I’m delighted to share with you my recommendations for the best Hamlets committed to film! I was pretty strict with my criteria which left a few Hamlets out, so if I missed yours, let me know in the comments.

In order to make this list:

- I have to have seen the whole thing. Sadly that excludes a lot of unfilmed productions or films I haven’t got around to seeing.

- The interpretation has to take a unique stance on the play.

- The actor has to have a clear grasp of the part.

- I personally have to like it. This is subjective, and I will make it clear if something is my opinion, or if I think this interpretation works for classes or private viewing.

By the way, if you’re a teacher, I’ll be sure to mention which productions work for classes, and which, for whatever reason, do not. I also can recommend Common Sense Media to give you a good idea what age group this film works best for:

So, without any further adieu (get it?):

The Good Hamlets

#10: Arnold SChwarzenegger in “Last Action Hero”

I would love to do a full review of this movie. When it works, it is actually a thoughtful deconstruction of the action movie genre, and as this clip shows, the movie concedes that Hamlet was actually the first great action hero. Schwarzenegger is really funny as an action movie parody of “Hamlet,” and everything he does is pretty cathartic for bored school boys who have to read the play in class. Plus, as a funny easter egg, the teacher in the scene who is showing Olivier’s Hamlet on the screen is played by Joan Plowright, who played Gertrude IN THAT FILM, and was married to Olivier in real life!

#9: Bart Simpson in “Tales from the Public Domain”

It’s absolutely astonishing how many Shakespeare easter eggs are in this little episode! How they make fun of medieval history, (the Danes were in fact Vikings in the early middle ages), Elizabethan theater, (when Bart does a soliloquy and is surprised that Claudius can hear him), and the way they compress Shakespeare’s longest play into a five minute episode is masterful satire.

In addition, the cast is perfectly chosen among the Simpsons’ core cast. Long-time viewers know that Moe has wanted to sleep with Homer’s wife for years, so making him Claudius is a brilliant choice. Plus, Dan Castellaneta steals the show with his over-the-top performance as the ghost, which actually reminds me of a 1589 review of Hamlet by Thomas Lodge:

“[He] walks for the most part in black under cover of gravity, and looks as pale as the vizard [mask] of the ghost who cried so miserably at the Theatre like an oyster-wife, Hamlet, revenge!”

THOMAS NASHE, “PREFACE” TO ROBERT GREENE, MENAPHON, (1589)

In any case, this clip is a great way to introduce anyone to Hamlet and I highly recommend it.

