Thanks to WordPress’ new interface, it’s easier for me to read what other bloggers have to say about the topics I write about. One trend I’ve noticed is the question that’s been boiling underneath the surface of a lot of people in our culture: “Should Shakespeare be ‘cancelled’?” It’s an interesting question and definitely merits discussion.

It is also a question that has some basis reality: Shakespeare was taken off the list of required reading of of schools in New Zealand. In 2007, The American Council Of Trustees and Allumni published a report called “The Vanishing Shakespeare,” about the number of colleges who no longer require English majors to take Shakespeare courses. If you read my post on Romeo and Juliet, you will recall that one of the main reasons why we have Shakespeare as a requirement in American high schools is that he is required reading in many colleges. So this could be part of a trend that extends to primary as well as secondary schools as well.

Many academics, (myself included), are wondering about Shakespeare’s status in education, and whether or not he will continue to be a staple of all English language curricula. So what I want to do with this essay is to ask the question, “Should Shakespeare be cancelled,” as well as”Should he not be cancelled? and “What even is cancelling and how does apply to somebody who is already long long dead now?”

First off, cards on the table: I am a white man, (with a beard), who has been studying Shakespeare for 20 years. I have a very clear bias; I would never advocate for Shakespeare being taken out of any schools. That said, I see merits to parts of the argument, and I do not believe that these teachers who are reexamining Shakespeare’s place in education are inherently wrong. Nor do I believe if that there is no merit to changing the way educators teach Shakespeare in our schools, (more on that later). My point is to write a thoughtful reflection about the nature of Shakespeare as a writer, his status within our culture, his status within the educational establishment, and how changing that is not necessarily a bad thing.

Part One: the arguments for cancelling Shakespeare

When I read the article “Why I am rethinking Teaching Shakespeare In My English Classroom,” by teacher Christina Torres, I noticed a lot of her arguments centered around diversity quotas and simply not having the class time to devote to Shakespeare. This is entirely understandable. Shakespeare has been dead for 400 years, which means language has changed a lot since his heyday.

Shakespeare poses several unique challenges in education. He wrote in an obscure form of poetry that is no longer fashionable. You have to read footnotes. Although 95% of the words he used are still used today, they are used in a very unique syntax. Furthermore, I come to teaching Shakespeare from the perspective of somebody who studied theater, acting, Elizabethan history, and everything that that is required to teach Shakespeare, but many teachers do not. My point is I can understand why a teacher feels that he or she does not have the time, energy, or the learning required to give Shakespeare the space that he so clearly demands.

The question of Shakespeare’s status in our classrooms also raises subtle questions about diversity. Many curricula these days emphasize diverse writers and try to highlight the cultural contributions of women, people of color, and LGBTQ people, and as far as we know, Shakespeare fit into none of these groups.

This educational initiative is a part of the anti racist initiative and I as an educator I am fully on board with this. I love to be in a classroom where Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Lorraine Hansberry, Mary Shelley, and Truman Capote share the same shelf is William Shakespeare, but ever since the 18th century Shakespeare and cultural nationalism have been inexorably linked.

Almost since the beginning of Shakespearean scholarship, American and British critics have sought to venerate Shakespeare as the peak of British culture, and thus the peak of human culture as well. It’s not a coincidence that we celebrate National Poetry Month the same month as Shakespeare’s birth and death. Also, even though we don’t know for sure when Shakespeare was born, we celebrate it on April 23rd, St. George’s Day, thus forever linking England’s greatest poet, with its patron saint. George Bernard Shaw, (an Irishman), coined the term ‘bardolotry,’ to describe the treatment of Shakespeare by the English as if he were a god and the evidence is quite damning:

