For Shakespeare’s Birthday, I thought I would discuss his most famous speech what is arguably his greatest play. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark was written in 1600, the pinnacle/ middle of Shakespeare’s career, after Julius Caesar but before Macbeth.

To Be Or Not To Be has intrigued and mystified people for centuries. It is full of ambiguous imagery, haunting images, and solemn contemplative ideas. I’m going to try and break the speech down first like an intellectual argument, but I will also give you some of my interpretation of Hamlet’s thoughts and feelings. Shakespeare’s genius is creating a speech that gives plenty for the reader to interpret,, but it’s up to the reader to decide what’s happening in the speech.

Just a refresher of the plot:

1. The king has died and been seen as a ghost

2. He tells his son Hamlet that he was murdered by his brother Claudius, who killed him to become king and marry Hamlets mother, Gertrude.

Hamlet is trying to determine if the ghost is telling the truth and if so, how can Hamlet revenge the death of his father?

The speech occurs right in the middle of the play. Hamlet has been acting strange and the king is worried. He hides behind a tapestry right before Hamlet enters. He then delivers this famous and highly cryptic speech:

Ham. To be, or not to be, that is the Question:

Whether 'tis Nobler in the minde to suffer

The Slings and Arrowes of outragious Fortune,

Or to take Armes against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them: to dye, to sleepe

No more; and by a sleepe, to say we end

The Heart-ake, and the thousand Naturall shockes

That Flesh is heyre too? 'Tis a consummation

Deuoutly to be wish'd. To dye to sleepe,

To sleepe, perchance to Dreame; I, there's the rub,

For in that sleepe of death, what dreames may come,

When we haue shufflel'd off this mortall coile,

Must giue vs pawse. There's the respect

That makes Calamity of so long life:

For who would beare the Whips and Scornes of time,

The Oppressors wrong, the poore mans Contumely,

The pangs of dispriz'd Loue, the Lawes delay,

The insolence of Office, and the Spurnes

That patient merit of the vnworthy takes,

When he himselfe might his Quietus make

With a bare Bodkin? Who would these Fardles beare

To grunt and sweat vnder a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The vndiscouered Countrey, from whose Borne

No Traueller returnes, Puzels the will,

And makes vs rather beare those illes we haue,

Then flye to others that we know not of.

Thus Conscience does make Cowards of vs all,

And thus the Natiue hew of Resolution

Is sicklied o're, with the pale cast of Thought,

And enterprizes of great pith and moment,

With this regard their Currants turne away,

And loose the name of Action. Soft you now,

Now before I talk about the context of the speech, I want to deconstruct it as an intellectual argument. Hamlet is grappling with something huge, and he is weighing the consequences of his potential actions. Remember, Hamlet is a prince, but he is also a college student, so he turns his choice into an intellectual argument.

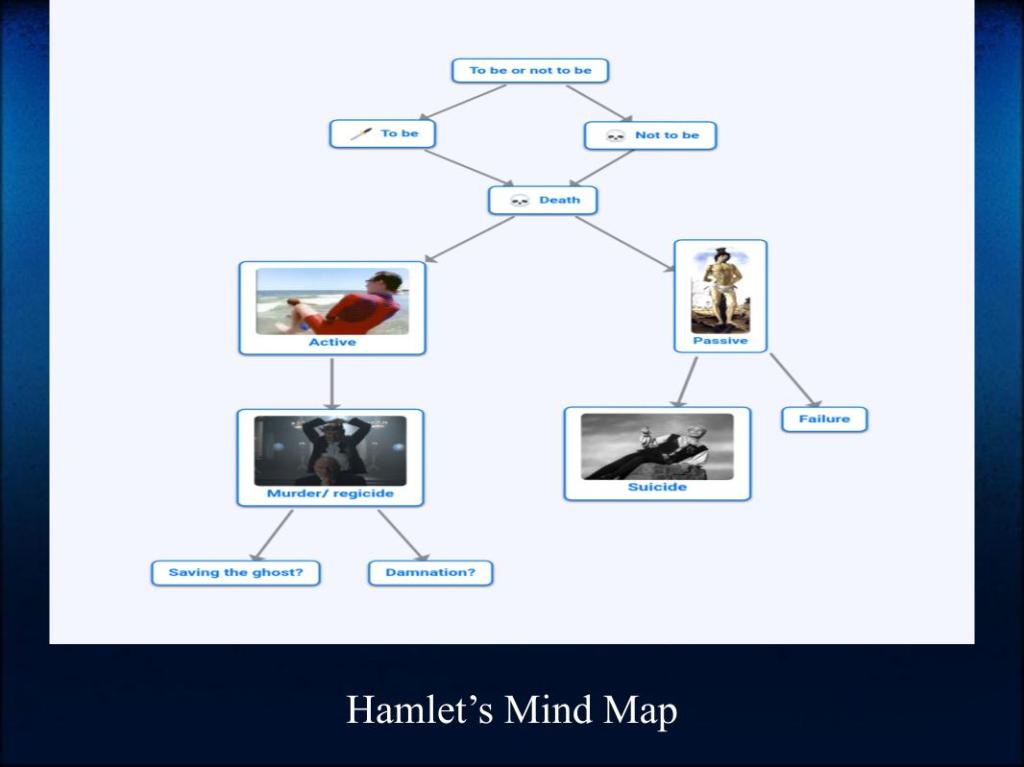

- If you look at the speech as an argument, it hinges on two points- to be or not to be.