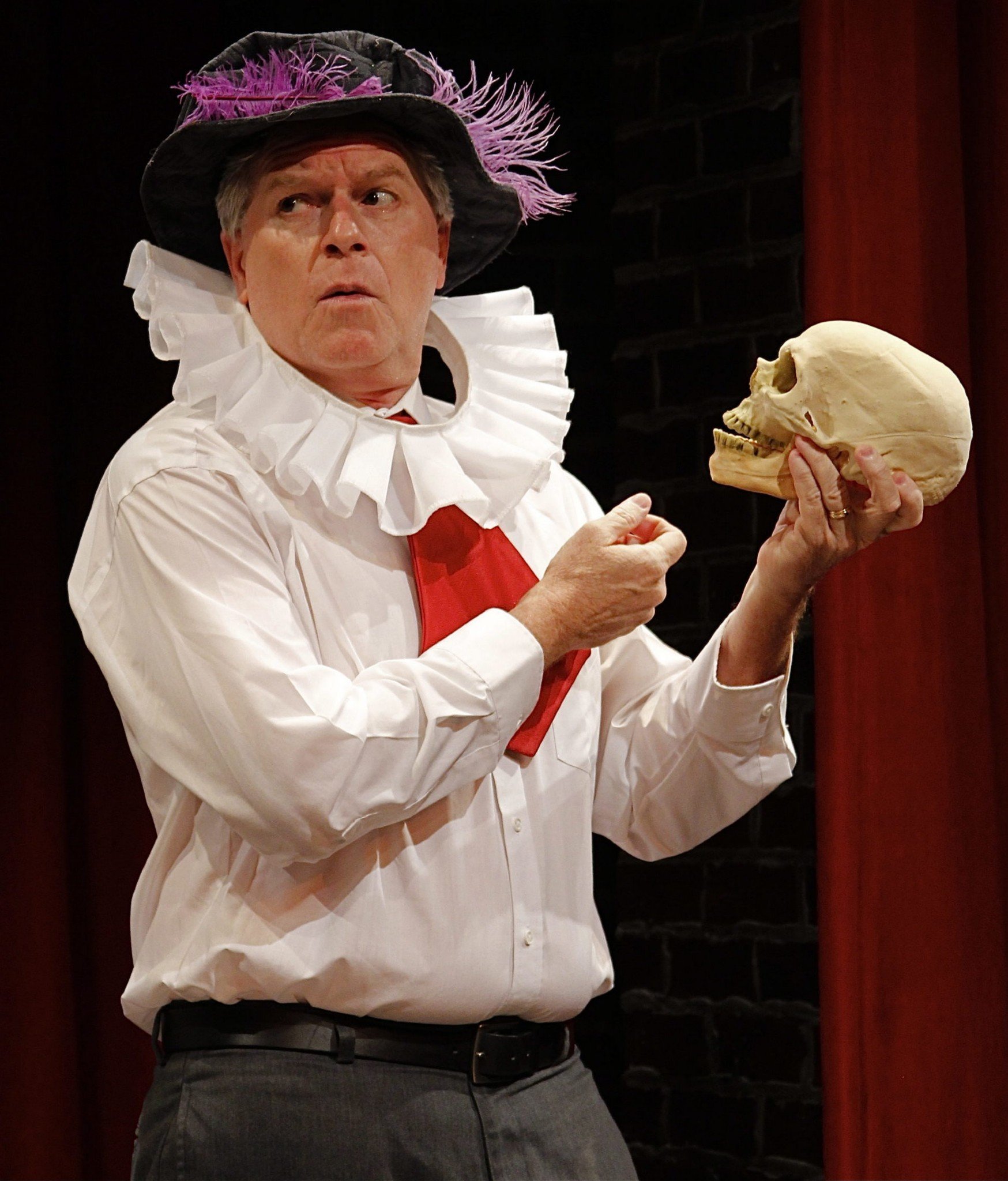

#8: Austin Tichenor in “The Complete Works of Shakespeare- Abridged”

This show is very special to me- in around 1997 my parents went to England and brought home a copy of The Complete Works of Shakespeare (Abridged). I’d only read “Romeo and Juliet” previously and through this show, I gained an appreciation for all of Shakespeare’s plays. Seeing the plays through parody made them seem less lofty and stuffy, and made me want to see and read the original works. This is especially true for “Hamlet,” which occupies the second half of the show, where Hamlet is portrayed by Austin Tichenor.

Tichenor wins my award for “Hammiest Hamlet,” which is just delightful to watch. He clearly takes the part WAAAY too seriously, as evidenced by how emphatically he demands solemn silence from the audience while he attempts to do “To Be Or Not To Be.” Tichenor also serves as the pedantic straight man who tries to keep the show moving and academic, while mediating between his bickering co-stars Adam and Reed. This wonderful Three-stooges dynamic makes every minute of the show fun and frenetic. However, the cast makes it very clear that they are making fun of Shakespeare with love; they never mock the play, they inform as well as entertain, and occasionally they even move the audience as Adam does at the end. In short, this show helped me form my approach to Shakespeare, and it’s largely through Tichenor that I read Hamlet at all, so he’s to blame for this website.

#7: Richard Burton, 1964 (stage production directed by John Gielgud).

With the advent of TV and film making theater seem obsolete, directors knew they had to do something drastic in order to get people to come to the playhouses. Enter John Gielgud, one of the greatest Hamlets of the early 20th century, who directed Richard Burton in a highly-acclaimed production with minimum sets and with actors wearing rehearsal clothes. The idea was to let Shakespeare’s words and the actors’ performances be the focus, and save spectacle for film and TV. This approach has been adopted by many theater companies since, including a few I’ve been a pat of.

Burton has a lot of energy and manic physicality in his portrayal and it makes his Hamlet engaging to watch. Plus Gielgud himself as the ghost is almost operatic to hear. I highly recommend any theater fan to watch it, though it might not translate in a classroom much.

