Last month, I took a short vacation to Las Vegas, where, as some of you know, I went to Area 15 and the Omega Mart Exhibit. I also visited the Las Vegas Mob Museum. I’ve been fascinated by the mob for years. The Mob (AKA The Outfit), has within its many threads a potent combination of corruption, seduction vice, and violence all hidden behind the veneer of honorable men who do what they feel they have to to protect their families and their communities.

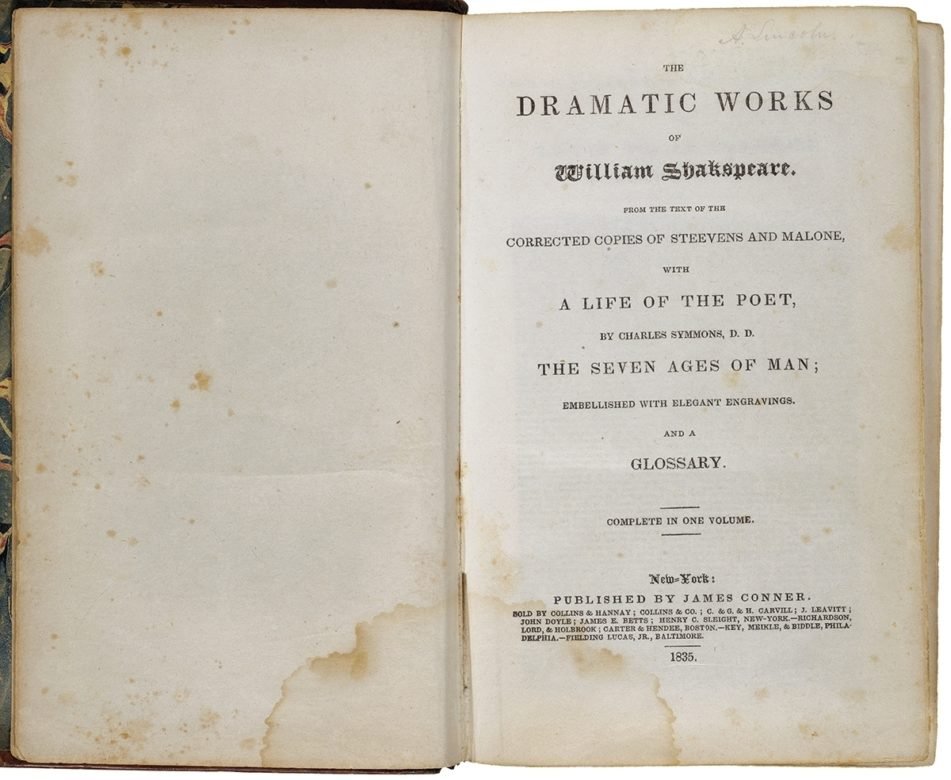

Not surprisingly, while at the museum, I saw parallels between the history of organized crime and Shakespeare, specifically his most popular history play about a powerful family that takes over the crown of England in a brutal turf war, and then one of its most feared soldiers bribes, intimidates, and murders his way to the top; Richard III.

A Protection Racket: Feudalism vs. La Cosa Nostra

The structure of the mafia paralleled the feudal system. In a world where a police force didn’t offer much protection for marginalized communities, the mafia thrived by offering protection for these communities, (especially to immigrants and people of color in the 19th and early 20th century).

Much earlier than that, the feudal system of the middle ages, which started to crumble after Richard’s reign ended, was designed specifically so poor peasants could get protection from wealthy landowners after the fall of the Roman Empire. These lords offered the protection of their knights to these peasants i. Return for labor and a percentage of their income working the field. Like the mafia, these peasants paid tributes to their lords and these lords demanded loyalty. In the museum, there’s an interactive video where you can become a ‘made man,’ which means become an official member of a mafia crew. Like a king knighting a lord, this ceremony meant pledging your life to your superiors, and being at their beck and call no matter what. In addition, like medieval knights, mafiosos were not allowed to murder other made men without permission from their capo or boss.

