Why no Coriolanus?? David Oyelowo is playing him at the National Theatre and it’s the one analysis of Shakespeare you don’t have! Please hurry! I’m seeing it on Friday!User Noittickles, sent to me today

Well, with a request like that, how can I refuse!

Coriolanus is the only Shakespearean story about Republican Rome, which is to say, before Julius Caesar turned Rome into a dictatorship. The play has been called pro-democracy, pro-monarchy, fascist, Marxist, and many other things. In some ways, the play is rather simple and its verse isn’t much fun to read, but the questions it poses, and the way Coriolanus shows the clash between power and common people, makes it fascinating to think about.

The play’s title character is also the most opaque one Shakespeare ever wrote. Some say he is a war hero, undone by the mob. Some say he is a want-to-be dictator who hates the common people and wants to keep power among the military elite. Unlike Hamlet, Macbeth, or any of Shakespeare’s other tragic heroes, we never get a sense of his true intent, or his actual feelings on anything.

To illustrate this, let’s look at two very different interpretations of the same speech. In Act III, Scene iii, the tribunes (representatives of the commons in the Senate), have organized a smear campaign to prevent Coriolanus from becoming Consul, (the highest rank a Roman aristocrat could achieve before Emperor Augustus). Coriolanus is furious at the Tribunes, and vows to leave Rome to take his revenge on the city. Here’s the text of the speech:

Coriolanus. You common cry of curs! whose breath I hate

As reek o' the rotten fens, whose loves I prize

As the dead carcasses of unburied men

That do corrupt my air, I banish you;

And here remain with your uncertainty!

Let every feeble rumour shake your hearts!

Your enemies, with nodding of their plumes,

Fan you into despair! Have the power still

To banish your defenders; till at length

Your ignorance, which finds not till it feels,

Making not reservation of yourselves,

Still your own foes, deliver you as most

Abated captives to some nation

That won you without blows! Despising,

For you, the city, thus I turn my back:

There is a world elsewhere.

[Exeunt CORIOLANUS, COMINIUS, MENENIUS, Senators,]

and Patricians]

Aedile. The people's enemy is gone, is gone!

Citizens. Our enemy is banish'd! he is gone! Hoo! hoo!

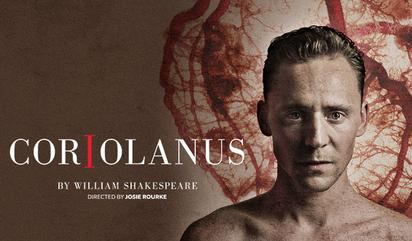

In the first speech, Tom Huddleston plays Coriolanus as a heroic soldier, disgusted and hurt by the lies of the scheming Tribunes:

Hiddleston chose to play Coriolanus not as a villain but as a frustrated demagogue- someone who wants to lead his people to greatness, whether they like it or not. Whether you approve of his methods, Hiddleston’s Caius Martius does care about the good of Rome. You can almost see the tears in his eyes as he leaves the city he loves, the city he bled for, and that has now betrayed him.

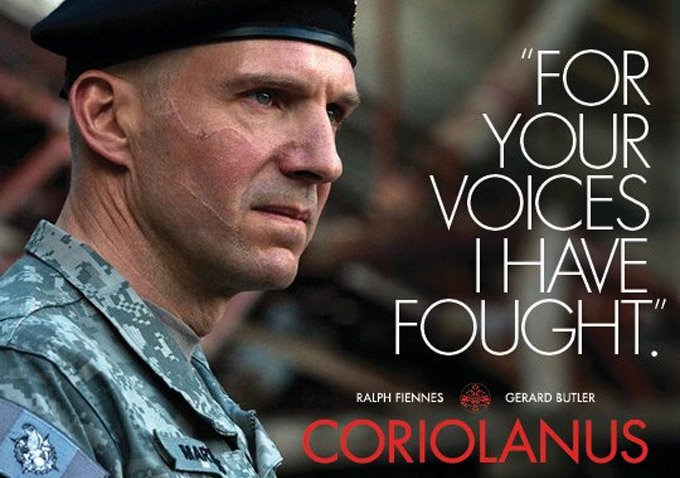

By Contrast, Ralph Fiennes takes a much more authoritarian and cruel route in the film Coriolanus, which Fiennes also directed:

Youtube critic Kyle Kallgren made the excellent case that Fiennes’ Coriolanus is first and foremost, a soldier. You could argue that perhaps Coriolanus has no political ambition whatsoever; he merely wants to keep fighting because war is all he knows. Maybe he purposefully sabotaged himself during his campaign for Consul, because all he wishes to rule is the battlefield:

Kalgren also highlights the “proto fascist” parts of Fiennes’ performance, since Fiennes himself has played Nazis, serial killers, and of course, Lord Voldemort, who is essentially a fascist dictator. Like Merchant of Venice, the Nazi party used Coriolanus as a propaganda tool, claiming that Caius’ fall from grace showed the failure of a weak democracy:

The poet deals with the problem of the people and its leader, he depicts the true nature of the leader in contrast to the aimless masses; he shows a people led in a false manner, a false democracy, whose exponents yield to the wishes of the people for egotistical reasons. Above these weaklings towers the figure of the true hero and leader, Coriolanus, who would like to guide the deceived people to its health in the same way as, in our days, Adolf Hitler would do with our beloved German Fatherland.

Martin Brunkhorst, “Shakespeare’s Coriolanus in Deutscher Bearbeitung. Quoted from Weida

It makes sense that fascists would gravitate towards a play about a seemingly virtuous Roman military leader. After all, the word “fascism” is an Italian word, coined by Benito Mussolini, to evoke the glory days of the Roman Empire- days when Roman society was based on military conquest under a strong leader. What these fascists fail to recognize is that Coriolanus is not a strong leader- he hates politics and is unable to gain any support from the people or from the elites in power. His inability to “play the game” of Roman politics, does make him appealing to some, but on the whole, his career is a disaster.

Some have chosen to interpret the story of Coriolanus as a sort of action-movie wish fulfillment- a man in a lawless society who uses his fists rather than words. Back in the 1990s, Steve Bannon (former advisor to President Donald Trump), wrote a hip-hop musical called: The Thing I Am, which re-interpreted the story of Coriolanus as a police captain who is trying to clean up downtown LA, which is embroiled in gang warfare. I find this interpretation paper-thin and not at all conducive to the spirit of the original play. It also has very racist and paternalistic undertones. You can read my review of it here:

Coriolanus Today

https://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/productions/coriolanus/

Shakespeare refuses to be prescriptive on political or social issues. He tries to represent all sides of an issue and let the audience decide. With the rise of neo-fascist movements, sectarian violence, and the persistent questions surrounding police and military forces, Coriolanus is more relevant than ever. I haven’t seen this production at the National Theater, but I hope it calls attention to the various angles and points of view of the play- Coriolanus the war hero, Coriolanus the traitor, Coriolanus the soldier, Coriolanus the would-be-dictator. David Oyelowo is a fantastic Shakespearean actor, so I’m sure he can bring a great deal of complexity and nuance to this complicated man.

What I find interesting is that the trailer chooses to use this speech, when Coriolanus has defected to Rome’s enemies, the Volskies. He seems sorrowful, desperate, and afraid of what the Volskies will do to him, now that he is in their camp. One line that Oyelowo delivered exceptionally well was the line “Only the name remains.” I haven’t seen the whole play, but it seems THIS Coriolanus is concerned with the glory of his name living after him. The final question this play asks is, for such a complicated man, how will Coriolanus be remembered?

Well, there you go, Stopittickles! Hope you enjoyed this overview of the play Coriolanus. If you like this review, you might like to sign up for my online class on Julius Caesar via outschool.com:

Click here to sign up and get a $5 discount: https://outschool.com/teachers/The-Shakespearean-Student