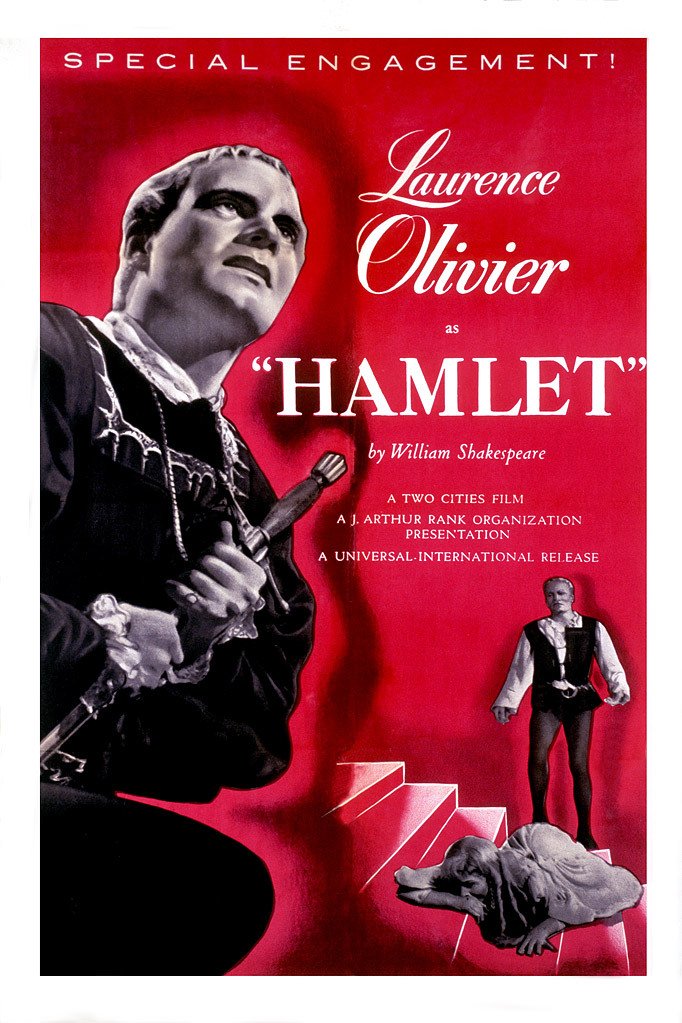

# 6: Laurence Olivier, (Film 1948)

I have my issues with Olivier as an actor and apparently I’m not alone:

I find Olivier’s acting over-the-top, lacking in emotion and subtlety, and I think his directing is generally self-centered. He rarely deigns to give close-ups to anyone but himself and a lot of the scenes he directs are filmed like stage plays. That said, Olivier’s Hamlet is really good. SIr Laurence talked to Ernest Jones about the theory that Hamlet might have had an Oedipus Complex and created a unique and well-thought-out interpretation for his Hamlet. First off, casting his real-life wife Joan Plowright as Gertrude, fills the Closet scene with uncomfortable tension. He also did a great job making the ghost seem as imposing and accusatory as possible, as well as making Claudius as disgusting as possible.

You get the idea that this film is how Hamlet sees the world with its dark and shadowy towers, representing Hamlet’s melancholic mind, his imprisoned spirit, and his dark desires. Also as many people have pointed out, Gertrude’s bed chamber looks like a female organ, making the Oedipus theory even more explicit.

Even I have to admit that Olivier nailed the “To Be Or Not To Be,” Speech. He squirms at his own Oedipal fantasies, and contemplates jumping off the battlements in a captivating and subtle way. The performance and cinematography is iconic, and it makes me grudgingly admit Olivier, for all his faults, is still one of the best Hamlets of all time.

I would recommend this film to every Shakespeare film fan and any hardcore Shakespeare scholars. I would caution against showing the whole thing in a class however, since it’s black and white, and again, I find Oliver’s delivery very old-fashioned.

