Since today is the last day of women’s history month I thought I’d talk about the historical first ever Shakespearean actress and first-ever English actress. Margaret Hughes (1630-1719), is credited as the first-ever English actress. She led a fascinating life and books, plays, and movies have immortalized her, including the 2004 film, Stage Beauty.

Although there is some debate among scholars as to whether the 1st actress in question was Margaret Hughe, she is the one who has been credited because of her performance as Desdemona in Othello during the reign of King Charles II.

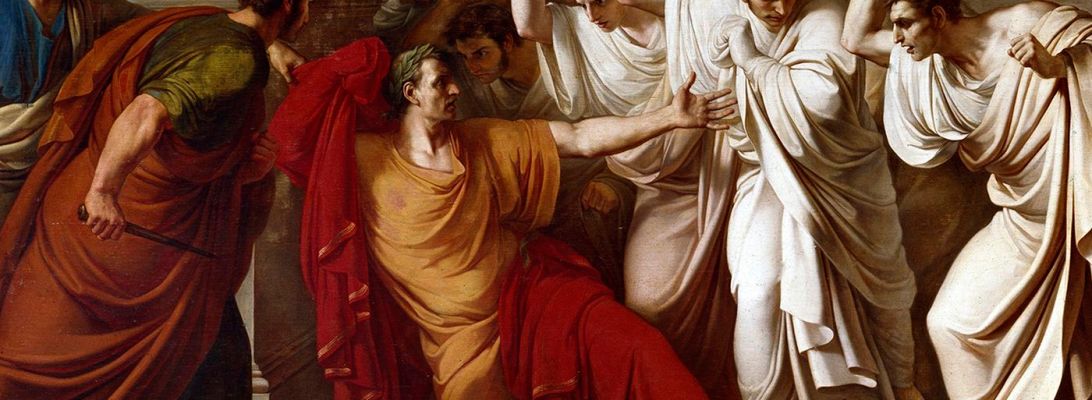

Around 1660s Charles II formally allowed for public performances of women on English stages. Restoration audiences, craving entertainment after the enforced closure of theatres during the Puritan Interregnum, rejoiced. Others, particularly the successful male impersonators of women, were shocked and annoyed as they suddenly lost their celebrity status and were seen as freaks. The stage war that the appearance of actresses initiated resulted in an almost immediate reiteration of almost medieval misogyny and vituperative ostracism directed at any woman who dared to challenge the masculine reign on the English stage. The actresses themselves had to learn both how to act out femininity as seen through male playwrights’ eyes and how to maintain their celebrity status and the audiences’ adoration. This, however, meant more than ‘just’ displaying perfect acting skills and appearing in the best plays available. A successful actress needed to woo the audience, particularly its male members, with her body, or her sexuality in general. She likewise needed to accept, or even engender, vitriolic attacks on her reputation in public discourse and, if possible, utilise such bad publicity to her own advantage. As such, this chapter aims to present a link between medieval anxiety concerning public displays of femininity and the seemingly privileging introduction of the actress in the late seventeenth-century England. It will also present a synthetic image of celebrated actresses’ lives as seen through theatrical records as well as seventeenth-century pamphlets and poetry, proving true the contemporary saying that only lack of press is bad press.

Bronk, 23

What I’m going to do is give a few historical notes on Margaret Hughes and her portrayal of Desdemona in the production of Othello and then I’m going to simultaneously do a review of the movie that celebrates her life: Stage Beauty (which was also made into a play).

Review Of Stage Beauty

What Shakespeare In Love did for the 16th century, this movie does for the late 17th century: it is awash with beautiful costumes elegant sets and dazzling music. it is a visual feast and everybody in it is fantastic in their roles, especially Billy Crudup as Ned Kyneston, Richard Griffith as Sir Charles, Tom Wilkinson as Thomas Betterton, and of course, Claire Danes as Margaret Hughes.

Hughes is a costumes mender and dresser for Thomas Betterton’s theater company in London as she watches Ned Kyneston every night as he portrays Desdemona in Othello. Mrs. Hughes develops an admiration not only for his performance and skills but also forms romantic feelings for him. However, Mrs. Hughes isn’t content to keep watching Kyneston from the wings, and sneaks off after work to perform as Desdemona illegally at the Cockpit Tavern to packed houses. When Kyneston finds out, he is livid.

Kyneston constantly belittles, ignores, and underestimates Hughes through this film and is supremely arrogant to everyone, enjoying the notoriety he’s achieved as the premier female impersonator in London. However, after he offends King Charles (played by Rupert Everett), and his mistress, Nell Gwynn, (herself an aspiring actress), the King in retaliation, bans men from playing women, thereby making Kyneston seem like a degenerate, incapable of getting work. He sinks into alcoholism and depression, but finds comfort when Hughes finds him and nurses him back to health. The two then form a romantic bond.

In the third act twist of the movie, the actress playing Desdemona in Mr. Betterton’s theater is pregnant, so Margaret must take over her role. Kyneston sees an opportunity to regain respectability as an actor, so he demands to be given the role of Othello. In my favorite scene of the film, Kyneston rehearses the death scene of Othello, changing the acting style from over-the-top stylistic 17th century to very modern naturalistic portrayal:

The two actors perform a fantastic modern naturalistic portrayal of Othello before the king, and they both become respected actors who learn to respect each other.

Danes performs with wonderful real pathos as Hughes and Desdemona. In fact, all the performances are great, the the writing is top notch, and as I said the costumes and cinematography are phenomenal. It’s a very fun, slightly naughty romp through Restoration England, not unlike the flirtatious comedies of Behn and Wycherly.

Special merit goes to Billy Crudup, who had to completely transform his voice, gestures, and dialect for the film. He worked closely with a dialect coach, a physical acting coach, and the director Richard Eyre, who has worked in theater for over 20 years, and has a lot of experience with Shakespeare:

The film is not without flaws; there are some plot elements that are a bit dated and a bit unsettling. While it is true that the real Ned Kyneston was rumored to have relationships with both men and women, including famously, George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, who appears in the movie. Kyneston’s sexual identity is constantly shifting through the course of the movie, and it’s not handled very delicately. In the beginning of the film, Ned seems very firmly homosexual; his relationship with the Duke of Buckingham is played fairly respectfully, though Ned himself is hardly a positive portrayal of a gay or bisexualim man.

Even worse, when Buckingham rejects him, Crudup’s Kyneston seems to be coaxed by Hughes to become heterosexual, which he remains through the course of the movie. Now these actors have fantastic chemistry together, but it seems bizarre that Kyneston is all of a sudden changing his sexual identity at the same time he’s changing his style of performance. That doesn’t seem genuine, (at least in my experience), and it might be offensive to members of the LGBTQ community to assume that a man might think he’s one identity and then choose to be a heterosexual.

Historical Details that the movie gets right:

1 it is true that for hundreds of years it was considered socially unacceptable for women to play parts on the London stage although it was common practice in Italy and France and other countries

2. Ned Kynaston, Thomas Betterton, and of course Mrs. Hughes are real people who performed during the Restoration. However, they actually rarely worked together. Much like the Admiral’s Men and Chamberlain’s men in Shakespeare In Love, The Duke’s Company which is where Betterton worked, while Mrs. Hughed mainly performed in the rival King’s Company.

Sources:

1. Katarzyna Bronk- No Press is Bad Press-Being an Actress in English Restoration. Stardom: Discussions on Fame and Celebrity Culture, 23-34, 2012. Retrieved online from: =related:YvjGsAEzxIoJ:scholar.google.com/&hl=en&as_sdt=0,39#d=gs_qabs&u=%23p%3DYvjGsAEzxIoJ