In doing my research for Twelfth Night, I came across a fantastic production from Shakespeare’s Globe in 2002. It used what is known as “original practices,” meaning that the actors tried to replicate everything we know about the way Shakespeare’s actors performed.

The play was performed in the great Globe Theater, which is itself a replica of Shakespeare’s original playhouse, which means that it was outdoors, using mostly natural lighting, and minimal sets. https://youtu.be/qtoUeVjP_rs

In addition, all the women’s roles were played by men, and the actors played multiple parts, which were all accurate stage practices from Shakespeare’s era. Most exciting of all, the actors all wore authentic 17th century costumes designed by veteran costume designer, Jenny Tiramani:

/https://prezi.com/m/zef_cpurcfsl/jenny-tiramani/

Few things determine how an actor moves or looks more than the clothes he or she wears, and watching these actors wear doublet and hose and real Jacobean dresses really fires up my imagine and makes me feel that I’ve truly been transported through time. The production is available on DVD, as well as several clips on YouTube, and I urge you to take a look at it. In the meantime, I’d like to comment a little on how the costumes from this production inform the audience about the characters that wear them.

Some Info On 17th century fashion

* Men

- Tight pants or hose, and stockings designed to show off the legs

- Tight jackets made of wool or leather called doublets

- By the 17th century, starched ruffs were being replaced with lace collars.

- Starched collars called ruffs around the neck.

* Women

Longer skirts, often embroidered with elaborate patterns

* Servants- Servants like Cesario (who is actually the Duke’s daughter Viola in disguise), would typically wear matching uniforms called liveries, a sign of who they worked for and their master’s trust in their abilities. People judged the aristocracy by how well they trained and controlled their servants, so wearing your master’s livery meant he trusted you to represent his house.

In her first scene as Cesario, a servant named Curio remarks to her that Orsino has shown favor to “him” from the very beginning. This might explain the rich garments that Viola wears in this production, which resemble a noble gentleman more than a servant.

In her first scene as Cesario, a servant named Curio remarks to her that Orsino has shown favor to “him” from the very beginning. This might explain the rich garments that Viola wears in this production, which resemble a noble gentleman more than a servant.

A higher ranking servant like Malvolio would be able to wear a higher status garment, which is why you see Steven Fry as Malvolio dressed in a handsome doublet.

A higher ranking servant like Malvolio would be able to wear a higher status garment, which is why you see Steven Fry as Malvolio dressed in a handsome doublet.

3. Character notes:

* What are they wearing?

* Why are they wearing it?

* How do the clothes inform the movement?

1. Viola (Eddie Redmane)  Viola, the star of the show, begins the show as the daughter of a duke, who has just been shipwrecked in a foreign country, so her clothes must look bedraggled and worn, yet appropriate to her status. As I said before though, for the majority of the play, Viola is disguised as the servant Cesario

Viola, the star of the show, begins the show as the daughter of a duke, who has just been shipwrecked in a foreign country, so her clothes must look bedraggled and worn, yet appropriate to her status. As I said before though, for the majority of the play, Viola is disguised as the servant Cesario

2. Malvolio (Steven Fry)

- Malvolio wears dark colors since he’s a Puritanical servant.

- He mentions that he has a watch. The first ever wristwatches ever came into being around this time.

- Most productions give Malvolio a Gold chain and/ or a staff of office to show his status, and his prideful nature.

- In Act III, Malvolio is tricked into wearing yellow stockings with cross garters.

3. Maria the Countess Olivia’s maid, (who has an appetite for tricks and pranks), Maria’s job is to dress and help Olivia with her daily routine. This might include tying up her corset, putting on her makeup, and helping her with the elaborate gowns that nobles wore during this period. In the video below, you can watch a dresser help get an actress into an elaborate costume for another Globe theatre production. Just think of the amount of time and hard work it would take for a servant like Maria to dress Olivia every day!

In the play, Viola momentarily mistakes Maria for her mistress because she wears a veil. This also suggests that, rather than wearing a livery like Cesario, maybe Olivia let Maria wear some of her older clothes, which was a common practice for high level servants. A lot of the costumes Shakespeare’s company wore were probably hand me downs from their aristocratic patrons.

