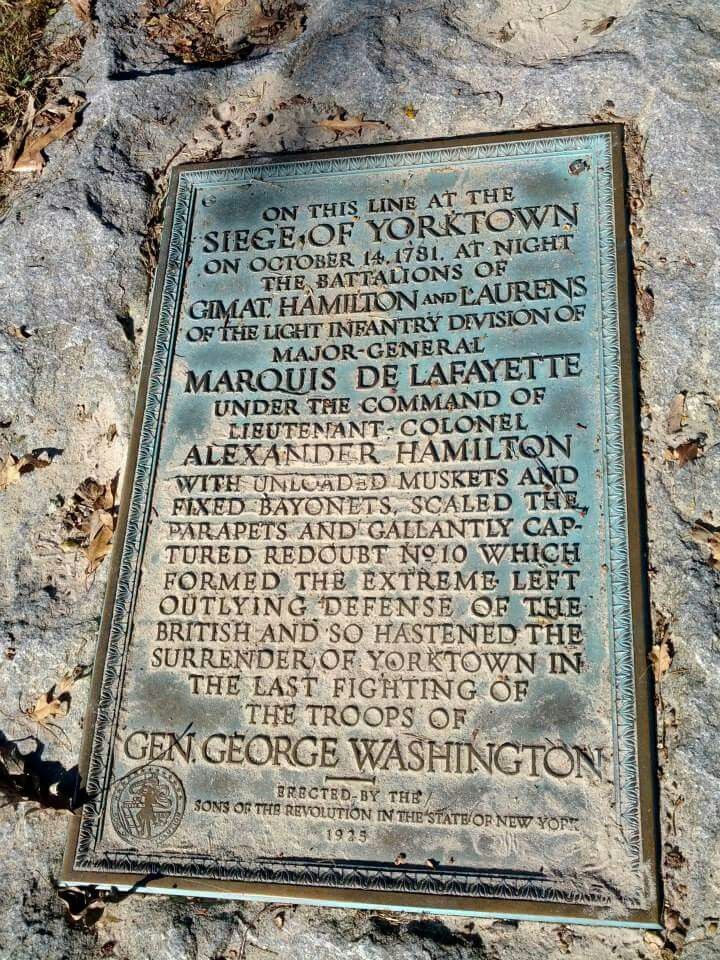

Once Hamilton joins the revolution, his fortunes start to improve; he becomes George Washington’s aide-de-camp, then becomes a war hero in the Battle of Yorktown, and marries Eliza Schyler, daughter of one of the wealthiest men in America.

Hamilton in war bears similarities to Shakespearean characters like Hotspur, Richard Duke of York, and even Richard III; people who see war as a chance to either die in glory, or become honored, wealthy, and powerful.

Unfortunately for Hamilton, he fares less well once the war ends. Even though he becomes Washington’s first Secretary Of the Treasury, his success and closeness to now-President Washington makes him a walking target to his political adversaries. Even worse, his ambition and inability to compromise makes Hamilton equally vulnerable to people who see him as a loudmouth, an elitist, and a would-be demagogue who wants to control America’s finances and live like a king, similar to the way the British Prime Minister controls England’s finances.

The character Hamilton resembles most in peacetime is Cardinal Wolsey in Shakespeare’s Henry VIII.

I happen to know a lot about this character since I played him back in 2008. Wolsey controlled Henry VIII’s finances and was hated by most of Henry’s court because he was the son of a poor butcher in Essex, and became the king’s right-hand man. Throughout Shakespeare’s play, the lords of court are whispering about how Wolsey really controls the government; they even call him the ‘king cardinal’!

The real life Wolsey appears to have been hated just as much by Henry’s lords. Just look at the faces of the people of the court in this painting of the king and Wolsey by Laslett John Pott; the lords on the right are clearly jealous of Wolsey’s closeness to the king.

In both plays, Washington and King Henry are treated like gods- invulnerable, aloof, and completely above reproach.

Whenever anything bad happens in the play or musical, the legislature blames Wolsey and Hamilton, not the King or the President. Also, in both plays each one falls from grace and is destroyed by his enemies when the king and president no longer supports their right-hand-men.

Wolsey and Hamilton both fall because of their position as the financial advisor, which makes them a target to their enemies. Both are accused of using their country’s finances to enhance their personal wealth, which leads him to scandal and disgrace.

