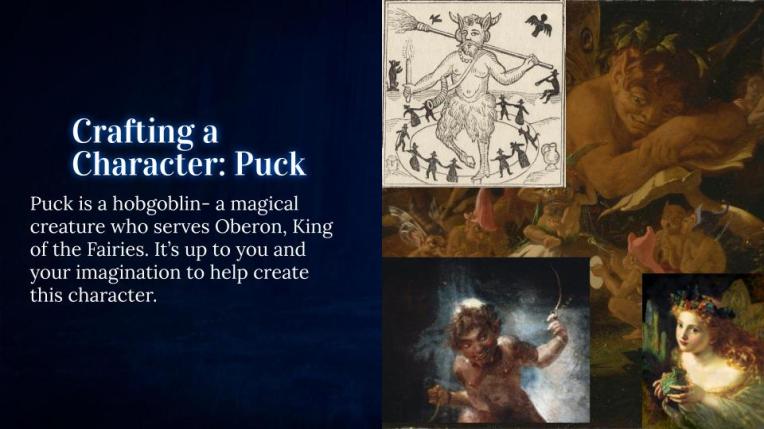

Was Shakespeare racist? When reading Othello by William Shakespeare, the only play he wrote where the hero is explicitly black, I truly feel like the Shakespearean student as opposed to the Shakespearean teacher. it’s a play that I find very difficult to get into, and very difficult to understand. Above all, the question I have is whether Othello is a positive or negative portrayal of a black man. So I am going to analyze the play, the prevailing views about race from Shakespeare’s time, and try to draw some conclusions about the play and its creator.

Disclaimer: I don’t advocate trying to speculate about how Shakespeare felt about anything. My real point in this post is to determine if the play Othello and its portrayal of people of color, has merit in today’s society, which is important to establish given the culture in which Shakespeare wrote it.

Part I: Black People And Shakespeare

By our standards, Shakespeare was probably racist. If you look at the ways black people are mentioned in documents of the period, the writers frequently describe black people with an air of otherness and superiority that shows little interest in the humanity of other races. In fact, one reason why the word “moor” is so problematic is that it basically referred to anyone not born in Europe. It could refer to people from Northern Africa, the Middle East, and even parts of Spain. Clearly, Europeans at the time weren’t interested in the particulars of their non-Caucasian neighbors’ culture and herritage.

This is not to say that Shakespeare never knew any black people. Michael Wood in his book In Search Of Shakespeare estimates that there might have been several thousand black people in London alone. City registers mentions not only black people employed in the city, but even some of the first inter-racial marriages. Therefore, the notion of Othello marrying Desdemona would not have been unheard of even in 1601.

As an important note, the black people living in Europe at the time weren’t slaves. The transatlantic slave trade didn’t really get started in and America until the 1650s, and slavery was illegal in England at the time. Wood mentions that there were black dancers, black servants, and other free black people living in and around London (Wood 25). Dr. Matthieu Chapman wrote an excellent thesis back in 2010 about the possibility that some black people might even have been actors in Shakespeare’s company. Furthermore, scholars have wondered for centuries if the Dark Lady of the sonnets was Shakespeare’snon-Caucasian mistress.

In any case, it is likely based on what we know about the growing multiculturalism of England in the 17th century, that Shakespeare knew some black people, and might have worked along side them. Though Shakespeare probably knew black people though, it is impossible to know if they influenced his play Othello.

https://youtu.be/NsUoW9eNTAw

Though black people were allowed to live and work without bondage, their lives were highly precarious, and far from easy. In 1601, Sir Robert Cecil, Queen Elizabeth’s chief counselor, presented a plan to explel all black people from England (Wood 251). The Cecil Papers at Hatfield House details that:

The queen is discontented at the great numbers of ‘n—‘ and ‘blackamoores’ which are crept into the realm since the troubles between her highness and the King Of Spain, and are fostered here to the annoyance of her own people.

Cecil mentions that a great deal of black people living in London were former slaves freed from captured Spanish ships. Spain of course was Catholic and their king Phillip II had sent a vast armada against the English which helps underscore a major reason for the hostility against these formerly Spanish moors; the fear that, even though these people were baptized English Christians, they might secretly be traitors, sympathetic to the Spanish or to the great numbers of Muslims living in Spain. The English weren’t the only ones concerned. In 1609, the Spanish king expelled the Moors from Spain entirely, probably due to the high levels of Muslims in Spain. With this in mind, you can see how topical Othello was for its time, since it touched on many contemporary issues of race and politics.

One important thing to remember about Othello is that he is not only a black man in a predominantly white country, he is in all probability a converted Muslim who helps the Venetian army fight Muslim Turks. With this in mind, you can imagine how hard it must be for the people of Venice to trust him, and how hard it makes it for Othello to feel like a true Venetian.

