My purpose with this post is to provide some hope and comfort by showing how Shakespeare and other Elizabethans dealt with epidemics and survived. The thing to remember is, although we are dealing with a pandemic, we are still far better prepared for it than any time in history. Furthermore, I want to draw on lessons from the past to offer hope and wisdom for people going through an epidemic.

Side note: Shakespeare refers to several diseases in his plays including “The plague,” (Bubonic Plague), “The Pox,” (syphilis), “Dropsy,” (edema), and “Falling sickness,” (epilepsy). I will mainly focus on the plague because of its strong connection to both Shakespeare’s life and career, as well as the continuing anxiety it causes to this day. I am also focusing on the plague to try and make parallels with Covid 19, a disease that, while less lethal and harder to detect, is still a pandemic that like the plague has transformed much of daily life since its inception, and could continue to grow, abate, and revive if we as a society aren’t careful.

Shakespeare’s plays also frequently allude to plagues and plague imagery, especially his most famous play, Romeo and Juliet.

First of all plague is an important plot element; an outbreak of plague prevents Romeo from getting the message that Juliet is alive, so plague inadvertently kills them both.

Plague also serves as a motif for the destructive forces that lead to the play’s tragic conclusion. After Mercutio curses “A plague on both your houses,” his death sets the events in motion that kills most of the principal the characters, as if his curse somehow infected all of them with a deadly virus.

https://www.slideshare.net/mobile/PaulHricik/the-universe-of-romeo-and-juliet-by-paul-hricik

Shakespeare exploited a unique cultural knowledge of plagues to help his audience engage with Romeo and Juliet. If you click on the link to my presentation above, you’ll see that Elizabethans believed that four liquids called humors controlled health and behavior. A humorous man was someone who was out of ballance with the humours and thus was ridiculous for failing to control his emotions. The humor choler was associated with anger and in dangerous imbalances was thought to cause terrible fevers and even plague. Hence, when characters like Romeo and Tybalt get angry, his audience knew that one way or another, that anger will kill them.

Shakespeare also uses plague as a metaphor for the hate of the two families that infects and kills the young lovers, as well as Tybalt, Paris, and Mercutio.

The play was first published in 1595, two years after a plague outbreak so bad that the theaters were all closed, so Shakespeare’s audience had a visceral reaction to this plague imagery when they saw it in the theater, especially after a year of being quarantined away from the theaters because of that exact same disease!

“Scourge and Minister”

Some of Shakespeare’s plays mention plague indirectly in relation to its perceived nature as a divine punishment. Since the very beginning of the plague,, writers, clergy, and many others perceived the plague as a divine punishment, designed to destroy the wicked, like the 10th plague in the Bible that decimated the enslaving Egyptians.

To “scourge oneself” is also a verb for whipping. In the 14th century, a group a people called the flaggelants, who voluntarily scourged themselves in the hope that God would end the disease as a result of their suffering.

Shakespeare uses both meanings of scourge in many of his plays. In Henry IV, the king is filled with remorse for usurping the throne from King Richard, and worries that his future progeny will become a scourge upon him:

I know not whether God will have it so,

For some displeasing service I have done,

That, in his secret doom, out of my blood

He’ll breed revengement and a scourge for me;

King Henry IV, Part I, Act III, Scene ii.

Sometimes a scourge is a person sent to destroy a sinful person or group of people. Shakespeare refers to the character of Richard III several times as a scourge upon the families who fought in the Wars Of The Roses.

In Shakespeare’s first cycle of four history plays, we see the families of York and Lancaster take turns usurping the throne, and committing numerous acts of murder, treason, and blasphemy. In the play that bears his name, Richard III kills the Yorkist royal family and then is murdered himself by Henry Tudor, systematically destroying the families of York and Lancaster. Thus, in Shakespeare’s propaganda version of history, he depicts Richard as a scourge who purges the throne of usurper and traitors, paving the way for the “virtuous,” Henry Tudor and his dynasty.

The Real Plague

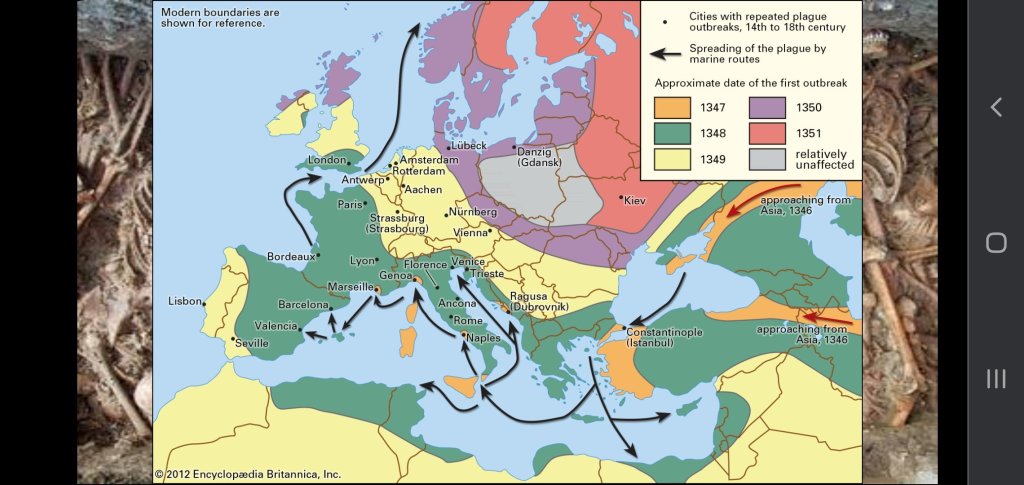

The black death, also known as Bubonic Plague, was first documented in 1347. Like Covid 19 it was first discovered in China, though it might not have originated there. Some historians argue that the Huns might have carried the plague into China and trade routes from the East carried it into Europe. By 1349 it reached England.