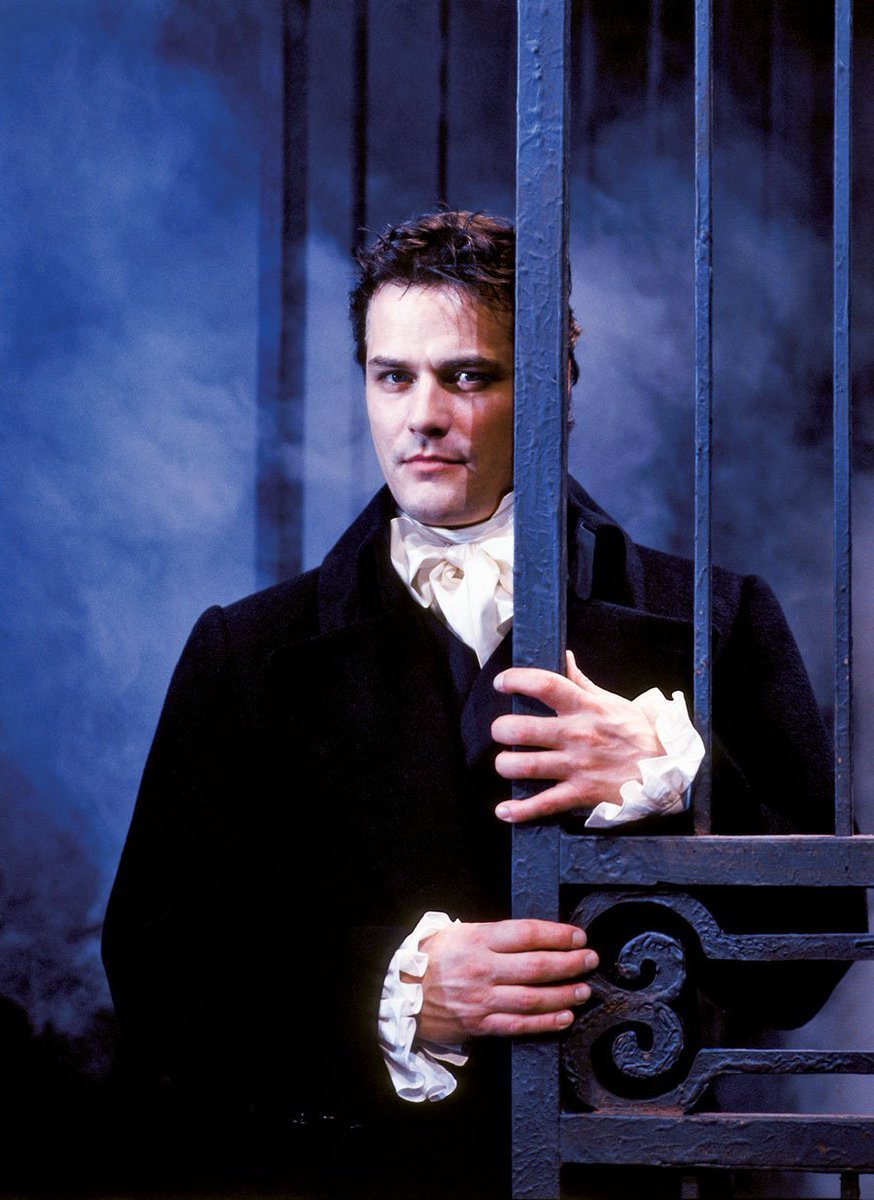

#5: Paul Gross, (StratforD Festival, 2000)

Thus far, I’ve mainly reviewed British and American Hamlets. Paul Gross is one of Canada’s most celebrated actors who gained fame as one of the best Hamlets at Toronto’s Stratford Festival. Unlike most Hamlets who go for the humanistic prince version of Hamlet, Gross plays him with sort of an animal intensity, like a wounded bear who will growl at you if you get in his way.

I have to admit I broke my own rule with this one- I haven’t really seen Gross’ portrayal, but I believe I saw it well-represented in his role as Geoffery Tennent, the Shakespearean Actor-turned madman-turned director in the Canadian TV show “Slings and Arrows.” This amazing dark comedy portrays the ins and outs of a Shakespeare Company from the normal problems of mounting a play to backstage drama, even the funding and marketing gets focus! Basically, the show is The Office for Shakespeare nerds, except for one ghostly cast member (no spoilers).

4. Benedick Cumberbatch / John Harrell

I couldn’t make up my mind between these two Hamlets, so I’m listing them together (guess that makes me Hamlet too). One is one of the most accomplished Shakespearean actor in recent memory, an RSC alumn, and a Hollywood star to boot, Benedick Cumberbatch.

Both these actors have similar strengths- they’re both tall and imposing with aquiline features. They are also highly physical performers. I talked in my lecture on Richard III about how Harrell performed the role of Gloucester with his legs tied together and a bowling ball strapped to his hand. Appearance-wise- Harrell and Cumberbatch are so similar, that it’s actually a joke at the ASC that they must be long-lost twins.

That said, when it comes to their approach to Hamlet, these two actors couldn’t be more different. Cumberbatch focused on Hamlet’s emotional turmoil- he was tortured and angry, full of youthful angst and volatility. This particular production is sort of an anachronistic mash-up of modern and period, which gives it a sort of dream-like quality that I really enjoy. Like Richard Burton, the director knows how to stage a play differently from a movie or TV show, which is especially important with this actor, since we can see him on all those platforms.

