New Podcast: “Crafting A Character: Brutus.”

Since Easter and Passover are coming up, (and we are already in the middle of Rhamadan), I thought I’d examine Shakespeare’s depiction of other worlds both celestial and infernal. As the quote above says, philosophers and poets often wonder what greets us in the hereafter, so let me be your guide through Shakespeare’s poetic renderings of heaven and he’ll, accompanied by some gorgeous artwork from HC Selous, William Blake, and others.

Shakespeare was no doubt interested in religion. He quotes from and alludes to the Bible many times in his plays. More importantly, he lived in a time when the national religion changed three times in just 4 years! When Henry VIII changed England to a protestant country, the religious identity of England completely changed:

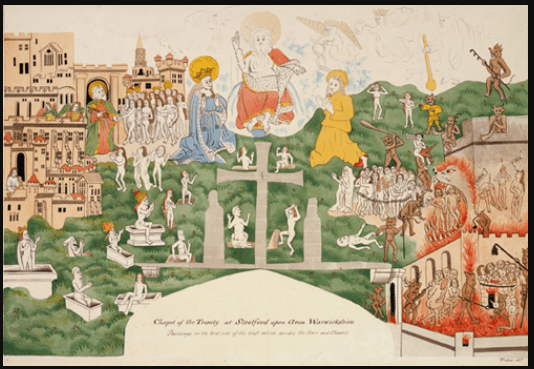

This change was not just felt in monasteries, but in all English churches. King Henry decreed that certain Catholic traditions like Purgatory, indulgences, and praying to saints were idolatrous, and were therefore banned in the Church of England. So, when Shakespeare’s father was called to destroy the “idolatrous” images of the Last Judgement in the Guild Chapel of Stratford’s Holy Trinity Church, he had no choice but to comply. If you click on the link below, you can see a detailed description of the images that Shakespeare no doubt knew well in his family’s church, until his father was forced to literally whitewash them.

Like the images on the Stratford Guild chapel, the ideas of Catholic England didn’t disappear, they were merely hidden from view. Shakespeare refers to these Catholic ideas many times in his plays, especially in Hamlet, a play where a young scholar, who goes to the same school as Martin Luther, is wrestling with the idea of whether the ghost he has seen is a real ghost from purgatory, or a demon from hell, (as protestant churches preached in Shakespeare’s life).