However benevolent they might appear, In both cases the Dons and the medieval lords were extorting their underclass. Failing to pay tribute to their lords would cause the peasants to lose their lands, and any disloyalty to the mafia would be severely punished. These powerful, violent thugs used their private armies to intimidate the weak into giving them what they wanted.

Part II: The Two Families

To thoroughly explain the parallels between the Wars of the Roses and the mob, I need to make clear that Richard iii is more than just the story of one man’s rise to power, although there are also mafia stories that fit this mold such as Scarface, White Heat, and the real-life story of Al Capone.

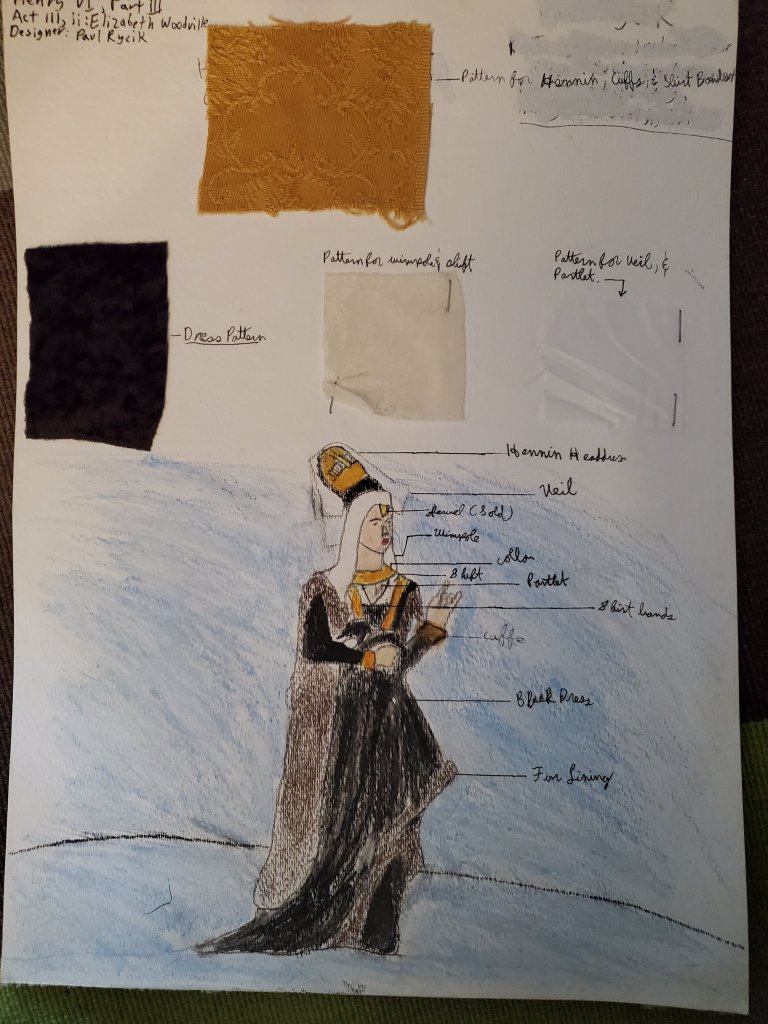