In Henry the Eighth , Wolsey is certainly guilty of conspiring to use his country’s wealth to line his own pockets- he pays the cardinals in Rome to influence their vote in the hopes that he will become the next Pope!

CARDINAL WOLSEY

What should this mean?

What sudden anger’s this? how have I reap’d it?

He parted frowning from me, as if ruin

Leap’d from his eyes: so looks the chafed lion

Upon the daring huntsman that has gall’d him

Then makes him nothing. I must read this paper;

I fear, the story of his anger. ‘Tis so;

This paper has undone me: ’tis the account

Of all that world of wealth I have drawn together

For mine own ends; indeed, to gain the popedom,

And fee my friends in Rome. O negligence!

Fit for a fool to fall by: what cross devil

Made me put this main secret in the packet

I sent the king? Is there no way to cure this?

No new device to beat this from his brains?

I know ’twill stir him strongly; yet I know

A way, if it take right, in spite of fortune

Will bring me off again. What’s this? ‘To the Pope!’

The letter, as I live, with all the business

I writ to’s holiness. Nay then, farewell!

I have touch’d the highest point of all my greatness;

And, from that full meridian of my glory,

I haste now to my setting: I shall fallLike a bright exhalation in the evening,

And no man see me more. Henry the Eighth Act III, Scene ii.

Again, though Wolsey is guilty, like Hamilton he also used his financial genius to bring England into a new age of prosperity after centuries of war. The Tudors were some of the richest and most powerful monarchs in British history, and Wolsey helped establish their dynasty, but thanks to his enemies, he is turned out of court in disgrace:

O Cromwell, Cromwell!

Had I but served my God with half the zeal

I served my king, he would not in mine age

Have left me naked to mine enemies. Henry VIII, Act III, Scene ii.

Hamilton is also accused of embezzling his wealth by his enemies, including James Madison, and Thomas Jefferson

Hamilton’s enemies argue that his banking system benefits New York, where Hamilton was part of the House Of Representatives, as well as the Constitutional Convention. The main difference between Wolsey and Hamilton is that he didn’t embezzle America’s money, he is actually guilty of a far worse sin- adultery. Hamilton is accused of having an affair, and embezzling funds to keep it quiet, which he denies in a spectacular fashion:

In both plays, the moment where the main character begins to fall is dramatized in a stirring, metaphor-rich soliloquy. Wolsey compares himself to the Sun, who, once he reaches the zenith of the sky, has nowhere to go but down to the west, and set into night.

Hurricane From “Hamilton: An American Musical. Reposted from Deviant Art.com

Hamilton compares his situation to being in the eye of a hurricane, a particularly apt metaphor, since the real Alexander Hamilton’s house was destroyed by a hurricane in 1772. In addition, Lin Manuel Miranda‘s parents come from Puerto Rico an island that has, (and continues to be,) ravaged by hurricanes.

In the song, “Hurricane,” Hamilton remembers that when he lost everything as a boy in 1772, he beat the hurricane by writing a letter which was published in the newspaper, and inspired so much pity that the residents of the island raised enough money to send Alexander to America.

Later in the song, Hamilton decides to try to soothe the political hurricane that has engulfed him by writing a pamphlet, admitting the affair, but denying any embezzlement. Eventually the scandal destroys Hamilton’s career, but it doesn’t destroy his life; for that we have to look at the Shakespearean rivalry between Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

Part II- The Duel: Hamilton and Burr V Henry and Hotspur.

Aaron Burr and Hamilton keep meeting at important moments in the show, as if their fates are intertwined like gods in some kind of Greek tragedy.

Hamilton and Burr appear as polar opposites in the musical. Hamilton is fiery, opinionated, uncompromising, and highly principled. He ruffles feathers, but his supporters know where he stands. Burr is the opposite. He keeps his views to himself, and waits for the most opportune time to act on anything. Throughout the play, Hamilton and Burr hate and admire different things about each other. Hamilton admits that Burr’s cool practicality helps him to practice the law and succeed in politics, while Burr admires Hamilton’s energy and his ability to work and write as if his life depends on it, especially in the song “The Room Where It Happens.”

After Hamilton endorses Jefferson in the election of 1800, Burr loses the race, and the job of Vice President. In the musical, he blames Hamilton, and their grievance grows into a deadly conflict.