- One is passive and one is active

- Both actions are potentially lethal, as evidenced by the two metaphors Hamlet describes later.

Contrary to popular belief, I believe that this speech is not just about suicide. It’s about the choice between suicide and murder, (in this case killing Claudius).

Three Speeches- Macbeth, and Hamlet

Lets discuss the two central images at the start of this speech. One is active- fighting (“taking arms”), and one is passive (“to suffer…”). Both choices have a similar outcome- death. No one can fight the sea, and arrows are just as lethal.

Let’s look at the speech again, and turn it into a series of beats using the conjunctions “and, but, and or,” The speech has 6 beats. What he’s thinking about or feeling is open to interpretation, but the argument definitely changes at these points. First the thesis:

- This beat sets up the two options (murder and suicide). Why do I think this? Because it’s similar to two other speeches: https://youtu.be/nq3hcs1yFKw

It’s worth noting that about the same time, Shakespeare wrote three great soliloquis; Hamlet’s “To Be Or Not To Be,” Macbeth’s “If It Were Done,” and Brutus’ “It must be by his death.” All three speeches have some notable commonalities:

- All three speeches are in passive voice; the would be murderer wishes he didn’t have to kill someone, but wants the victim dead nonetheless.

- Refuse to mention the name of the man who will die.

- Refuse to say ‘murder’

- Personify death in abstract terms.

When I noticed the commonalities between the speeches, I came to realize that all of them are about murder, not just suicide. I think Hamlet alone contemplates suicide as well as murder, possibly because unlike Brutus and Macbeth, Hamlet is not at all sure he’s doing the right thing.

Beat 1 The Nerve: Hamlet is working himself up for something; either murder or suicide. It’s ambiguous which one he starts with, and largely depends upon the actor’s interpretation.

