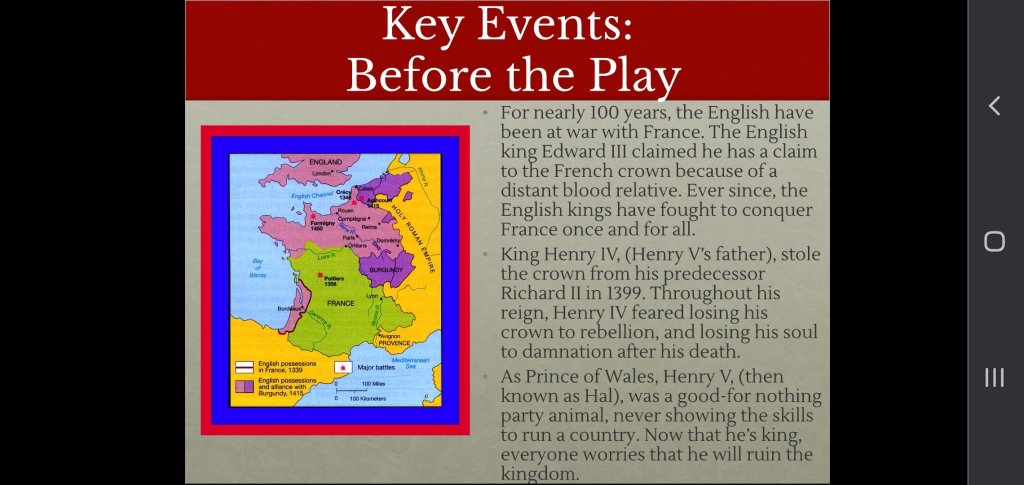

Though Shakespeare’s Hamlet is very much the story of a renaissance prince, it’s important to remember that the play’s sources date back to the Dark Ages. The anonymous “UR-Hamlet,” (later published in the early 1590s ), is based on an ancient legend about a prince who fights to the death to revenge his father’s murder. Shakespeare’s adaptation still contains a nod to this ancient culture that praised and highly ritualized the concept of judicial combat.

Back in Anglo-Saxon times, private disputes, (such as the murder of one’s father) could be settled through means of a duel. In this period, England was occupied by the Danes, (which we would now call Vikings), and several Viking practices of judicial combat survive. For example, the Hólmgangan, an elaborate duel between two people who fight within the perimeter of a cloak.

At the end of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, the revenge cycle between Hamlet, Leartes, and Fortinbras, comes to a close using a duel. Hamlet has murdered Leartes’ father but Hamlet did not intentionally kill him. This kind of legal dispute would certainly have been settled with a duel in Saxon times. This is one reason why Leartes scorns Hamlet’s offer of forgiveness at the beginning of the scene, and instead trusts in the outcome of the fight to prove his cause. Hamlet and Leartes begin fighting officially under the terms of a friendly fencing match, but it becomes clear early on that at least in the mind of Leartes, this is actually a blood-combat. He is demanding blood for the death of his father, as the Danes would have done during the Anglo Saxon times when Shakespeare’s source play of Hamlet was written.

What happens in the fight

The sword fight at the end of Hamlet is surprising in many ways. First of all, it is much more choreographed than many of Shakespeare’s other fights which are usually dramatized on the page very simply with two words: “They fight.” In Hamlet by contrast, Shakespeare has a series of important and descriptive stage directions. Furthermore, the fight is divided into three distinct bouts or phrases, or if you like “mini fights.” Below is the full text of the fight. I shall then explain what happens in each phrase.

PHrase One

Shakespeare it very clear that Hamlet gets a normal fencing rapier, while Leartes gets a sharp one, they fight one fencing bout where Hamlet scores a point. This is the most “sportsman like” part of the fight:

Enter King, Queen, Laertes, Osric, and Lords, with other Attendants with foils and gauntlets. A table and flagons of wine on it. Claudius. Come, Hamlet, come, and take this hand from me. [The King puts Laertes' hand into Hamlet's.] Hamlet. Give me your pardon, sir. I have done you wrong; But pardon't, as you are a gentleman. Laertes. I am satisfied in nature, Whose motive in this case should stir me most To my revenge. But till that time I do receive your offer'd love like love, And will not wrong it.3890 Hamlet. I embrace it freely, And will this brother's wager frankly play. Give us the foils. Come on. Laertes. Come, one for me. Hamlet. I'll be your foil, Laertes. In mine ignorance3895 Your skill shall, like a star i' th' darkest night, Stick fiery off indeed. Laertes. You mock me, sir. Hamlet. No, by this hand. Claudius. Give them the foils, young Osric. Cousin Hamlet,3900 You know the wager? Hamlet. Very well, my lord. Your Grace has laid the odds o' th' weaker side. Claudius. I do not fear it, I have seen you both; But since he is better'd, we have therefore odds.3905 Laertes. This is too heavy; let me see another. Hamlet. This likes me well. These foils have all a length? They Prepare to play. Osric. Ay, my good lord. Claudius. Set me the stoups of wine upon that table.3910 If Hamlet give the first or second hit, Or quit in answer of the third exchange, Let all the battlements their ordnance fire; The King shall drink to Hamlet's better breath, And in the cup an union shall he throw3915 Richer than that which four successive kings In Denmark's crown have worn. Give me the cups; And let the kettle to the trumpet speak, The trumpet to the cannoneer without, The cannons to the heavens, the heaven to earth,3920 'Now the King drinks to Hamlet.' Come, begin. And you the judges, bear a wary eye. Hamlet. Come on, sir. Laertes. Come, my lord. They play. Hamlet. One.3925 Laertes. No. Hamlet. Judgment! Osric. A hit, a very palpable hit. Laertes. Well, again! Claudius. Stay, give me drink. Hamlet, this pearl is thine;3930 Here's to thy health. [Drum; trumpets sound; a piece goes off [within].] Give him the cup. Hamlet. I'll play this bout first; set it by awhile.

Phrase Two

- Claudius. Come. [They play.] Another hit. What say you?3935

- Laertes. A touch, a touch; I do confess’t.

- Claudius. Our son shall win.

- Gertrude. He’s fat, and scant of breath.

Here, Hamlet, take my napkin, rub thy brows.

The Queen carouses to thy fortune, Hamlet.3940 - Hamlet. Good madam!

- Claudius. Gertrude, do not drink.

- Gertrude. I will, my lord; I pray you pardon me. Drinks.

- Claudius. [aside] It is the poison’d cup; it is too late.

- Hamlet. I dare not drink yet, madam; by-and-by.3945

- Gertrude. Come, let me wipe thy face.

- Laertes. My lord, I’ll hit him now.

- Claudius. I do not think’t.

- Laertes. [aside] And yet it is almost against my conscience.

Again, Hamlet gets the upper hand and scores a point. While his mother is celebrating his victory, she accidently drinks the poisoned cup that Claudius meant for Hamlet. Now Claudius is enraged, Laertes is angry because of losing the first two bouts, and Hamlet is blissfully unaware that he is in mortal danger.

Phrase Three

When Hamlet isn’t expecting it, Leartes wounds him with the poisoned sword. From there, the fight degenerates into a violent, bloody mess where Hamlet disarms Laertes, then stabs Leartes. After this, the Queen dies, and Hamlet kills Claudius:

- Hamlet. Come for the third, Laertes! You but dally.3950

Pray you pass with your best violence;

I am afeard you make a wanton of me. - Laertes. Say you so? Come on. Play.

- Osric. Nothing neither way.

- Laertes. Have at you now!3955

[Laertes wounds Hamlet; then] in scuffling, they change rapiers, [and Hamlet wounds Laertes].

- Claudius. Part them! They are incens’d.

- Hamlet. Nay come! again! The Queen falls.

- Osric. Look to the Queen there, ho!

- Horatio. They bleed on both sides. How is it, my lord?3960

- Osric. How is’t, Laertes?

- Laertes. Why, as a woodcock to mine own springe, Osric.I am justly kill’d with mine own treachery.

- Hamlet. How does the Queen?

- Claudius. She sounds to see them bleed.

- Gertrude. No, no! the drink, the drink! O my dear Hamlet!3965

The drink, the drink! I am poison’d. [Dies.] - Hamlet. O villany! Ho! let the door be lock’d.

Treachery! Seek it out.

- Laertes. It is here, Hamlet. Hamlet, thou art slain;3970

No medicine in the world can do thee good.

In thee there is not half an hour of life.

The treacherous instrument is in thy hand,

Unbated and envenom’d. The foul practice

Hath turn’d itself on me. Lo, here I lie,3975

Never to rise again. Thy mother’s poison’d.

I can no more. The King, the King’s to blame. - Hamlet. The point envenom’d too?

Then, venom, to thy work. Hurts the King. - All. Treason! treason!3980

- Claudius. O, yet defend me, friends! I am but hurt.

- Hamlet. Here, thou incestuous, murd’rous, damned Dane,

Drink off this potion! Is thy union here?

Follow my mother. King dies.