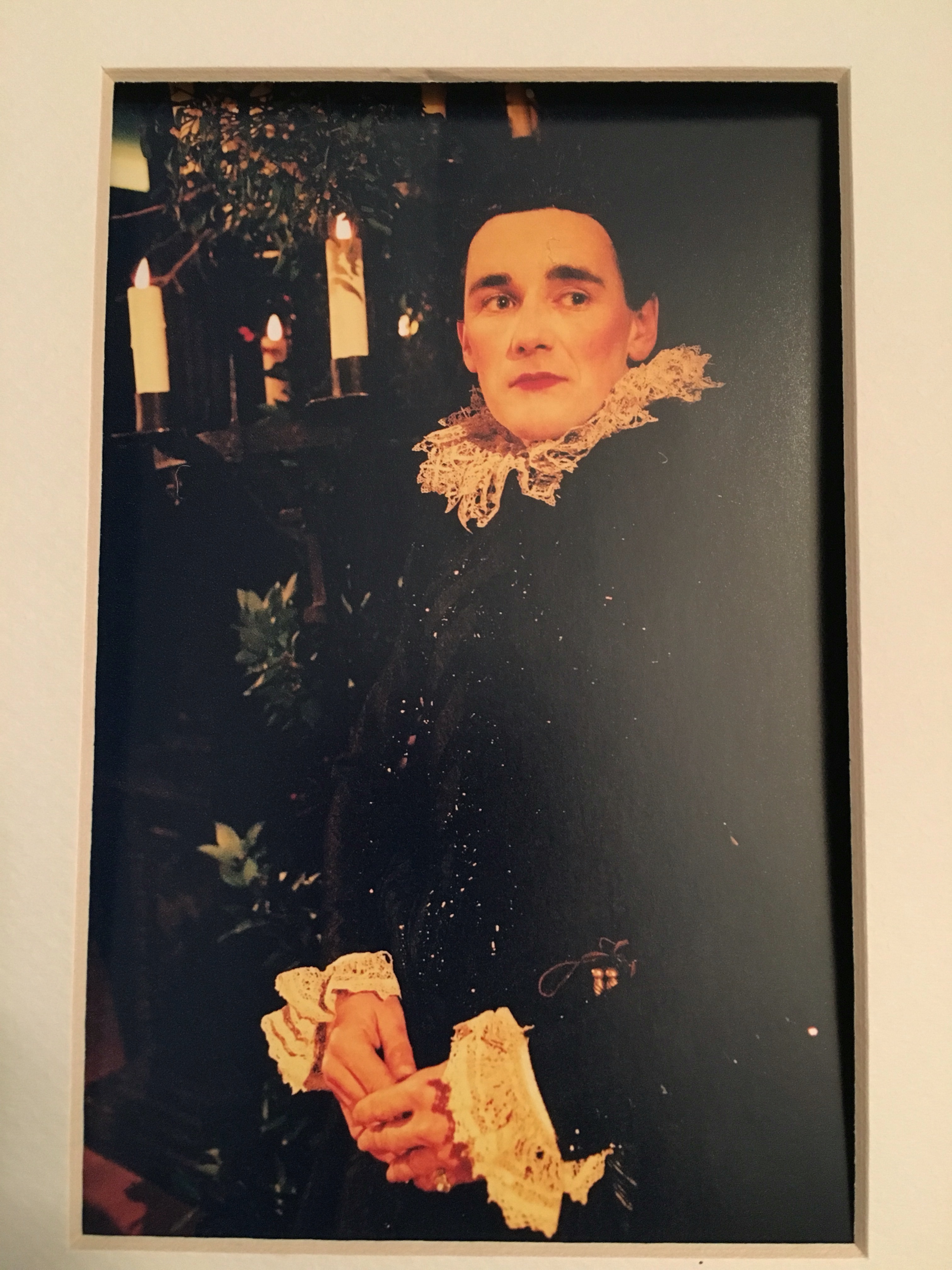

4. Olivia (Mark Rylance)

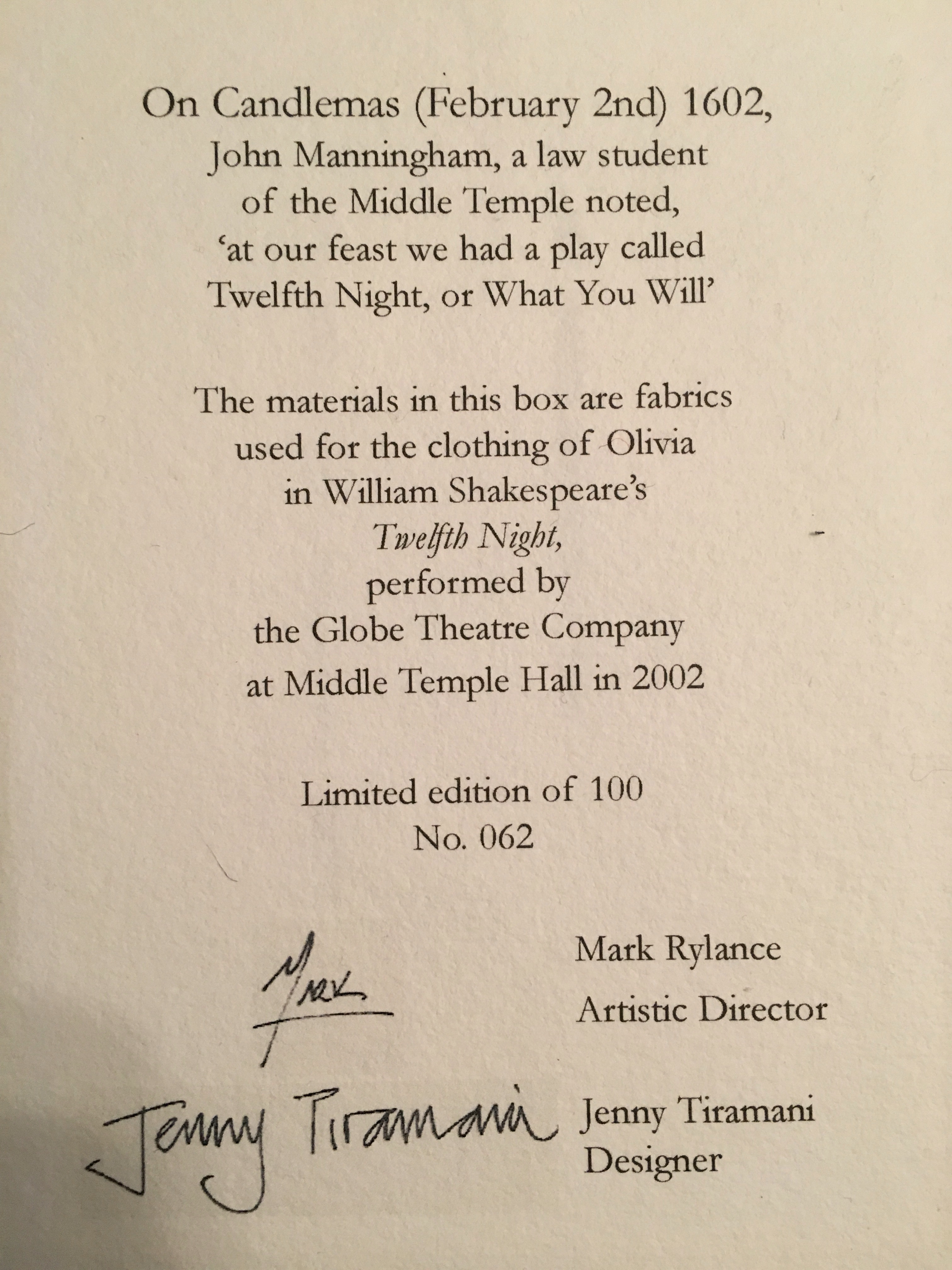

In this production, the countess and all the female roles were performed by men, just as they were in Shakespeare’s Day. Mark Rylance, who played Olivia, was also the Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre.

- Olivia is mourning her lost brother, which is why she’s traditionally dressed in a black dress and veil

- The dress is black silk with elaborate embroidery, as you can see from this actual sampler of the real fabric used in the show. You will also notice the threads holding the fabric together with metal points at the end. Olivia’s gown was hand sewn into many different pieces and tied together with these points. One nickname Shakespeare gave servants like Maria was “One who ties [her] points.”

- The dress is large and has a long train, making it hard for the actor to move: https://youtu.be/dcSNTspXGYk

Costumes like these offer a tantalizing glimpse into history. Just as Shakespeare’s words help an actor bring to life the thoughts and feelings of his age, The type of clothes his company wore helps the actor embody the moiré’s and desires of Shakespeare’s society, whether a mournful countess, a dazzling gentleman, or a reserved Puritan.

References

Feldman, Adam

“Q&A: Mark Rylance on Shakespeare, Twelfth Night and Richard III” Time Out Magazine. Posted: Tuesday November 12 2013

Retrieved online from https://www.timeout.com/newyork/theater/q-a-mark-rylance-on-shakespeare-twelfth-night-and-richard-iii

Minton, Eric. Twelfth Night: What Achieved Greatness was Born Great.

Posted May 22, 2014 to http://shakespeareances.com/willpower/onscreen/12th_Night-Globe13.html.

If you liked this post, please consider signing up for my online course “Christmas For Shakespeare,” which will talk about the costumes, characters, and themes of Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night, as well as Christmas traditions from Shakespeare’s day: https://outschool.com/classes/what-was-christmas-like-for-william-shakespeare-BwVLyBPp?sectionUid=75ee7895-c8ac-437c-9ef7-05cf8e3bf114&usid=MaRDyJ13&signup=true&utm_campaign=share_activity_link

![Candleglow%20PR%20small[1]](https://shakespeareanstudent.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/candleglow20pr20small1.jpg)