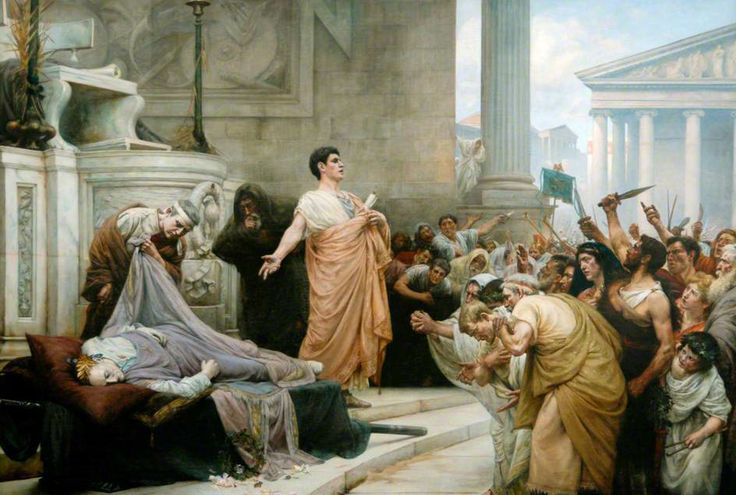

Just look at this painting where Shakespeare is portrayed as in the same pose and with the same reverence as the baby Jesus. This reverence carried over to poetry, music, festivals, and of course, to the classroom. As I wrote in My Romeo and Juliet post, since the beginning of American public education, Shakespeare was an indispensable fixture in American schools, and thus, prompting American writers like Mark Twain to grumpily refer to Shakespeare and other classics as “Something everyone wants to have read, but nobody wants to read.”

Countless textbooks refer to Shakespeare as the greatest writer in the English language, and possibly the greatest writer ever. Ralph Waldo Emerson once preached that Shakespeare was: “Inconceivably wise.” The god-like aura around Shakespeare has made him nearly impervious to criticism and English speakers on both sides of the Atlantic have claimed Shakespeare as their gospel. Being an English speaker means having the God-Shakespeare on your side, and if you have God on your side historically speaking, you can justify anything.

The British were keen to elevate Shakespeare to this godlike status partially because it showed that their culture was superior to others. Let’s not forget that Shakespeare’s last play The Tempest is about a man with book learning who goes off and colonizes an island whose inhabitants seem savage and uneducated. If our goal as educators with adding anti racist education is to show that all voices are valid, to highlight the contributions of every ethnic group, and to refute the notion that white culture is in any way superior to any other, then to a certain degree, we must knock Shakespeare off his literary pedestal.

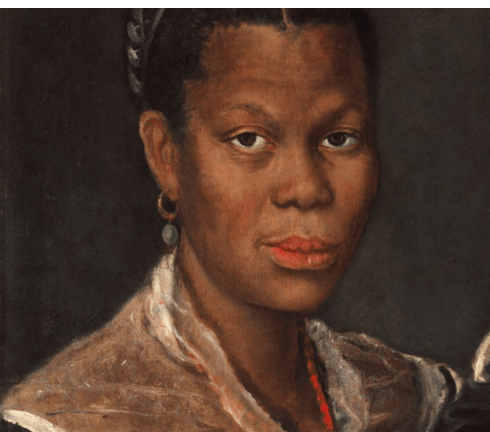

We also should not a take a blind eye to the anti-POC and mysoginist language in some of Shakespeare’s plays. For instance one line I deeply despise in Romeo and Juliet is the line where Romeo refers to Juliet by saying she “Hangs upon the cheek of night like a rich jewel in Ethiop’s ear” (A black woman wearing an earring).

This statement contrast beauty, specifically the beauty of white skin, with the “ugliness” of a black woman’s ear. Shakespeare uses this metaphor several times in several plays, establishing white as beauty and black as the aberration.

I bring this up not to say that Shakespeare should be cancelled and hated because of this racially insensitive language, because he’s not the only one who does it. All you have to do is Google “Who’s the fairest one of all?” to realize that for centuries, fair skin, beautiful skin, and white skin meant the same thing. As Dr. Grady says in the video above, having an honest discussion of Shakespeare’s language and his culture’s attitude towards race is an opportunity to teach critical race theory in the classroom, and to teach students to recognize and deplore dehumanizing language, which though poetic to white Elizabethans, is hurtful and dehumanizing to people of color. In short, banning or condemning Shakespeare is counter productive, but examining his language, culture, and politics with a critical eye is a very useful and important exercise.

Part 2 why Shakespeare doesn’t deserve to be cancelled

I’ve established that Shakespeare has connections with some very dark moments in a European history and he should not be celebrated merely because of he was white or because he was British. I believe that Shakespeare’s contributions to the English language as well as drama and the arts still makes him worthy of study by students. As this video from the New York Times shows, students need at least a basic understanding of Shakespeare to understand western culture:

I believe that, as long as we educators don’t indulge our bardolotrous tendancies, and keep Shakespeare in the context of the period in which he lived, we can still teach him in a way that will benefit our students.