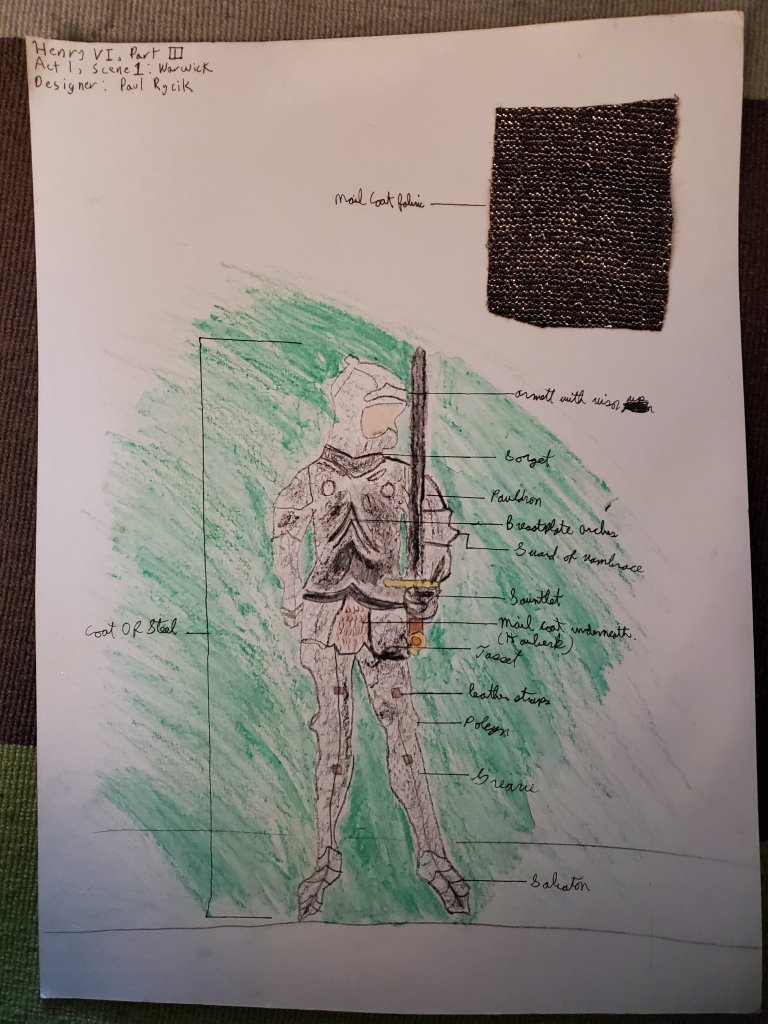

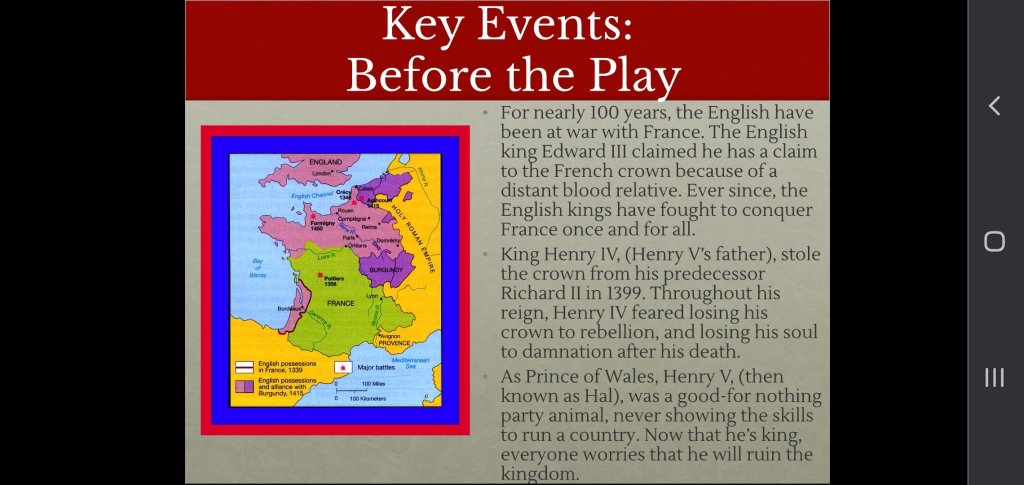

As this hilarious “weather report” from “Horrible Histories,” makes clear, during the Wars of the Roses two powerful families, (each with a claim to the English crown) fought each other in a brutal turf war. As Shakespeare characterizes in his play Henry VI, Part III, the battles between the houses of York and Lancaster shook England like a mighty storm, and for a while it was hard to tell who would prevail:

Henry VI. This battle fares like to the morning's war,Henry VI, Act II, Scene i

When dying clouds contend with growing light,

What time the shepherd, blowing of his nails,1105

Can neither call it perfect day nor night.