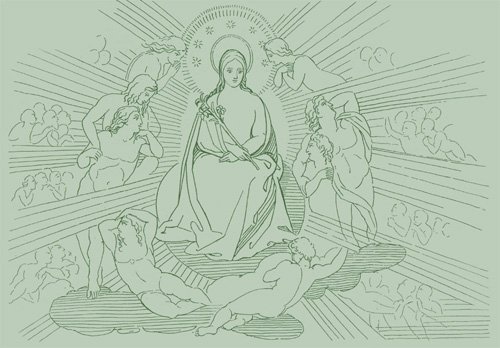

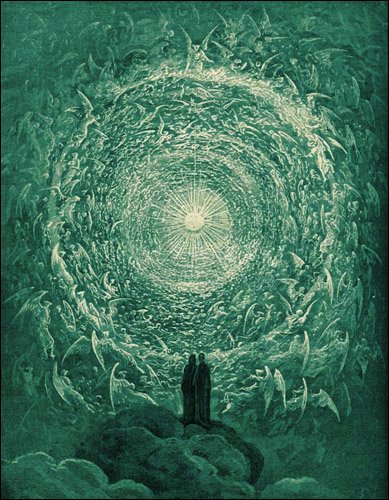

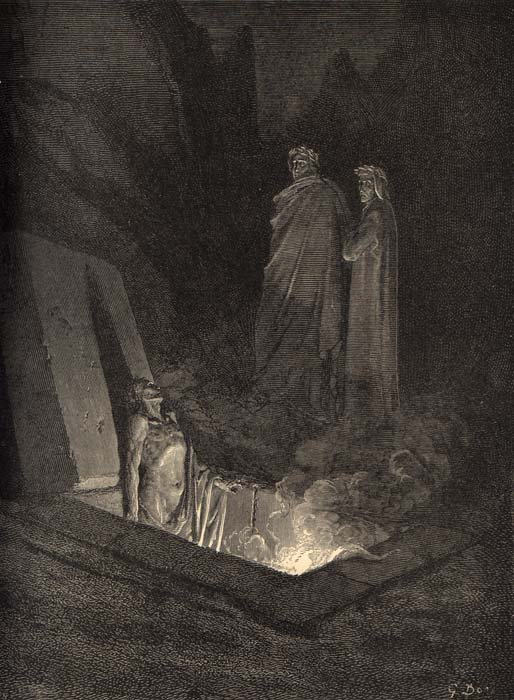

I’ve written before that the ghost of Hamlet’s father teases us with the possibility that he might be a soul in purgatory, the Catholic afterlife realm for those not evil enough for Hell, nor good enough for Heaven. At the height of their powers, monks and bishops sold prayers called indulgences that supposedly allowed a soul’s loved ones to buy them time out of purgatory, thus making them able to ascend to Heaven quicker. The image above is an illustration from Purgatorio, part of Dante’s Divine Comedy, where he visits the soul of

Buonconte da Montefeltro, who is languishing because he doesn’t yet have the strength to get out of purgatory and enter Heaven.

Of course, the Tudor monarchs Henry VIII and Elizabeth I abolished indulgences and proclaimed that purgatory itself didn’t exist, but ideas can’t die, and I feel that Shakespeare was at least inspired by the notion of purgatory, even if he didn’t believe in it himself.

(Horatio) Hamlet, Act I, Scene i.

As a young boy, William Shakespeare was entertained by medieval Mystery plays; amateur theater pieces performed by local artisans that dramatized great stories from the Bible. We know this because he refers to many of the characters in these mystery plays in his own work, especially the villains. King Herod is mentioned in Hamlet and many other plays in and many of Shakespeare’s villains seem to be inspired by the biblical Lucifer, as portrayed in Medieval Mystery Plays.

In this short video of the Yorkshire Mystery play “The Rise and Fall of Lucifer,” we see God (voiced by Sir Patrick Stewart), creating Lucifer as a beautiful angel, who then, dissatisfied with his place in God’s kingdom, is transformed into an ugly devil. At first, Lucifer mourns losing his place in Paradise, but then finds comfort by becomming God’s great antagonist.

Compare this character arc with Shakespeare’s Richard of Gloucester, who also blames his unhappiness on God, (since he feels his disability and deformity are a result of God’s curse). Richard is angry with God, nature, and society, so he wages against them all to become king.

“Then since the heavens hath shaped my body so, let Hell make crook’d my mind to answer it.”

Richard of Gloucester, Henry VI, Part III, Act III, Scene i.

“All is not lost, the unconquerable will, and study of revenge, immortal hate, and the courage never to submit or yield.”

Lucifer― John Milton, Paradise Lost

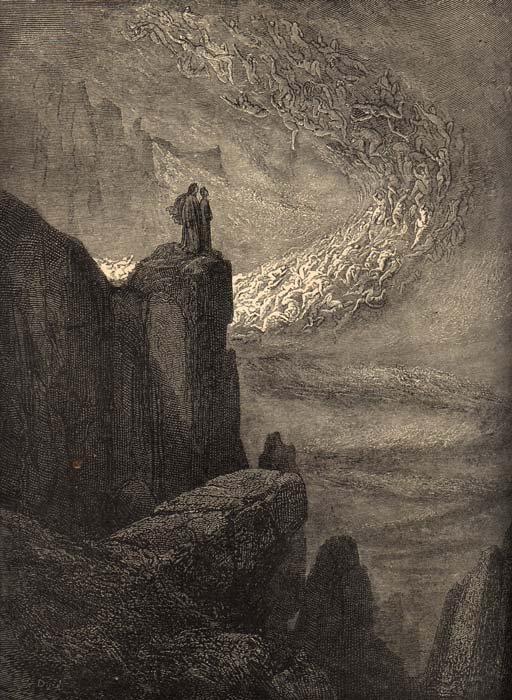

Claudio. Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought Imagine howling: ’tis too horrible!

—Measure For Measure, Act III, Scene i

“Methought I crossed the meloncholy flood with that grim ferryman the poets write of, into the kingdom of perpetual night.”

— Richard III, Act I, Scene iv.

The heavens themselves, the planets and this centre

Observe degree, priority and place,

Insisture, course, proportion, season, form,

Office and custom, in all line of order;

And therefore is the glorious planet Sol

In noble eminence enthroned and sphered

Amidst the other; whose medicinable eye

Corrects the ill aspects of planets evil,

And posts, like the commandment of a king,

Sans cheque to good and bad: but when the planets

In evil mixture to disorder wander,

What plagues and what portents! what mutiny!