God’s providence in Hamlet (or lack therEof)

It is telling that everyone dies in this scene, which indicates that the concept of providence seems somewhat ambiguous in this scene- yes, Claudius dies but so does Hamlet. In addition, Leartes dies justly for his own treachery as he claims, but he also tries to avoid damnation. Leartes is guilty of treason for killing Hamlet, but Hamlet is guilty of killing an old man and a young maid, so Leartes asks God to forgive Hamlet for two murders, while he has only committed one. Providence doesn’t seem clear which crimes are worse. Further, Providence fails to reveal the guilt or innocence of Queen Gertrude- did she know her second husband murdered her first? Did she support Hamlet’s banishment? Did she know the cup was poisoned, and is therefore guilty of suicide, or was she ignorant and punished by fate for her adultery and incest? Knowing the conventions of judicial combat help the reader understand the compex world of Hamlet, a world devoid of easy answers.

How Would I Stage the Fight?

Phrase 1

I want the two combatants to start en guarde, their blades touching, then there will be a series of attacks on the blade.

Hamlet will advance and attack the low line of Leartes’ sword

Hamlet will advance and attack the high line of Leartes’ sword

Leartes will advance and beat attack the high line of Hamlet’s sword

Leartes will advance and attack the low line of Hamlet’s sword

Hamlet performs a bind on Leartes’ sword, sending it off on a diagonal high line.

Hamlet attacks Leartes leg and Leartes will react in mild pain.

Phrase 2

Leartes is no longer fighting in polite manner, so this will be the real fight where he’s actually going for targets

Hamlet and Leartes come together and bow,

Both go into en guarde and Osric signals the start of the fight.

Hamlet attacks Leartes’ blade high

Leartes attacks Hamlet’s blade low

Leartes suddenly does a moulinet and attacks Hamlet’s right arm. Hamlet does a pass back and parries 3

Leartes attacks Hamlet’s Left Arm. Hamlet does another pass back and parries 4

Leartes cuts for Hamlet’s head. Hamlet passes back and does a hanging parry 6, which causes the sword to slide off.

Hamlet ripostes, slips around Leartes’ ________side, and thrusts offline in suppination. He then flicks the sword, hiting the back of Leartes’ knee.

Phrase 3

Concern- you need to have enough space for Hamlet to chase Leartes DS, and for Leartes to slice Hamlet with the forte of his sword.

Before the bout is supposed to start, Hamlet walks toward the sword, point down to Leartes US L or USR

“I am afeard you make a wanton of me”

Leartes: “You mock me sir!”

Hamlet: “No, by this hand”

Hamlet presents his hand. Leartes places his sword on it, and slices it

Leartes gives Hamlet a stomach punch

Hamlet falls to his knees dropping the sword. If necessary, Hamlet can pull out a blood pack to put on his hand.

Leartes points his blade above Hamlet’s head, then brings it back, preparing to strike off Hamlet’s head.

Leartes: “Have at you now”

Hamlet ducks to the right, with his leg extended.

Leartes Passes forward, trips on Hamlet’s leg. Hamlet does a slip and goes behind Leartes’ back.

Hamlet rabbit punches Leartes on the back, picks up Leartes’ sword, noticing the blood on it

Leartes slowly rises, then notices Hamlet with his sword, he quickly grabs Hamlet’s weapon

Hamlet shoves Leartes DS into a corp a corp, then traps Leartes’ blade

The two push each other for a while

Osric: “Nothing Neither way”

Hamlet pushes Leartes downstage, then slices him across the back.

Leartes stops DS, and falls to the ground

Murder of Claudius

If Claudius is standing, we can have Horatio grab the king around the neck, Hamlet places the sword across Claudius’ stomach, and slices him.

If Claudius is seated, Hamlet picks up the goblet with one hand, slices the king’s leg, then, (after establishing a good distance), Hamlet points the blade off line, just left of Claudius’ neck. Hamlet is giving Claudius a choice- drink or be stabbed. When Claudius chooses to drink, either Hamlet or Horatio can give him the cup. If Horatio gives it to Claudius, it might give him the idea to die later.

Sources:

Sources-

- Ur- Hamlet

- Lear source- Hollinshed’s Chronicles

- Holm ganner

- JSTOR

- Dr. Cole

- Bf paper on duels

- Tony Robinson’s Crime and Punishment: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2yz9VLkNHJU&feature=youtu.be

- Truth Of the Swordhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vFL2ghH0RLs

- Secrets Of the VIking Sword http://youtu.be/nXbLyVpWsVM

- Ancient Inventions- War and Conflict http://youtu.be/IuyztjReB6A

- Terry Jones- Barbarians (the Savage Celts) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSuizSkHpxI

- Joe Martinez book

If you enjoyed this post, and would like to do some stage combat of your own, sign up for one of my stage combat classes on Outschool.com!