Nor should they have. Full of scenic spectacle and conceptual tweaks and quirks, this “Hamlet” is never boring. It is also never emotionally moving — except on those occasions when Mr. Cumberbatch’s Hamlet is alone with his thoughts, trying to make sense of a loud, importunate world that demands so much of him.

By Ben Brantley

New York Times, Aug. 25, 2015

John Harrell on the other hand is a more mature and subtle Hamlet, more interested in saving his hide than contemplating his navel. This Hamlet masks pain with humor and sardonic wit and it translates to all his relationships with the King, Queen, and courtiers.

Rather than a sour, dour, morose, obtuse, naval-gazing Hamlet, this prince was cunning, cynical, devious, sarcastic, and very much enjoying his feigned madness, his chess game with the king, and his fencing bout with Laertes.

Eric Minton

https://www.shakespeareances.com/willpower/onstage/Hamlet-11-ASC11.html

#3: Papaa Essiedu, Royal Shakespeare company

OK, I have to admit that I didn’t see this whole production either, but it’s so cool and the acting is so good I wish I had! Papaa Essiedu is an electrifying blend of wit, sadness, manic excitement, and rage. His fresh take on a role that can be rather dour is why even the little I’ve seen of his performance makes it one of my favorites!

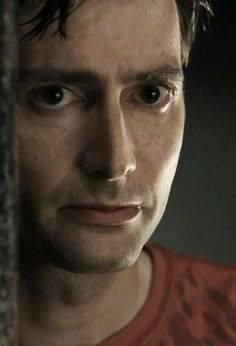

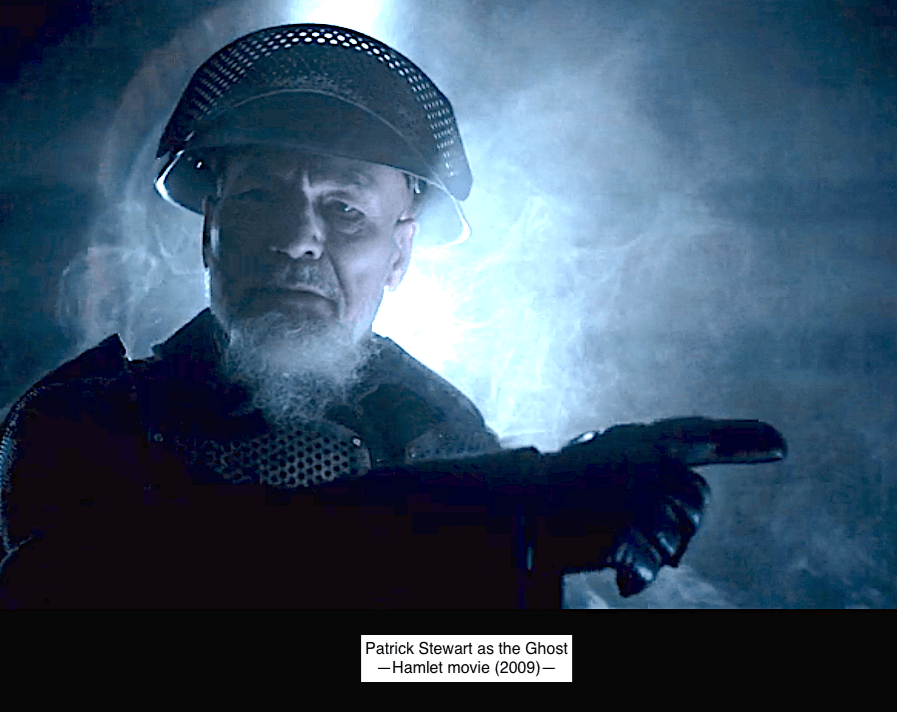

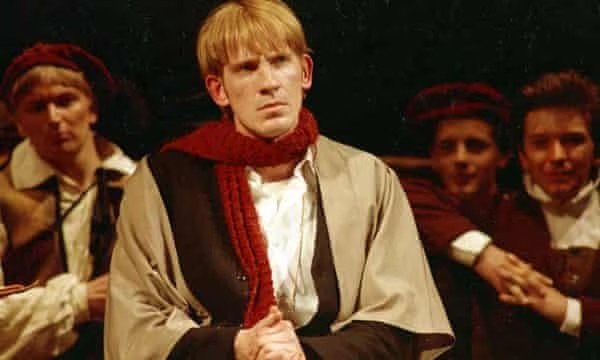

#2: David Tennet, RSC 2009

Tennet does an incredible job of encapsulating Hamlet’s quick wit, giddy excitement, frailty, fury, and frustration, especially with himself. I love the fact that he does “To Be Or Not To Be” in a superhero T-Shirt. In a way, this Hamlet is constantly wishing he was more of the action-movie type that Schwartzenegger parodies at the top of this list. Like Harrell, Tennent’s Hamlet masks his pain with humor, but you can see him struggle with it and try to pull himself out of despair. All these Hamlets find a way to nail at least one aspect of the character, but Tennet in his short 3 hours on the stage, manages to highlight all of them.