What raging of the sea! shaking of earth! Commotion in the winds! frights, changes, horrors,

Divert and crack, rend and deracinate

The unity and married calm of states

Quite from their fixure! O, when degree is shaked,

Which is the ladder to all high designs,

Then enterprise is sick! - Troilus and Cressida, Act I, Scene iii.

https://folgerpedia.folger.edu/Idolatry:_Icons_and_Iconoclasm

Shakespeare and the Civil War are forever linked. All the major players had a connection to the Bard, and some might surprise you:

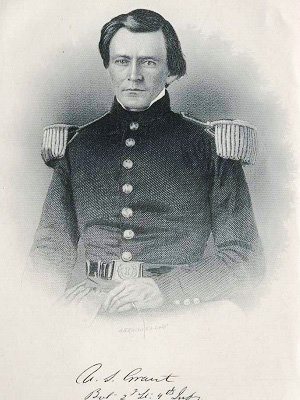

1. Did you know US Grant played a woman in a Shakespeare play!

We rarely see images of the future general and future president without his well-kept beard, but if this apocryphal tale is true, Grant might have grown a beard after he was embarrassed by the reaction of his fellow soldiers during a performance of Othello, where Grant rehearsed the part of Desdemona:

That December, officers decided to stage “Othello.” They looked for someone to play the beautiful Desdemona. Grant was urged to try out for the part. He had a trim figure and almost girlish good looks; his friends called him “Beauty.” Though the costume fit perfectly, the officer playing the Moor couldn’t look at Grant without laughing. They sent to New Orleans for a professional actress to play Desdemona. After that, Grant grew a beard to hide his girlish good looks. He was “Beauty” no more.

Civilwartalk.com

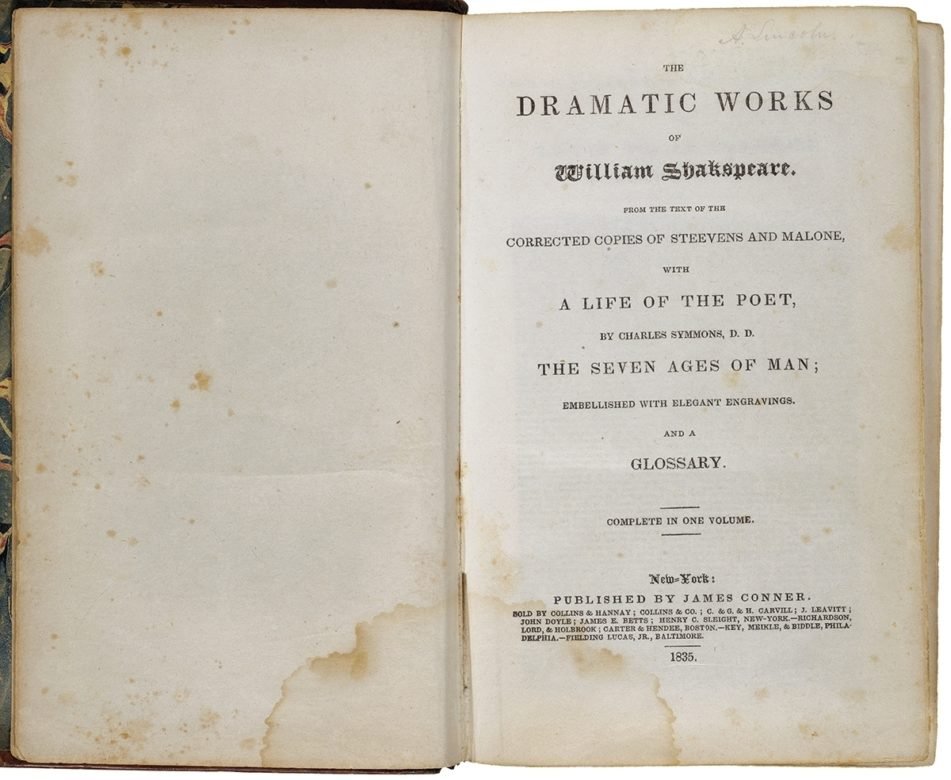

I’ve talked before about how, to the South, President Lincoln was as big a tyrant as Julius Caesar, and how John Wilkes Booth was determined to cast himself as a real life Brutus

https://www.whitehousehistory.org/the-american-presidents-and-shakespeare

What you might not know is that Lincoln’s favorite Shakespeare play was Macbeth. I find a more fitting character for the compassionate and eloquent president would be the good King Duncan from Macbeth. According to Whitehousehistory.org. Lincoln quoted some lines about the good king’s death, a few days before his own:

On Sunday, April 9, 1865, with the war over, he was returning to Washington on the River Queen from City Point, Virginia, where he had visited the front, and he talked Shakespeare to his companions, read aloud to them, and recited his favorite passages from memory. He spent most of his time on Macbeth. “The lines after the murder of King Duncan. Lincoln’s companions were struck by the slow, quiet way he read the lines:

Whitehousehistory.org.