The rivalry between Hamilton and Aaron Burr mirrors many characters in Shakespeare, but the two I want to focus on here are Hotspur and Prince Hal from Henry the Fourth Part One

As this video from the Royal Shakespeare Company shows, these two combatants meet only once in the play, but they are constantly compared to each other by the other characters, who talk about them as if they were twins, (they even have the same first name)! Even the king remarks that his son could have been switched at birth with Hotspur.

Prince Henry (known as Hal in the play), is the heir to the throne. Like Burr in Hamilton, Hal is methodical, cool, keeps his feelings to himself, and is known by some as a Machiavellian politician. Hotspur, (or Henry Percy), is his opposite. Like Hamilton he is fiery, eloquent, and not afraid to die for his cause, which in Hotspur’s case is to supplant the royal family and correct what he believes is an unjust usurpation by Hal’s father, King Henry the Fourth.

In the scene below, the two men seem hungry to not only kill one another, but to win honor and fame as the man who killed the valiant Henry. Whether it’s Henry Percy, or Prince Henry who will die, is something they can only find out by dueling to the death.

HOTSPUR

If I mistake not, thou art Harry Monmouth.

PRINCE HENRY

Thou speak’st as if I would deny my name.

HOTSPUR

My name is Harry Percy.

PRINCE HENRY

Why, then I see

A very valiant rebel of the name.

I am the Prince of Wales; and think not, Percy,

To share with me in glory any more:

Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere;

Nor can one England brook a double reign,

Of Harry Percy and the Prince of Wales.HOTSPUR

Nor shall it, Harry; for the hour is come

To end the one of us; and would to God

Thy name in arms were now as great as mine!PRINCE HENRY

I’ll make it greater ere I part from thee;

And all the budding honours on thy crest

I’ll crop, to make a garland for my head.HOTSPUR

I can no longer brook thy vanities.

They fight, HOTSPUR is wounded, and falls

HOTSPUR

O, Harry, thou hast robb’d me of my youth!

I better brook the loss of brittle life

Than those proud titles thou hast won of me;

They wound my thoughts worse than sword my flesh:

But thought’s the slave of life, and life time’s fool;

And time, that takes survey of all the world,

Must have a stop. O, I could prophesy,

But that the earthy and cold hand of death

Lies on my tongue: no, Percy, thou art dust

And food for– Dies.

Hamilton’s duel is also a matter of honor; Alexander wants to defend his statements against Burr, while Burr wants to stop Hamilton from frustrating his political career. Here is how their duel plays out in the musical Hamilton:

Just like Burr, Prince Hal feels remorse after killing his worthy adversary.

PRINCE HENRY

For worms, brave Percy: fare thee well, great heart!

Ill-weaved ambition, how much art thou shrunk!

When that this body did contain a spirit,

A kingdom for it was too small a bound;

But now two paces of the vilest earth

Is room enough: this earth that bears thee dead

Bears not alive so stout a gentleman.

If thou wert sensible of courtesy,

I should not make so dear a show of zeal:

But let my favours hide thy mangled face;

And, even in thy behalf, I’ll thank myself

For doing these fair rites of tenderness.

Adieu, and take thy praise with thee to heaven!

Thy ignominy sleep with thee in the grave. Henry IV, Part I, Act V, Scene iv.

III. The Times

In both Hamilton and all of Shakespeare’s history plays, the characters know that they are living during important events and their actions will become part of the history of their country, and none more than Washington. In the song, “History has its eyes on you,” he warns Hamilton that, try as one might, a man’s history and destiny is to some extent, out of his control, which echoes one of King Henry the Fourth’s most bleak realizations:

Henry IV. O God! that one might read the book of fate,

And see the revolution of the times

And changes fill the cup of alteration

With divers liquors! O, if this were seen,

The happiest youth, viewing his progress through,

What perils past, what crosses to ensue,

Would shut the book and sit him down and die. Henry IV, Part II, Act III, Scene i.

Washington is keenly aware of his legacy and does his best to protect it. In Shakespeare’s Henry IV,the king also lies awake trying to figure out how to deal with the problems of his kingdom, which is why Shakespeare gives him the famous line “Uneasy lies the head that wears the crown.” Likewise, Richard II, makes a famous speech where he mentions how many kings have a gruesome legacy of dying violently:

As we see the whole story of Hamilton’s life, his fate changes constantly and his legacy shifts in every scene of the show: immigrant, war-hero, celebrated writer, Secretary of the Treasury, but then, once he published The Reynolds Pamphlet, Hamilton went from famous to infamous. After After Burr murdered him in the duel, Hamilton might have been utterly forgotten, in spite of all his great accomplishments. This is a key theme in all history and tragedies; the desire of every man to create a lasting legacy for himself, and thus transcend mortality.