Now sways it this way, like a mighty sea

Forced by the tide to combat with the wind;

Now sways it that way, like the selfsame sea

Forced to retire by fury of the wind:1110

Sometime the flood prevails, and then the wind;

Now one the better, then another best;

Both tugging to be victors, breast to breast,

Yet neither conqueror nor conquered:

So is the equal of this fell war.

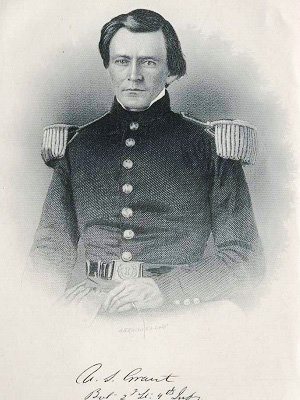

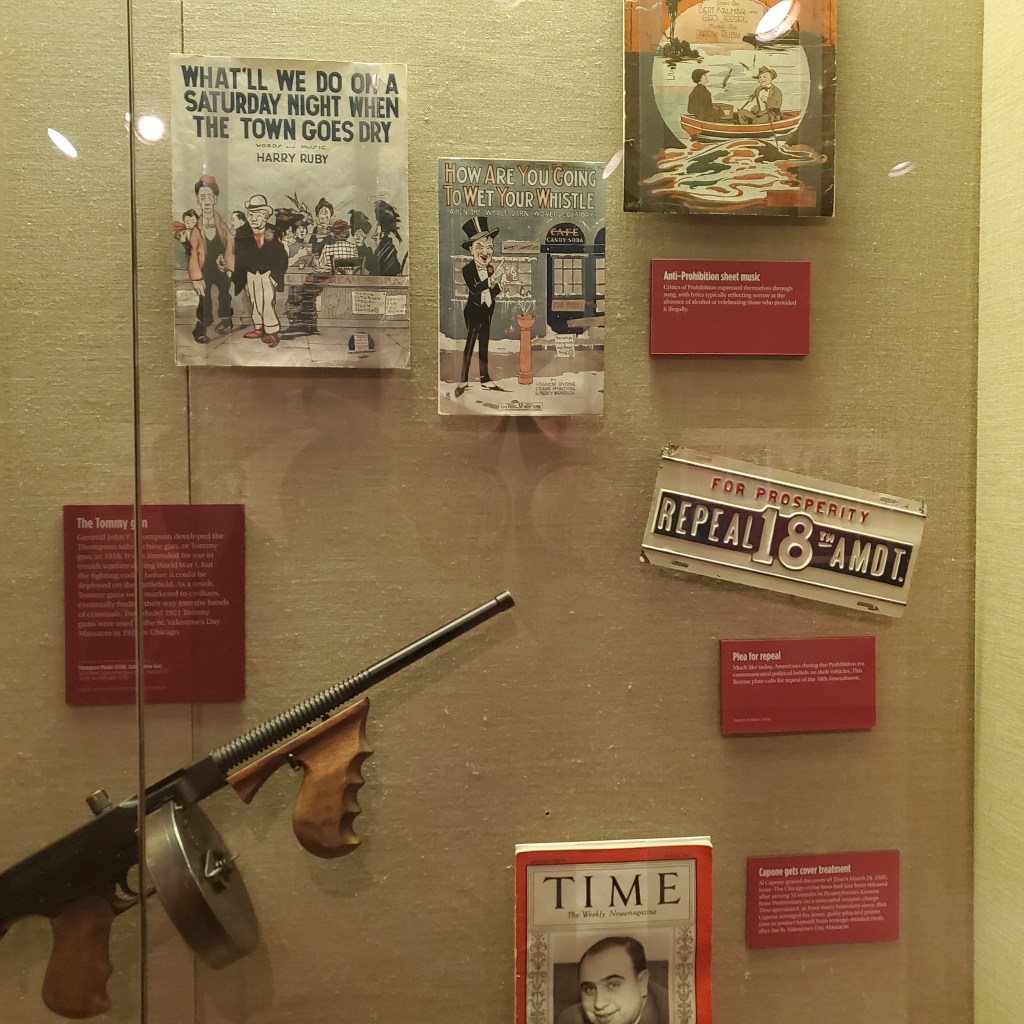

During the Wars of the Roses, it was King Henry’s incompetence and mental illness that gave the Yorkists the ability to challenge the House of Lancaster for the crown. In the 1920s, the passage of the 18th amendment, (which made alcohol illegal, and thus a profitable commodity for organized crime), that allowed the mob to rise to unheard-of power through illegally buying, distributing, and selling alcohol. As the photo and subsequent video shows, Prohibition largely led to the rise in organized crime in America, especially in Chicago. During Prohibition, the Italian Sough-side Gang