Watch “Gladius – The Sword That Conquered the World” on YouTube

Julius Caesar’s success as a politician was deeply tied to his success as a military leader. Therefore studying the Roman army during Caesar’s life helps one understand why he was so popular and why the Senate wanted him dead.

Caesar was commander (or legatus legionis) of the 10th mounted legion, which means his soldiers were mounted on horseback. Caesar was in charge of maintaining control over the warring tribes in Gaul (modern day France). Each legion was organized into 6 companies (cohorts) of 100 men, led by a Centurian, Source : http://thedioscuricollection.com/ejercito_romano_en.php

According to Imperiumromium.com, Caesar helped reform his army, and his Centurians carried out many different campaigns in Gaul:

As you can see, his soldiers were mainly armed with helmets, leather armor, and their large shields and Gladius swords. Below is an exploration of the different parts of the Roman uniform:

https://costumes.lovetoknow.com/roman-soldier-uniform

I’ve seen four live productions of Romeo and Juliet, (5 if you include West Side Story). I’ve also watched four films (6 if you include West Side Story and Gnomio and Juliet) and one thing that I’ve noticed again and again, and again is that you can tell the whole story of the play with clothing. This is a story about families who are part of opposite factions whose children secretly meet, marry, die, and fuse the families into one, and their clothes can show each step of that journey.

The feud

Nearly every story about a conflict or war uses contrasting colors to show the different factions. Sometimes even real wars become famous for the clothes of the opposing armies. The Revolutionary War between the redcoats and the blue and gold Continentals, the American Civil War between the Rebel Grays and the Yankee Bluebellies. In almost every production I’ve ever seen, the feud in Romeo and Juliet is also demonstrated by the opposing factions wearing distinctive clothing.

Historically, warring factions in Itally during the period the original Romeo and Juliet is set, wore distinctive clothes and banners as well. . In this medieval drawing, you can see Italians in the Ghibelline faction, who were loyal to the Holy Roman Empire, fighting the Guelph faction (red cross), who supported the Pope. Powerful families were constantly fighting and taking sides in the Guelf vs. ghibelines conflict in Verona, which might have inspired the Capulet Montegue feud in Romeo and Juliet.

Even the servants of the nobles got roped into these conflicts, and they literally wore their loyalties on their sleeves. The servants wore a kind of uniform or livery to show what household they belonged to. The servants Gregory and Sampson owe their jobs to Lord Capulet, and are willing to fight to protect his honor. Perhaps Shakespeare started the play with these servants to make this distinction very obvious. Here’s a short overview on Italian Liveries from the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/86582

In 1966, director Franco Zepherelli set a trend with his iconic use of color in his movie. He chose to make the Capulets wear warm tones while the Montegues wore blue and silver. Juliet (Olivia Hussey) wore a gorgeous red dress that made her look youthful, passionate, and lovely, while Tybalt (Michael York), wore red, orange, and black to emphasize his anger, and jealousy (which has been associated for centuries with the color orange). By contrast, the Montagues like Romeo (Leonard Whiting) wore blue, making him look peaceful and cool. These color choices not only clearly indicate who belongs to which contrasting factions, but also help telegraph the character’s personalities. Look at the way these costumes make the two lovers stand out even when they’re surrounded by people at the Capulet ball:

Zepherilli’s color choices were most blatantly exploited in the kids film Gnomio and Juliet, where they did away with the names Capulet and Montegue altogether, and just called the two groups of gnomes the Reds and the Blues.

The Dance

To get Romeo and Juliet to meet and fall in love, Shakespeare gives them a dance scene for them to meet and fall in love. He further makes it clear that when they first meet, Romeo is in disguise. The original source Shakespeare used made the dance a carnival ball, (which even today is celebrated in Italy with masks). Most productions today have Romeo wearing a mask or some other costume so that he is not easily recognizable as a Montague. Masks are a big part of Italian culture, especially in Venice during Carnival:

In the 1996 movie, Baz Luhrman creates a bacchanal costume party, where nobody wears masks but the costumes help telegraph important character points. Mercutio is dressed in drag, which not only displays his vibrant personality but also conveniently distracts everyone from the fact that Romeo is at the Capulet party with no mask on.

Capulet is dressed like a Roman emperor, which emphasizes his role as the patriarch of the Capulet family. Juliet (Claire Danes) is dressed as an angel, to emphasize the celestial imagery Shakespeare uses to describe her. Finally, Romeo (Leonardo DiCaprio) is dressed as a crusader knight because of the dialogue in the play when he first meets Juliet:

Romeo. [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this:720

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Juliet. Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims' hands do touch,725

And palm to palm is holy palmers' kiss.

Romeo. Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too?

Juliet. Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer.

Romeo. O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do;

They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair.730

Juliet. Saints do not move, though grant for prayers' sake.

Romeo. Then move not, while my prayer's effect I take.

