If you read my blog for an extended period of time, or if you listen to my podcasts, or if you’ve taken any of my classes online, then I probably told you the notion that I believe that you could find Shakespearean roots in just about every single work of Western and quite a few of Eastern literature. Shakespeare is ingrained in our culture and therefore a lot of his influence can be felt in almost every bit of media we take in. One of my favorite ways to illustrate this, is by looking at Disney movies, trying to prove that every Disney story is at least a little bit inspired by a Shakespeare play as you’ve seen from my comedy series if Shakespeare wrote for Disney:

I had an enormous challenge on my hands when Disney came out with the new film Encanto. Previously I’ve found it very easy to deconstruct Disney film plots and spot their Shakespearean roots: Pocahontas is Romeo and Juliet by Disney’s own admission, Aladdin is basically the Tempest, Mulan is Twelfth Night, and the Lion King is Hamlet, (as many people have pointed out).

Encanto was really really hard because it is such a fresh and original story. It is deeply rooted in Columbian culture, so trying to defend the notion that it has anything in common with the works of a 400-year-old English male playwright is a tough claim. I don’t mean to suggest that this movie is a deliberate reinterpretation of Shakespeare. That would be insulting and limiting to the breadth of the story. My main purpose with this post is to show how universal and powerful these two stories are- to pay Encanto the compliment that, like Shakespeare, the story transcends cultural and historical boundaries and tells a story we can all relate to, and this is why I am making this bold claim, that Encanto resembles King Lear, albeit with a happy ending.

Mirabelle- the Cordelia of “Encanto”

It was hard for me to realize that Encanto resembles Lear because the Lear character is not the focus of the movie; the focus of the movie is the Cordelia character, Mirabelle. If you’ve read King Lear , then you know that Cordelia is vital to the first 2 scenes of the play, and then goes offstage until Act 4 when where she is reunited with her father in prison, then cures his madness just long enough for her to be hanged. Her death is the darkest, grimmest, bleakest moment that Shakespeare ever wrote. She is the heart of the play and Lear’s failure to listen to her forms the heart of the play’s message; when an older generation clings to power and power or money or status or anything else besides their family, ultimately they suffer tremendously.

In his first line, King Lear says that he wants to give up his kingdom, conferring it to his daughters and their husbands, but what he is really trying to do is to get his daughters to say they love him and to give them the kingdom as a reward.

This deal also has more strings attached; Lear basically says: “Now that I’ve given you my kingdom, you have to house me in your castle with a retinue of 100 knights.” And the only child who really loves Lear and has his best interest in heart is Cordelia, and Lear violently renounces his parental claims on her and banishes her from the kingdom along with her husband the king of France.

The Lear of “Encanto”

So who is the King Lear figure in Encanto? Abuela Alma! Think about it, she is an older person who is spending the whole play clinging and holding on to the power that the Magic Candle gives to her. She spends the whole movie trying to protect the Encanto, and when she mistakenly believes that Mirabelle is a threat, she pushes her away. She rules her other children Papa, Julietta, and Brunowith an iron fist, and she flies into panics and rages whenever anything seems to threaten the safety of the candle. For example, when Bruno gets the magic prophecy that Mirabelle might destroy the house and destroy the Encanto, Abuela refuses to let Mirabelle talk to anybody ever and generally acts in a cruel controlling way.

Look at this passage when Lear rejects his loving daughter Cordelia. Given what I’ve mentioned- the fists of rage, the clinging to supernatural powers, and the controlling demands for loyalty and obedience from his children, whom does King Lear sound like?

Lear:

For, by the sacred radiance of the sun,

The mysteries of Hecate and the night;

By all the operation of the orbs115

From whom we do exist and cease to be;

Here I disclaim all my paternal care,

Propinquity and property of blood,

And as a stranger to my heart and me

Hold thee from this for ever. The barbarous Scythian,120

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

Be as well neighbour'd, pitied, and reliev'd,

As thou my sometime daughter. King Lear, Act I, Scene i.

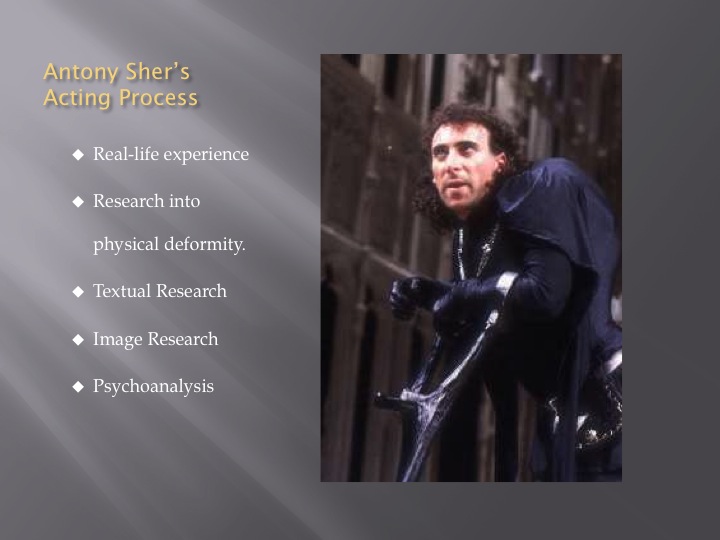

As Ian McKellen explains in this interview, like Abuella, Lear clings to power, which he derives from supernatural forces, ignores people who care about him, and believes that his authority is absolute:

Trauma and Violence in Encanto and King Lear

Marxist critics believe that Lear’s power is based on violence, (like most medieval kings), and violence is actually connected to Abuela as well. Let’s not forget that the candle was forged after the faceless men with machetes attempted to murder Abuela and her whole village. The candle is Abuela’s power, but it is also a constant reminder of the violence that she escaped. It is also therefore a symbol of her trauma. Perhaps these characters became so controlling, distant, and cold because of the trauma they endured. Lear is supposed to be a king of Britain back in the pre-Christian era of the Anglo-Saxons so he must have seen countless invasions:

The former king says himself that he’s fought in wars with his “Good biting falchion” (a kind of sword). Whether they’ve seen falchions or machetes, these characters have seen violence and want to protect themselves against seeing the pain of it again, and ultimately it is their children that suffer because of it.