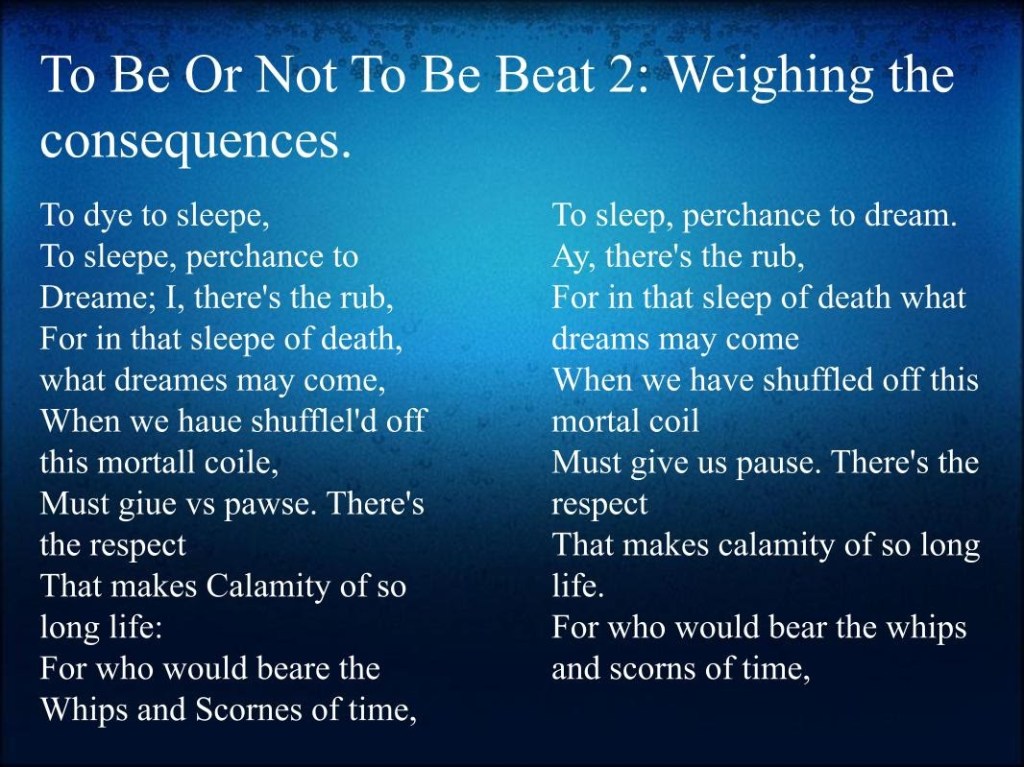

Beat 2 The Consequences

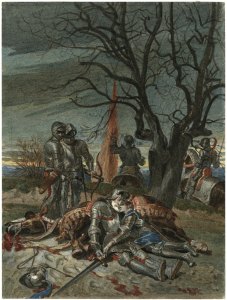

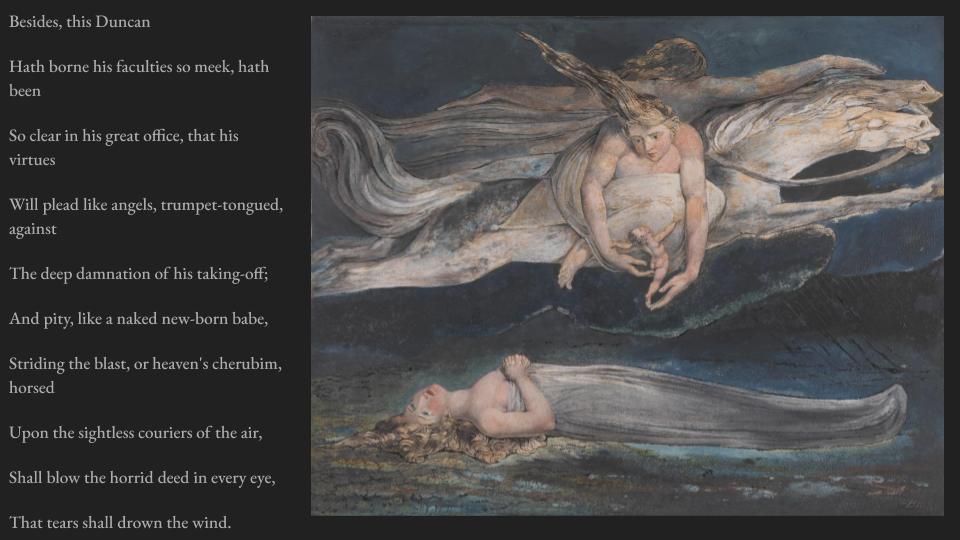

Whether Hamlet kills the king or himself, either way he could die and when he does, his soul will have to answer for his actions. This is similar to Macbeth, who worries that his foul murder will be exposed and judged by “Heaven’s cherubim, horses upon the sightless couriers of the air.”

“There’s the rub”- there’s the catch.

“Coil” refers to a snake skin. The line characterizes death as shedding an earthly body, something that seems all too easy to do. It’s an uncomfortable image because it makes death look all too easy. It also calls to mind the story of Gilgamesh, who had a flower that would grant him immortality, but a snake stole it, which is why snakes cam shed their skin, seemingly growing young again forever.

Beat 3: Smothering In Surmise: https://youtu.be/gFG91lXgNcs

This beat is where Hamlet seems smothered in his frustrations with life.. Rather than making a decision, he’s sidetracked with a laundry list of universal problems. His energy seems up, but it’s unclear why.

When I performed this portion of the speech, I realized that everything Hamlet refers to, Claudius has done: he has oppressed and wronged the kingdom, he has delayed the law, and he has hindered Hamlet’s love for Ophelia by letting Polonius deny Hamlet’s access to her. Perhaps the laundry list is designed to psych him up- listing all the reasons Claudius deserves to die, (without tipping him off).

Beat 4: The Downward Spiral

Once again Hamlet is thwarted by the concept of Death and divine judgment. He seems to imply that everyone is scared into compliance with the threat of death.

The Conclusion:

Hamlet’s conclusion is that he has no conclusion. He can’t kill himself because his conscience tells him that God is against it, and he cannot kill Claudius because of fear of death or damnation.

When he says “The native hue of resolution,” he means red, (as in blood), is curtailed, cut off by the very thought of Deaths pale scythe.

Interpretations:

Mel Gibson plays Hamlet as a sort of man in mourning. He is as close to the action movie hero as Hamlet gets with his large, imposing physique and brutal looking medieval sword:

Speaking of action heroes, the whole movie Last Action Hero has a reoccurring motif of nodding to Hamlet. The avenging hero archetype is the prototype for every action movie, every superhero, (and most kung fu), and it began with Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This is why it’s hilarious that Schwarzeneger portrays him in Last Action Hero- the movie is a loving parody of every single action star since the original- Hamlet.

Why Else might Hamlet be so cryptic?

Not all versions are about suicide or murder

Lawrence Olivier believed that Hamlet has an Oedipus complex, and therefore has an unconscious desire to murder his father and sleep with this mother, which is why he considered himself unworthy to avenge his father’s death. In Olivier’s To Be, you can almost see his Hamlet aroused by his own Oedipal fantasies and then recoiling with disgust right before he says the line: “Perchance to dream.”

Kenneth Branaugh’s Hamlet centers around court intrigue. In contrast with Oliver’s Gothic Elsinore, his is bright and baroque, but it’s full of two way mirrors. Half the film is either large shots with lots of people watching public performances or POV shots of people being watched.

Branaugh’s interpretation of “To Be,” focuses on the possibility that Hamlet knows that Claudius is watching him through the two way mirror- he frightens him, puzzles, him, but in the end, never gives Claudius a clue as to his true intentions.

Murder or suicide?

the speech is not only famous for its universality but its evocative imagery, clear (albeit cryptic) construction, and heightened circumstances.

Shakespeare is able to give us a complete character without giving everything away, which allows anyone to reinterpret the character their own way. That is why Shakespeare’s characters endure.