Thus from my lips, by yours, my sin is purged.

Juliet. Then have my lips the sin that they have took.

Romeo. Sin from thy lips? O trespass sweetly urged!735

Give me my sin again.

Juliet. You kiss by the book. Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene V, Lines 719-737.

Notice that Romeo calls Juliet a saint, and later an angel in the famous balcony scene, which explains her costume at the ball. Juliet refers to Romoe as a Pilgrim, which is a cheeky comment on his crusader knight costume. In the Crusades, crusader knights made pilgrimages to the holy land, with the hope that God (and presumably, his angels) would forgive their sins. Romeo’s name even means “Pilgrim.” Luhrman makes clever nods to Shakespeare’s text by dressing Romeo and Juliet in this way, and gives the dialogue a bit of a playful roleplay as the characters make jokes about each other’s costumes- Romeo hopes that he will go on a pilgrimage and that this angel will take his sin with a kiss.

In Gnomio and Juliet, the titular characters meet in a different kind of disguise. Rather than going to a dance with their family, they are both simultaneously trying to sneak into a garden and steal a flower, so they are both wearing black, ninja-inspired outfits. Their black clothing helps them meet and interact without fear of retribution from their parents (since they do not yet know that they are supposed to be enemies. The ninja clothes also establishes that for these two gnomes, love of adventure unites them. Alas though, it doesn’t last; Juliet finds out that Gnomio is a Blue, when they both accidentally fall in a pool, stripping their warpaint off and revealing who they are.

Sometimes the dance shows a fundamental difference between the lovers and the feuding factions. West Side Story is a 20th-century musical that re-imagines the feuding families as juvenile street gangs, who like their Veronese counterparts, wear contrasting colors. The Jets (who represent the Montagues) wear Blue and yellow, while the Sharks (Capulets), wear red and black. The gang members continue wearing these colors on the night of the high school dance, except for Tony and Maria (the Romeo and Juliet analogs). In most productions I’ve seen, (including the 2021 movie), these young lovers wear white throughout the majority of the play, to emphasize the purity of their feelings, and their rejection of violence. Thus, unlike Shakespeare’s version of the story, West Side Story makes the lovers unquestionably purer are more peaceful than Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, and their clothing makes this clear.

The Merging of the family

(8:30-11:00)

Costume Designer Charlene in the 2006 AU production deliberately had the characters change clothes when they get married. Juliet was wearing the same iconic red dress as Olivia Hussey for the first two acts of the play but then changed into a pale blue gown that matches Romeo. The clothes re-enforce the idea that the marriage represents Romeo and Juliet abandoning their family’s conflicts, and simply showing their true colors.

Another way of getting everyone in the family to subconsciously unite in grief would be to costume everyone wearing black except Romeo and Juliet. At the end of the play, The Capulets are already mourning Juliet, (because she faked her death in Act IV), and the Montegues are already mourning Lady Montegue (who died offstage). Just by these circumstances, everyone could come onstage wearing black, uniting in their grief, which is further solidified when they see their children dead onstage.

Not all productions choose to costume the characters like warring factions, but nevertheless, any theatrical production’s costumes must telegraph something about the characters. In these production slides for a production I worked on in 2012, the costumes reflect the distinct personality of each character and show a class difference between the Montagues and the Capulets.

The 2013 Film: Costumes Done Badly

The 2013 movie is more concerned with showing off the beauty of the actor’s faces, and the literal jewels than the clothes:

Most of the actors and costumes are literally in the dark for most of the film, probably because the film was financed by the Swarofski Crystal company, who literally wanted the film to sparkle. Ultimately, like most jewelry, I thought the film was pretty to look at, but the costumes and cinematography had little utilitarian value. The costumes and visual didn’t tell the story efficiently, but mainly was designed to distract the audience with the beauty of the sets, costumes and the attractive young actors. The only thing I liked was a subtle choice to make Juliet’s mask reminiscent of Medusa, the monster in Greek Myth, who could turn people to stone with a look. I liked that the film was subtly implying that love, at first sight, can be lethal.

If you enjoyed this video, please consider signing up for my online class, “Basics Of Stage Combat,” on Outschool.com: https://outschool.com/classes/basics-of-stage-combat-pUrfWBtA?usid=MaRDyJ13&signup=true&utm_campaign=share_activity_link

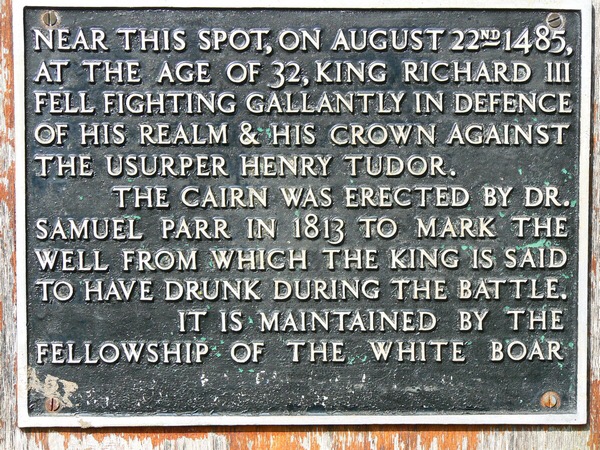

To begin wrapping up our Richard III month, I thought it might be appropriate to speak a little about the battle that ended the real Richard’s life, the Battle of Bosworth Field, August 22, 1485.