fought for control of Chicago’s bootlegging trade and subsequently destroyed their competition from the Irish gangs through corruption, intimidation, and violence.

The Don rises- Richard Vs. Al Capone

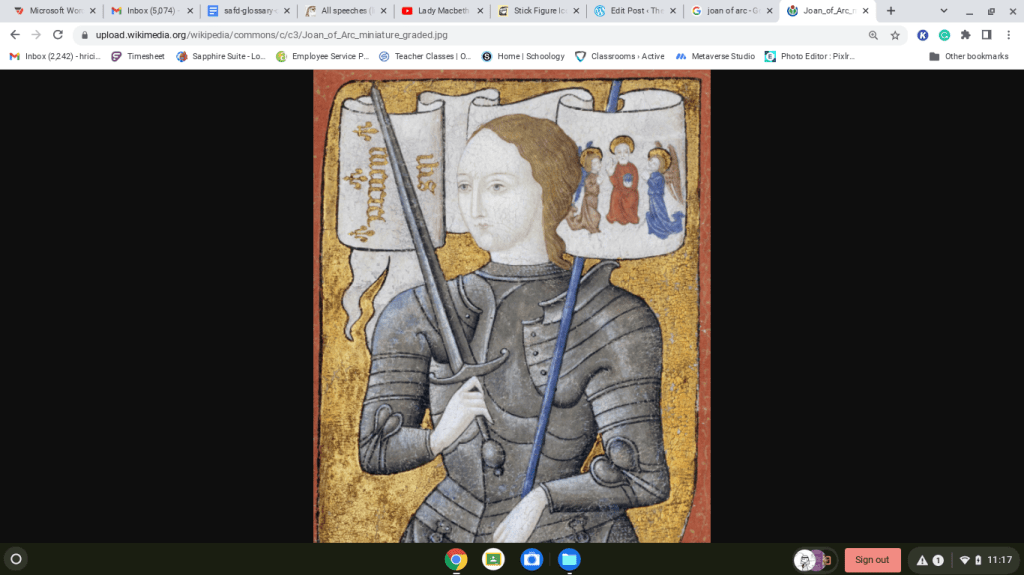

Like the Italian and Irish gangs In Prohibition-era Chicago, the Yorkist and Lancastrian armies battled for the English throne. As Ian McKellen’s excellent movie (set in the 1930s) shows, Richard was instrumental in destroying the leading Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury, including Prince Edward and King Henry.

In Chicago, the most feared mobster soldier was Al Capone, who many scholars believe was responsible for killing off high ranking members of the Irish gang during the infamous St. Valentines Day Massacre, where the gang members were ‘arrested’ by South Side gangsters disguised as cops. As the Irish stood against the wall with their hands behind their heads, the phony cops pulled out Tommy guns from their coats and let out a hail of bullets on their unsuspecting quarry.