The women who tell the story

Fortunately for Hamilton, the women of his story also help to preserve it. Historically, most of Hamilton’s archives were preserved by his wife Eliza Schyler, and she and her sisters help shape the story from the beginning to the end of the show. Hamilton’s sister in law Angelica sets up this theme by literally rewinding the scene of her first meeting with Alexander, and then retelling how she and Hamilton met from her own point of view.

Once her sister marries Hamilton, Eliza Schuyler asks to “be part of the narrative.” She knows she married a important man and that his life will someday become part of American history. Eliza wants to be a part of that historic narrative.

When Hamilton commits adultery and writes the Reynolds pamphlet though, Eliza is so hurt and scandalized that she rescinds her requests. In the song “Burn,” she destroys her love letters from before the affair, and all correspondence she had with Alexander when he revealed it. Lin Manuel Miranda explained that he wrote the song this way because no records during this period survived, so he invents the notion of Eliza destroying them as a dramatic device, to heighten her estrangement from her husband. Though this is a contrivance, it does re-enforce how, when part of the story is lost, it twists and destroys part of our impression of a person. Shakespeare knew this too; Henry Tudor went to great lengths to destroy the legacy of his predecessor Richard the Third, and literally repainted him as a deformed tyrant. Shakespeare couldn’t escape the narrative of Richard as a monster when he wrote his history play and sadly helped to perpetuate it to this day.

At the end of the play though, Eliza changes her mind yet again, as the final song I placed earlier shows, Eliza spends the last 50 years of her life to preserving and protecting her husband’s name, as well as Washington, all the founding fathers, and children who can grow up knowing that story at her orphanage. This song illustrates clearly that in the end, a man’s story is defined by the people who tell it, and Hamilton is fortunate to have such a creative, energetic and talented writer/ actor in Lin Manuel Miranda, and the cast of Hamilton, to preserve the story in such a Shakespearean way.

Bravo.

Educational links related to Hamilton:

Books

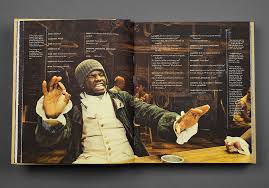

Hamilton: The Revolution by Lin-Manuel Miranda, Jeremy McCarter. A complete libretto of the show, with notes on its creative conception.

Alexander Hamilton by

TV:

“Hamilton’s America” PBS Program. Originally Aired 2016. Official Webpage: http://www.pbs.org/wnet/gperf/episodes/hamiltons-america/ You can watch the full documentary here: http://www.tpt.org/hamiltons-america/

Web:

Biography. Com- Alexander Hamilton:https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.biography.com/.amp/people/alexander-hamilton-9326481

Founders Online: The Papers of Alexander Hamilton: Columbia University, accessed 11/12/17 from https://founders.archives.gov/about/Hamilton

House Of Representatives Biography: Alexander Hamilton- IIhttp://history.house.gov/People/Listing/H/HAMILTON,-Alexander-(H000101)/

Resources on Shakespeare’s History Plays:

Books

- Shakespeare English Kings by Peter Saccio. Published Apr. 2000. Preview available: https://books.google.com/books?id=ATHBz3aaGn4C

- Shakespeare, Our Contemporary by Jan Kott. Available online at https://books.google.com/books/about/Shakespeare_Our_Contemporary.html?id=QIrdQfCMnfQC

-

-

The Essential Shakespeare Handbook - The Essential Shakespeare Handbook by

-

Leslie Dunton-Downer and Alan Riding Published: 16 Jan 2013.

-

-

Will In the World by Robert Greenblatt - Will In the World by Prof. Steven Greenblatt, Harvard University. September 17, 2004. Preview available https://www.amazon.com/Will-World-How-Shakespeare-Became/dp/1847922961

TV:Shakespeare Uncovered: Henry the Fourth. Originally Aired February 1, 2013. Available at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/shakespeare-uncovered/episodes/

Websites

- Howard Ho: How Hamilton workshttps://youtu.be/1qXsFs2ywMo