What does Shakespeare Say about the battle:

KING RICHARD III

Come, bustle, bustle; caparison my horse.

Call up Lord Stanley, bid him bring his power:

I will lead forth my soldiers to the plain,

And thus my battle shall be ordered:

My foreward shall be drawn out all in length,

Consisting equally of horse and foot;

Our archers shall be placed in the midst

John Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Earl of Surrey, Shall have the leading of this foot and horse. They thus directed, we will follow In the main battle, whose puissance on either side Shall be well winged with our chiefest horse. This, and Saint George to boot!

What think’st thou, Norfolk?

NORFOLK

A good direction, warlike sovereign.

Richard III, Act V, Scene iii.

This speech matches very well with what the chronicles mention about the battle. In those days the English archers were more deadly than their cavalry, so Richard probably wanted to pick off as many soldiers as possible with the archers, then mow the rest down with his charge toward Henry.

Contemporary Accounts, (courtesy of the Richard III Society). The most complete, and unbiased account I could find was Polydore Virgil, which is also likely the one from which Shakespeare got his information. You’ll notice that it mentions the long line of foot soldiers and horsemen, and the mention of the Duke of Norfolk commanding one of Richard’s forces.

‘The day after King Richard, well furnished in all things, drew his whole army out of their encampments, and arrayed his battle-line, extended at such a wonderful length, and composed of footmen and horsemen packed together in such a way that the mass of armed men struck terror in the hearts of the distant onlookers. In the front he placed the archers, like a most strong bulwark, appointing as their leader John, duke of Norfolk. To the rear of this long battle-line followed the king himself, with a select force of soldiers.‘Meanwhile … early in the morning [Henry Tudor] commanded his soldiery to set to arms, and at the same time sent to Thomas Stanley, who now approached the place of the fight, midway between the two armies, to come in with his forces, so that the men could be put in formation. He answered that Henry should set his own men in line, while he would be at hand with his army in proper array. Since this reply was given contrary to what was expected, and to what the opportunity of the time and greatness of the cause demanded, Henry became rather anxious and began to lose heart. Nevertheless without delay he arranged his men, from necessity, in this fashion. He drew up a simple battle-line on account of the fewness of his men. In front of the line he placed archers, putting the earl of Oxford in command; to defend it on the right wing he positioned Gilbert Talbot, and on the left wing in truth he placed John Savage. He himself, relying on the aid of Thomas Stanley, followed with one company of horsemen and a few foot-soldiers. For all in all the number of soldiers was scarcely 5,000, not counting the Stanleyites of whom about 3,000 were in the battle under the leadership of William Stanley. The king’s forces were at least twice as many.

‘Thus the battle-line on each side was arrayed. As soon as the two armies came within sight of each other, the soldiers donned their helms and prepared for the battle, waiting for the signal to attack with attentive ears. There was a marsh between them, which Henry deliberately left on his right, to serve his men as a defensive wall. In doing this he simultaneously put the sun behind him. The king, as soon as he saw the enemy advance past the marsh, ordered his men to charge. Suddenly raising a great shout they attacked first with arrows, and their opponents, in no wise holding back from the fight, returned the fire fiercely. When it came to close quarters, however, the dealing was done with swords.‘In the mean time the earl of Oxford, afraid that in the fighting his men would be surrounded by the multitude, gave out the order through the ranks that no soldier should go more than ten feet from the standards.

‘Thus the battle-line on each side was arrayed. As soon as the two armies came within sight of each other, the soldiers donned their helms and prepared for the battle, waiting for the signal to attack with attentive ears. There was a marsh between them, which Henry deliberately left on his right, to serve his men as a defensive wall. In doing this he simultaneously put the sun behind him. The king, as soon as he saw the enemy advance past the marsh, ordered his men to charge. Suddenly raising a great shout they attacked first with arrows, and their opponents, in no wise holding back from the fight, returned the fire fiercely. When it came to close quarters, however, the dealing was done with swords.‘In the mean time the earl of Oxford, afraid that in the fighting his men would be surrounded by the multitude, gave out the order through the ranks that no soldier should go more than ten feet from the standards.