“Duncan is in his grave;

After life’s fitful fever, he sleeps well,

Treason has done his worst; not steel, nor poison,

Malice domestic, foreign levy, nothing can touch

him farther.”

When Lincoln finished, he paused for a moment, and then read the lines slowly over again. “I then wondered,” reflected one of his friends, “whether he felt a presentiment of his impending fate.”

If you choose to sign up for my Outschool class: The Violent Rhetoric Of Julius Caesar, I compare Antony’s speech, (which essentially started a civil war in Rome), with Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. I also discuss John Wilkes Booth and his obsession with the character Brutus.

I was pretty shocked to learn this one, and it took a while before I found a decent amount of evidence to justify reporting on it here, but apparently a few ex confederates fled to England after the war, and took refuge at inns and houses in and around Stratford, including Royal Leamington Spa, which is a town just 12 miles from Stratford-upon-Avon.

I had scarcely become domesticated before the visits of the Confederates began, & we have now quite a little Southern Society. Mr & Mrs Fry of N. York, & Mrs Leigh reside very near us. Mr & Mrs Westfeldt also; but just now they are absent. Mr & Mrs Dugan, Mr & Mrs & the Misses

Nathaniel Beverley Tucker, US Consul, 1861

Stewart, Mrs Hanna & Miss Reynolds, Mr & Mrs Clements, Mr & Mrs Skinner, Capt Flinn, & various others who are here, off & on, compose the little nest of Confederates in Leamington.

England was anti Slavery in the 1860s but they were also partners with the Confederates in the lucrative cotton trade. CSA president Jefferson Davis dispatched a number of ambassadors and negotiators to hopefully gain support from the English to help them fight the US in the Civil War.

Once President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, England politely declined to aid the confederacy militarily, but Davis’ visits opened the door for Confederates in England, and that is why they wound up living in Leamington Spa.

While they were there, some purchased English warships to become part of the Confederate Navy. Some even got married!

1. Shakespeare and US Presidents: Whitehouse History.com

2. Civilwartalk.com

3. New York Times: John Wilkes Booth

4. Leamington History: “A Confederate Nest in Leamington.”

However, the Romans gave way before the good fortune of the man and accepted the bit, and regarding the monarchy as a respite from the evils of the civil wars, they appointed him dictator for life. This was confessedly a tyranny, since the monarchy, besides the element of irresponsibility, now took on that of permanence

Under these circumstances the multitude turned their thoughts towards Marcus Brutus, who was thought to be a descendant of the elder Brutus on his father’s side, on his mother’s side belonged to the Servilii, another illustrious house, and was a son-in‑law and nephew of Cato. 2 The desires which Brutus felt to attempt of his own accord the abolition of the monarchy were blunted by the favours and honours that he had received from Caesar. 3 For not only had his life been spared at Pharsalus after Pompey’s flight, and the lives of many of his friends at his entreaty, but also he had great credit with Caesar. 4 He had received the most honourable of the praetorships for the current year, and was to be consul three years later, having been preferred to Cassius, who was a rival candidate. 5 For Caesar, as we are told, said that Cassius urged the juster claims to the office, but that for his own part he could not pass Brutus by.105 6 Once, too, when certain persons were actually accusing Brutus to him, the conspiracy being already on foot, Caesar would not heed them, but laying his hand upon his body said to the accusers: “Brutus will wait for this shrivelled skin,”106 implying that Brutus was worthy to rule because of his virtue, but that for the sake of ruling he would not become a thankless villain. 7 Those, however, who p589 were eager for the change, and fixed their eyes on Brutus alone, or on him first, did not venture to talk with him directly, but by night they covered his praetorial tribune and chair with writings, most of which were of this sort: “Thou art asleep, Brutus,” or, “Thou art not Brutus.”107 8 When Cassius perceived that the ambition of Brutus was somewhat stirred by these things, he was more urgent with him than before, and pricked him on, having himself also some private grounds for hating Caesar;

So far, perhaps, these things may have happened of their own accord; the place, however, which was the scene of that struggle and murder, and in which the senate was then assembled, since it contained a statue of Pompey and had been dedicated by Pompey as an additional ornament to his p597 theatre, made it wholly clear that it was the work of some heavenly power which was calling and guiding the action thither.