I recommend this version for any viewer in any classroom. It’s beautifully shot, extremely well acted, fast-paced, funny, and exciting. I cannot recommend it highly enough.

Honorable mentions: Anton Lester, Ian McKellen, MiChelle Terry, and Sir John Gielgud

I haven’t seen any of these Hamlets and have been unable to locate any clips, but I have the deepest respect for all of these actors, so I thought I’d highlight them here.

I’d also like to give special mention to Michelle Terry. Gender-blind productions of Shakespeare get a lot of flack that is undeserved, and there’s nothing wrong with a female Hamlet. To quote Geoffrey Tennet in Slings and Arrows: “Shakespeare didn’t care about anachronism, and neither should we.”

I didn’t include Ms. Terry in this list, simply because I wasn’t able to get to the Globe, and I wanted to focus on productions that people can watch for free. If you wish, you can watch her 2018 performance on the Globe Theater’s steaming website:

https://player.shakespearesglobe.com/productions/hamlet-2018/

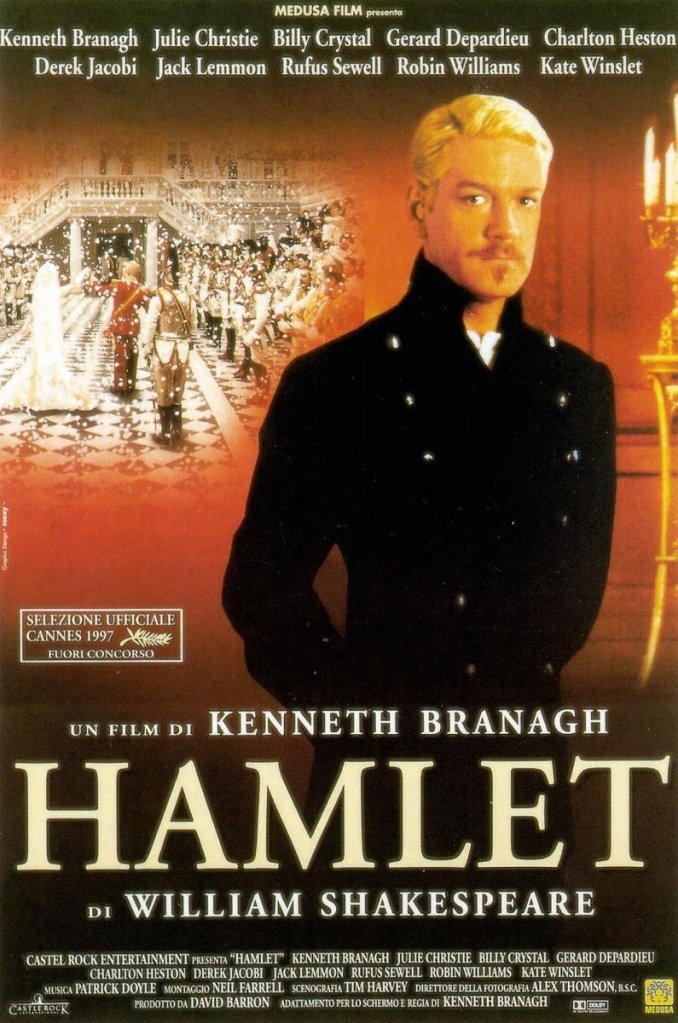

#1: Kenneth Branaugh

You probably saw this coming. I’ve made it clear in other posts that I absolutely love Branaugh’s Hamlet, after all his film was one of the first Shakespeare movies I ever saw and the first one I really enjoyed. I discuss in detail why I love this movie the best in my review of the film, but to summarize, I think the direction is incredible, the music is excellent, the cast is nearly perfect, and Branaugh himself puts a huge amount of love, craft, skill, experience, and maybe a little madness into his portrayal of the character. I know Branaugh isn’t everyone’s cup of tea; other Hamlets on this list might be more enjoyable, fun, or subtle, for you. But for me, Branaugh’s will always be my favorite.