When in response to the command all the men massed together and drew back a little from the fray, their opponents, suspecting a trick, took fright and broke off from the fighting for a while. In truth many, who wished the king damned rather than saved, were not reluctant to do so, and for that reason fought less stoutly. Then the earl of Oxford on the one part, with tightly grouped units, attacked the enemy afresh, and the others in the other part pressing together in wedge formation renewed the battle.

While the battle thus raged between the front lines in both sectors, Richard learnt, first from spies, that Henry was some way off with a few armed men as his retinue, and then, as the latter drew nearer, recognised him more certainly from his standards. Inflamed with anger, he spurred his horse, and road against him from the other side, beyond the battle line. Henry saw Richard come upon him, and since all hope of safety lay in arms, he eagerly offered himself for this contest. In the first charge Richard killed several men; toppled Henry’s standard, along with the standard-bearer William Brandon; contended with John Cheney, a man of surpassing bravery, who stood in his way, and thrust him to the ground with great force; and made a path for himself through the press of steel.

‘Nevertheless Henry held out against the attack longer than his troops, who now almost despaired of victory, had thought likely. Then, behold, William Stanley came in support with 3,000 men. Indeed it was at this point that, with the rest of his men taking to their heels, Richard was slain fighting in the thickest of the press. Meanwhile the earl of Oxford, after a brief struggle, likewise quickly put to flight the remainder of the troops who fought in the front line, a great number of whom were killed in the rout. Yet many more, who supported Richard out of fear and not out of their own will, purposely held off from the battle, and departed unharmed, as men who desired not the safety but the destruction of the prince whom they detested. About 1,000 men were slain, including from the nobility John duke of Norfolk, Walter Lord Ferrers, Robert Brackenbury, Richard Radcliffe and several others. Two days after at Leicester, William Catesby, lawyer, with a few associates, was executed. Among those that took to their heels, Francis Lord Lovell, Humphrey Stafford, with Thomas his brother, and many companions, fled into the sanctuary of St. John which is near Colchester, a town on the Essex coast. There was a huge number of captives, for when Richard was killed, all men threw down their weapons, and freely submitted themselves to Henry’s obedience, which the majority would have done at the outset, if with Richard’s scouts rushing back and forth it had been possible. Amongst them the chief was Henry earl of Northumberland and Thomas earl of Surrey. The latter was put in prison, whree he remained for a long time, the former was received in favour as a friend at heart. Henry lost in the battle scarcely a hundred soldiers, amongst whom one notable was William Brandon, who bore Henry’s battle standard. The battle was fought on the 11th day before the kalends of September, in the year of man’s salvation 1486, and the struggle lasted more than two hours.

‘The report is that Richard could have saved himself by flight. His companions, seeing from the very outset of the battle that the soldiers were wielding their arms feebly and sluggishly, and that some were secretly deserting, suspected treason, and urged him to flee. When his cause obviously began to falter, they brought him a swift horse. Yet he, who was not unaware that the people hated him, setting aside hope of all future success, allegedly replied, such was the great fierceness and force of his mind, that that very day he would make an end either of war or life. Knowing for certain that that day would either deliver him a pacified realm thenceforward or else take it away forever, he went into the fray wearing the royal crown, so that he might thereby make either a beginning or an end of his reign. Thus the miserable man suddenly had such an end as customarily befalls them that for justice, divine law and virtue substitue wilfulness, impiety and depravity. To be sure, these are far more forcible object-lessons than the voices of men to deter those persons who allow no time to pass free from some wickedness, cruelty, or mischief.

‘Immediately after gaining victory, Henry gave thanks to Almighty God with many prayers. Then filled with unbelievable happiness, he took himself to the nearest hill, where after he had congratulated his soldiers and ordered them to care for the wounded and bury the slain, he gave eternal thanks to his captains, promising that he would remember their good services. In the mean time the soldiers saluted him as king with a great shout, applauding him with most willing hearts. Seeing this, Thomas Stanley immediately placed Richard’s crown, found among the spoil, on his head, as though he had become king by command of the people, acclaimed in the ancestral manner; and that was the first omen of his felicity.’

-Polydore Virgil, c. 1500. Reprinted from the Richard III Society:

http://www.r3.org/richard-iii/the-battle-of-bosworth/bosworth-contemporary-tudor-accounts/

What most people can agree:

Above- infographic of Richard’s battle wounds, courtesy of Lifescience.com

To conclude, even Shakespeare admits that Richard was a great commander, who lost the battle when his own soldiers betrayed him, and he was piteously murdered by the man who took over the crown from him. It’s a good thing that the real King Richard’s remains were discovered in 2012, and we now know more about the real man in addition to the myth.

RIP Richard.

Hi everyone,

Introducing our new Play of the Month: Shakespeare’s dark history play about murder and corruption, Richard III. First, a short presentation I made that introduces the characters and themes of the play.

Second, a quick, funny summary of the play from the Reduced Shakespeare Company