One small way to put Shakespeare in context is very simple: STOP USING THE TERM “RENAISSANCE.” Most scholars now refer to Shakespeare’s time period as the Early Modern Period, not The Renaissance, which was an honorific term that people used during Shakespeare’s time period. The term RENAISSANCE, meaning the rebirth of classical learning and by extention the rebirth of sophisticated European culture, can give the impression that it was only a period of study and artistic achievement, leaving out colonization and racial and political tension. I find Early Modern Period a very useful descriptor because like it or not, Shakespeare’s culture influenced ours, therefore an understanding of him is very much understanding of where we came from. Learning from Shakespeare is like learning from history- we cannot shy away from the mistakes of the past, nor should we flat out reject its benefits.

it should be noted that a lot of the good scholarship in the last to the last 50 or 60 years has been tasked with putting Shakespeare back into his historical context and trying to reclaim his staus as a man of his time. Dr. Stephen Greenblatt of Harvard University helped coin the term ‘new historicism’ which emphasizes learning about the culture of a writer’s time period. To New Historicists (such as myself), Shakespeare is no longer considered a great man of history, but a man shaped by the culture of his time, which is to say a man who had good parts and bad parts much like history itself. This is the approach that I think should be taught in American schools highlighting how Elizabethan culture shaped Shakespeare, and how he shaped our culture in turn.

Comparing Shakespeare to history, especially American history, is very useful in American schools. Like the founding fathers Shakespeare reached towards an ideal. He wrote plays about ideal kingship, even though kingship is a cruel and autocratic system of government. He wrote romances about young lovers who follow the wonderful idea of love at first sight, even though in reality that concept is somewhat rare, and very often fraught with peril. And like Shakespeare, people often ignore the flaws and human failings of the founding fathers too. Look at this mural painting of The Apotheosis of Washington, which still looks down on mortals from the US capital building in Washington DC.

Much like the founding fathers’ document that declares that all men are created equal, we can appreciate Shakespeare’s plays but also be aware of their flaws. Both documents were written by a flawed human being with a very narrow understanding of the wider culture and world in which he lived, but one who did his best to try and write works that would benefit all of mankind. As educators we can teach students to be inspired by this work, and seek to have a greater understanding of “The Great Globe Itself,” with the benefit of hindsight, so they may become enlightened citizens of the world, true Renaissance Men, Women, themselves.

So if I truly believe, (and I do), that Shakespeare is still relevant and has something to say to people regardless of their culture or cultural and racial backgrounds regardless of what time period they were born in and regardless of gender, how then can we teach him in classrooms in responsible and nuanced way?

What to do?

[ ]Give a cultural context to the play you study. A culture that is the direct ancestor of our own, but one that was frought with Colonialism, Casual racism, (especially in language), Sexism, Patriarchy, and Homosexual oppression. Not to toot my own horn, but this is what I tried to do with my Romeo and Juliet Website: https://sites.google.com/d/1iLSGjbllxU-ZwyrUya_xHtjojSCg9pd6/p/12GhgKdJr63wmTcm6TTvkZ-ROmUnALKQi/edit

-Give students the chance to rewrite or reword the more problematic elements, such as Romeo’s creepy stalking of Juliet,

-Highlight Shakespeare calling attention to patriarchial issues: Capulet in Act III, v, Friar Lawrence comparing love to gunpowder. Juliet raging against arranged marriage, etc.

- Celebrate Shakespeare’s positive contributions to race relations: Othello was the first black hero on the London stage and the role helped generations of black actors get their start in theatre. There’s your modern bardolotry, Shakespeare not as “Inconceivably wise,” Inconceivably woke! You can also look at the proud tradition of color blind casting in Shakespeare’s performance history, such as Orson Wells’ “Voodoo Macbeth.”

- Do some research on modern productions that translate the themes into a modern concept.

To sum up- cancelling Shakespeare doesn’t mean vilifying him. It means re-examining his role in our culture, and teaching students to appreciate the benefits, and try to correct the damages that his culture has brought to our own. We can’t change the past, but we can learn from it. As for Shakespeare himself, no amount of legitimate criticism will keep people like me from enjoying his plays. If anything, I appreciate even more the breadth and depth of his writing the more I learn about the culture in which he lived. I like to think that, if Shakespeare knew people would be talking about him in school, he’d echo the way Othello said he wanted to be remembered, to “Speak of me as I am, Nothing extenuate.” And that we heed the words of Ben Johnson in the dedication to the First Folio, when we think of treating Shakespeare as an icon.