Well, then, Antony, who was a friend of Caesar’s and a robust man, was detained outside by Brutus Albinus,110 who purposely engaged him in a lengthy conversation; 5 but Caesar went in, and the senate rose in his honour. Some of the partisans of Brutus took their places round the back of Caesar’s chair, while others went to meet him, as though they would support the petition which Tulliusº Cimber presented to Caesar in behalf of his exiled brother, and they joined their entreaties to his and accompanied Caesar up to his chair. 6 But when, after taking his seat, Caesar continued to repulse their petitions, and, as they pressed upon him with greater importunity, began to show anger towards one and another of them, Tullius seized his toga with both hands and pulled it down from his neck. This was the signal for the assault. 7 It was Casca who gave him the first blow with his dagger, in the neck, not a mortal wound, nor even a deep one, for which he was too much confused, as was natural at the beginning of a deed of great daring; so that Caesar turned about, grasped the knife, and held it fast. p599 8 At almost the same instant both cried out, the smitten man in Latin: “Accursed Casca, what does thou?” and the smiter, in Greek, to his brother: “Brother, help!”

9 So the affair began, and those who were not privy to the plot were filled with consternation and horror at what was going on; they dared not fly, nor go to Caesar’s help, nay, nor even utter a word. 10 But those who had prepared themselves for the murder bared each of them his dagger, and Caesar, hemmed in on all sides, whichever way he turned confronting blows of weapons aimed at his face and eyes, driven hither and thither like a wild beast, was entangled in the hands of all; 11 for all had to take part in the sacrifice and taste of the slaughter. Therefore Brutus also gave him one blow in the groin. 12 And it is said by some writers that although Caesar defended himself against the rest and darted this way and that and cried aloud, when he saw that Brutus had drawn his dagger, he pulled his toga down over his head and sank, either by chance or because pushed there by his murderers, against the pedestal on which the statue of Pompey stood. 13

And the pedestal was drenched with his blood, so that one might have thought that Pompey himself was presiding over this vengeance upon his enemy, who now lay prostrate at his feet, quivering from a multitude of wounds. 14 For it is said that he received twenty-three; and many of the conspirators were wounded by one another, as they struggled to plant all those blows in one body.

-Plutarch’s Life Of Caesar

James Shapiro in his book 1599, addresses the common complaint that in the play that bears his name, Julius Caesar dies halfway through the play and has little time onstage to make a connection with the audience. The play is about tyrananicide, what causes it, what it looks like, and especially its aftermath. In a time when Jesuits and Catholic radicals threatened to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, Shakespeare wrote a powerful story about how fragile government systems can be; how striking the head off Rome leads to anarchy and sometimes tyranny.

Julius Caesar’s success as a politician was deeply tied to his success as a military leader. Therefore studying the Roman army during Caesar’s life helps one understand why he was so popular and why the Senate wanted him dead.

Caesar was commander (or legatus legionis) of the 10th mounted legion, which means his soldiers were mounted on horseback. Caesar was in charge of maintaining control over the warring tribes in Gaul (modern day France). Each legion was organized into 6 companies (cohorts) of 100 men, led by a Centurian, Source : http://thedioscuricollection.com/ejercito_romano_en.php

According to Imperiumromium.com, Caesar helped reform his army, and his Centurians carried out many different campaigns in Gaul:

As you can see, his soldiers were mainly armed with helmets, leather armor, and their large shields and Gladius swords. Below is an exploration of the different parts of the Roman uniform:

https://costumes.lovetoknow.com/roman-soldier-uniform

One way to learn about Julius Caesar is to learn about the weapons he used as general of on of the most fearsome legions in Rome. In this blade-forging competition from the History Channel, 2 master blacksmiths forge their own versions of a Roman Gladius, and put them to the test!

In honor of Black history month, and the impending Ides of March, I’d like to highlight two wonderful black British actors, Ray Fearon and Paterson Joseph, two of the best actors at the Royal Shakespeare Company. In this video, they discuss their interpretation of Act III, Scene ii of Julius Caesar, in a groundbreaking production set in Africa.