In King Lear, the kingdom is ripped apart between the three daughters, and in Encanto, the house is literally ripped apart by the rift between the family and Abuela. Lear foolishly tries to bribe his daughters into flattering him; promising them the kingdom if they demonstrate how much they love him. Therefore Lear demands obedience and love and expects his family to fawn on him as if they were his subjects, not his family.

Lear’s favorite daughter Cordelia refuses to take the bribe, so she says nothing. Lear is enraged and treats this small disobedience like an act of treason:

Arguably Abuella makes the same mistake. She treats her children like her subjects too and exploits their gifts in order to keep the community happy. Her fear of losing her home is the reason she pushes the Madrigals to be indispensable to the community. Think of the psychological and physical pressure Louisa mentions in her song:

As you can see in this video, Lin Manuel Miranda, who wrote the music for Encanto, was actually inspired by Shakespearean verse for the lyrics and rhythms in her song “Surface Pressure.” Whether or not he or the screenwriters were inspired by “Lear,” the fact remains that Mirabelle suffers much like Cordellia. She also can’t stand to see her sister Louisa in pain like this, so she sets out to save her family, which forces her to confront Alma. Much like Lear and Cordelia, Mirabelle and Abuela argue about how her clinging to the past is hurting her family and how the pressure she puts on them is literally ripping their home and family apart:

Sight and Sightlessness in “Encanto” and “King Lear”

Perhaps the biggest connective motif between Encanto and King Lear is the motif of sight and sightlessness. Both Lear and Lord Gloucester are blind to the danger that they’re in and blind to who their real friends and enemies are. Lear trusts his two elder daughters because they flatter him, he trusts his drunken knights who only succeed in getting him forced out of the cold. Conversely, Lear ignores Cordelia. who really loves him, as well as Kent, who is a loyal nobleman to the very end, and he ignores the Fool because he’s a fool. If he had heeded any of their advice he would not have died alone and powerless. Therefore his sightlessness is a deadly weakness.

Gloucester, the other old man character in Lear has another problem with sightlessness and is punished for it figuratively and literally. Gloucester’s bastard son Edmond deceives him into thinking that his legitimate son Edgar is plotting to kill him. The old man sends Edgar away, makes Edmund his heir, and then Edmond betrays him and gets him arrested for treason.

In the play’s most savage scene, Gloucester is tortured and his eyes are literally pulled out of his head. From this moment Gloucester finally sees Edmond’s treachery, and he laments that he “Stumbled when he saw”. Gloucester feels like he is finally able to see clearly now that he is blind, not unlike the ancient Greek tragedy Oedipus Rex. Of course, nothing this gruesome can be shown in a Disney movie but the image of sight is constantly referenced in Encanto visually, and also through the lyrics of the songs. Even the name of the character; Mirabelle comes from the Spanish word ‘mira’ which means “to look”, and the first thing one might notice about her is her brightly painted green glasses, which constantly draw attention to her ability to see.

Mirabelle, like Cordelia, is able to see that her family is in pain, she sees that her family, the Encanto, and the house is in danger, while Abuela is constantly deluding herself and everybody else in thinking that nothing is wrong.

Through the course of the movie, Mirabelle is able to fix the various problems she sees. For instance, she sees that her sister Louisa is taking on too many responsibilities and refusing to admit that she is tired and feels weak. She realizes that her sister Isabella is tired of being the perfect golden child, that her Uncle Bruno is not the monster that the family declares him to be, (however catchy their song about him is).

Through her sight and her perceptiveness, Mirabelle is able to heal the wounds in her family, The last wounds that she heals are the cracks on her house, and her own Abuella’s wounds, the wounds that went deep through her and even deep through her house; she mends the problems that happened the instant that the candle came into being:

Once Mirabelle and Alma reconcile, they set about rebuilding the house in this song. Notice how many times the words “look,” and “see” are mentioned in the lyrics. Mirabelle re-iterates how each person in her family is more than their gifts, more than just the roles Abuella put them in, and they respond by telling her to look at her own gifts and be proud of who she is. She heals them by seeing them as they are, and they heal her by seeing her too.

It was when I realized this that I understood that this movie is what would have happened if King Lear had only listened to the people who really cared about him, and did not succumb to idle flattery. If only he did not let his pain and his trauma dictate the rest of his life. There’s a wonderful hopeful message here that family wounds can be healed if we take the time to see and address them. If you read King Lear and then see Encanto you can see both how these family wounds can be healed, and the tragic consequences if they are not.

I hope that this little post has helped you appreciate both works because they are both magnificent and they are both carefully constructed and they both tell a very simple lesson for all families. As families, we need to recognize our faults, forgive faults in others, and work together to mend the pain and suffering that we experience in our lives. Mirabelle and Cordelia show that we can all be heroes if we see the truth, and speak what they feel not what they ought to say.

FMI

https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeare-learning-zone/king-lear/character/analysis#king-lear

Gloucester and His Sons, PBS Learning Media: Shakespeare Uncovered: witf.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/shak15.ela.lit.gloucester/gloucester-and-his-sons-king-lears-subplot-shakespeare-uncovered/?student=true