Everyone knew what to look for from those infected with the plague: first came fevers and chills. The next stage was the appearance of small red boils on the neck, in the armpit or groin. These lumps, were called buboes, (hence the term Bubonic Plague)

The buboes grew larger and darker in colour as the disease grew worse. From there the victim would begin to spit blood, which also contaminated with plague germs, making anyone able to spread the disease by coughing. The final stage of the illness was small, red spots on the stomach and other parts of the body caused by internal bleeding, and finally death.

We see death coming into our midst like black smoke, a plague which cuts off the young, a rootless phantom which has no mercy or fair countenance. Woe is me for the shilling in the armpit. . . It is an ugly eruption that comes with unseemly haste. It is a grievous ornament that breaks out in a rash. The early ornaments of black death.-Jevan Gethin, poet who died from plague in 1349.

John Flynn, an Irish Friar described the plague in apocalyptic terms, writing a journal for posterity, but expressed doubt that ” Any of the race of Adam would even survive.” With the horrifying spread of the epidemic, it is not hard to understand why Flynn felt that way: In 1348, there were 100,000 people living in London, but after the plague spread, the city lost 300 people every day!

https://www.google.com/amp/s/www.history.com/.amp/news/quarantine-black-death-medievalContainment/ “treatments” • Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.

• Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.

• In France, bodies were thrown in rivers (Deary)

- Quarentines: The word quarantine is Italian for 40 days. It refers to the Venetian practice of taking suspected plague victims to an island for 40 days before allowing them to enter Venice or other populated areas. The rationale was that in the Bible, the number 40 occurs many times when a person or group of people require some form of purification; the 40 days of flooding in Genesis, the 40 years that the Jews journey to the promised land, and the 40 days of fasting Christ endured before he began his ministry to name a few examples. Bubonic plague has an incubation period of less than 40 days so the quarantine actually worked- people would go to the island, then the disease would run its course and not spread out as long as it was contained. The problem was that these quarantines were also essentially leper colonies and without treatment, the infected were basically sent to die.

Social distancing in Elizabethan England–

By 1564, the year Shakespeare was born, there had been several outbreaks, but also a system designated to contain the disease. The rich went to the country. Plague bodies were burned. Theaters were closed to keep the disease from spreading. There were also body inspectors, (similar to coroner’s or death investigators today,) who inspected the bodies to look for the cause, then burned them and the clothes. Funerals for plague victims were held at night, to discourage crowds from attending, similar to our own practice of encouraging people to shop and go outside during non-peak hours.

“Treating” it: The biggest comfort I can give here is to remind people that although like the plague, we are dealing with a disease with no known cure, we still have a much better understanding of how to treat viruses than our Elizabethan forebears. Some of the “cures,” from Shakespeare’s day are downright silly, when they aren’t expensive, dangerous, and above all, ineffective.

Real plague “cures”

• Kill cats and dogs

• A poultice made of Marigold flowers and eggs

• Arsenic powder (which is highly toxic)

• Crushed emerald powder.

• Pluck a chicken and place its rear end on the patient’s buboes, known as the Vicary Method.

To bring the aftermath of the plague into a modern context, I’d like to allude to some comments from the news. Recently a few Republicans have alluded that the cost of people staying home from work would cause irreparable harm to the American economy, and alluded to the notion that a few deaths might actually benefit the economy as a whole, including Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and Republican pundit Glenn Beck.

Now at first glance these comments are gruesome and heartless, but they have a veneer of historical precedent: some people did prosper because of the black death. Laborers could charge more from their landlords simply because most of them had died, and some younger men managed to skirt the laws of primogeniture and inherit their families’ wealth because of the death of their oldest siblings. Shakespeare himself was the third child of Mary and John Shakespeare, but his elder siblings both perished due to plague. Again, to be fair to these Republicans, there is a historical facet to their arguments, however this is a very narrow and very incomplete version of history.

https://youtu.be/QNo-r20wqqg

Looking forward from the first century after the Black Death, the loss of life and resources was devastating for the workforce and caused a series of catastrophes for centuries to come. Though some peasants benefited from the lack of serfs, the depleted workforce meant work became harder and more expensive, and the coming centuries were plagued again by revolts, wars, and famine.

Just 30 years after the first outbreak of plague in England, the peasants rose in revolt against their lords for the first time in 300 years, in no small part, due to the hardships caused by the plague.

The king who punished the peasants was Richard Richard the Second, whom Shakespeare famously dramatized as an arrogant, egomaniacal, incompetent man-child who was eventually deposed and executed in the Tower of London. I think certain people who are tempted to “make sacrifices,” to protect the American economy would do well to look at this historical tragedy and avoid the political consequences of this kind of thinking.

In conclusion, though we are dealing with a frightening pandemic that we currently don’t know how to treat, we can take comfort from the fact that our forebears faced far worse diseases and survived. History has shown that social distancing works and that basic sanitation and the tireless work of healers and scientists can slow a disease, cause it to ebb, and eventually irradicate it. But until science discovers a treatment for Covid-19, it is up to all of us to flatten the curve for the sake of our country, world, and our future.

Like I have said, the working poor as a whole, suffered greatly because of the plague, especially since they were denied the means to avoid it. They lived in tightly packed, unsanitary environments and were unable to leave them without their lord’s permission, whereas we have a choice. This why it is crucial that we all do our part by staying away from crowds, observing proper hygiene, and offering support to our healthcare workers who are on the front lines of this war against coronavirus, and for whom we all pray for to stay healthy in turn.

Continue reading