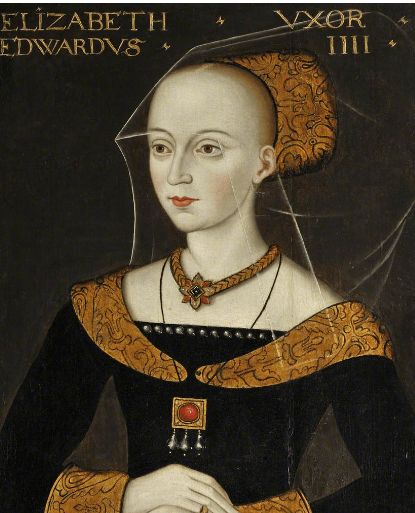

In Shakespeare’s play, the only Lancastrian to survive the war is Queen Margaret, wife to the murdered King Henry, and mother to the slaughtered Prince Edward. In this scene from Al Pacino’s “Looking For Richard,” she curses Richard for his cruel slaughters. It’s not surprising that Pacino was so drawn to Richard II that he starred in and directed this film. After all, Pacino is famous for playing mafia characters who slaughter their way to the top.

Once Capone killed the competition, he ruled a multimillion-dollar empire of bootleggers and maintained that empire through corruption, intimidation, and by constantly playing innocent, just like Richard himself.

Hypocrisy, Corruption and hidden violence

“Men in general judge more by the sense of sight than by the sense of touch, because everyone can see, but few can test by feeling. Everyone sees what you seem to be, few know what you really are; and those few do not dare take a stand against the general opinion.”

Niccolo Machiavelli

Both Richard III and mobsters are masters of double-speak, that is, seeming to say one thing and meaning something else. Look at this passage where Richard talks about killing his nephew, then denies it:

- Richard III (Duke of Gloucester). [Aside] So wise so young, they say, do never

live long. - Prince Edward. What say you, uncle?1650

- Richard III (Duke of Gloucester). I say, without characters, fame lives long.

[Aside]

Thus, like the formal vice, Iniquity,

I moralize two meanings in one word.

Las Vegas: The town that bedded and abetted the mob.

After Al Capone’s demise and the repeal of Prohibition, the mafia found another vice to capitalize on: gambling. As the video below indicates, using their connections with the Teamsters Union and midwestern bookmakers, the mob in the midwest financed, built, and run almost every casino in Las Vegas, including The StarDust and the Hassienda. Once the casinos were built, the mob extorted millions of dollars from the casinos every month!

The profits from the casinos bought the mob even more power and influence, but this skim depended on making sure the bosses controlled their underlings, and defended their casinos from cheaters and snitches, which is why they defended their casinos through intimidation and violence.

Murders in The White tower and the city of sin.

When Richard of Gloucester starts his quest to become king, he begins by convincing his brother King Edward to execute his other brother George. Richard bribes the murderers to kill George before the king can reverse the death sentence. Richard has thus eliminated another obstacle in his way, and gained two loyal followers who will do anything for his gold.

The mafia dealt the same way with traitors, stool pigeons, and anyone who tried to challenge the bosses. Look at this tour of the Mafia museum, where the grandson of the gangster Meyer Lansky starts by reminiscing about the glamourous lifestyle of Las Vegas mobsters, but the tour quickly takes a dark turn as Lansky II talks about how his grandfather ordered brutal executions for anyone who crossed The Las Vegas Outfit.

It was an enormously interesting trip going to the Mafia Museum, and if you can get out to Las Vegas, be sure to visit, (don’t forget the password to visit the speakeasy bar in the basement!) It was eye-opening for me how prevalent the sort of corrupt protection racket that started in the middle ages and continued into most of the 20th century helped define The Wars of the Roses and the mafia. As long as the strong prey on the weak and the law can’t protect everyone equally, these kinds of violent thugs will be lurking in the shadows, waiting for a shot at the crown.