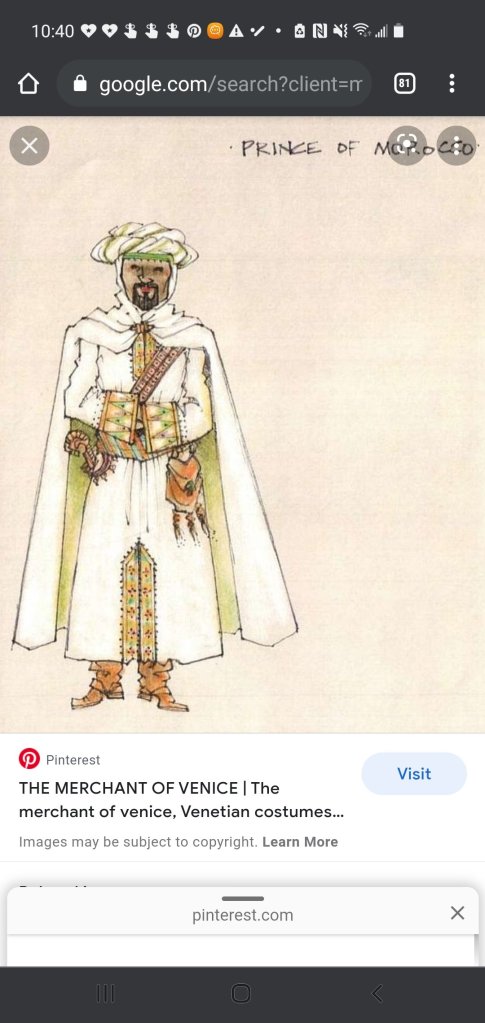

A very high profile example of the mixture of admiration and anxiety towards Moors comes from 1600. Ambassador Abdul Guahid from Morocco, (himself a Moor), came to visit London to discuss a military plan to take the East and West Indes away from the Spanish. He stayed at the court for several months during which time, Shakespeare’s company performed for him and the court. To commemorate the visit, a writer called Leo the African presented the ambassador with a book called A Geographical History Of Africa, and he himself posed for a portrait, shown below.

![]()

![]()

Most scholars cite Guahid as one of the likely inspirations for Othello’s character. Some even suggest that Othello’s original costume and appearance might have been taken from Guahid. Although he was honored publicly, according to the documentary Shakespeare Uncovered, in private, courtiers were whispering about Guahid, hoping that he would leave England soon. Whether Guahid was Shakespeare’s inspiration for Othello, it is worth noting the admiration and anxiety that he put into the hearts of the English courtiers he visited, including probably, Shakespeare.

So when Shakespeare wrote Othello, the black population was growing, a noble moor was getting attention at court, and he might have been living and working around black people in his company, so he might have been trying to present a black character in a positive light based on his experiences. So what does the text of Othello say about black people, and what Shakespeare might have thought about them?

The dilemma anyone reading or performing Othello faces is the fact that he is both a noble general who loves his wife, and also a jealous savage murderer. As I have mentioned, Shakespeare might have known black actors and some claim that he had a mistress of color, but that doesn’t guarantee that he was aware of the oppression and degradation of the African people. So why did he choose to make the character black in the first place?

Part II: What does the play say about race?

Shakespeare’s source for Othello was an Italian short story by Giovanni Battista Giraldi. It has some small differences in plot, but Othello’s character is identical to Shakespeare’s, though he is never referred to by name; instead he is only called “The Moor.” Still, Giraldi mentions The Moor’s bravery, skill in battle, and initial reluctance to believe the devilish ensign who deceived him. Therefore Shakespeare emphasized all the positive qualities of his original source.

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/cinthios-gli-hecatommithi-an-italian-source-for-othello-and-measure-for-measure

Othello is not presented as a savage person; we see him as somebody who comes from somewhere else. It is impossible to pin down exactly where he comes from because his descriptions of his past are very vague and sometimes seemingly contradictory. As Germaine Greer mentioned in the TV documentary Shakespeare Uncovered, what we do know is that he definitely assimilated into Venetian culture, presumably converted to Christianity from whatever religion he had, and rose through the ranks by fighting the Ottoman Turks. This means Othello is waging war against Muslims. What I am trying to construct here is to determine based on what we know about black people from Shakespeare’s time and what we know about stereotypes of foreigners and others and the journey of Othello, is his murderous jealous behavior, as a result of nurture, (which is to say Iago‘s devilish manipulation), or by nature. In other words, did Shakespeare write a racist play that condemns interracial marriages due to the barbarous nature of Moors?

Othello is not the only jealous character in the Shakespearean cannon; Claudio in Much Ado, Postumous in Cymbeline, and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale all accuse their wives of infidelity and all of them threatened to kill those unfortunate (and innocent women). This means that Shakespeare is not implying that jealousy is inherently connected to race. Looking at the text of Othello, one interpretation I can offer is that it is less about black people and more about how white people perceive them. Just like in Shakespeare’s source, very few people in the play call Othello by his name, they call him a term that defines him by his race. In addition, though Othello never talks explicitly about his race and is very cryptic about his life, plenty of characters make assumptions about what being a moor means:

“To the gross clasps of a lascivious Moor” – Iago 1.1.126)

“An extravagant and wheeling stranger / Of here and every where” – Rodrigo 1.1.136-137). [Scene Summary]

[Brabantio speaking to Othello] “To the sooty bosom / Of such a thing as thou — to fear, not to delight” (1.2.70-71).

One reason Iago is able to manipulate the people close to Othello is because he can manipulate the prejudices that they have about black people. He knows that they will believe anything he says, as long as it falls in line with their preconceptions. In addition, since Othello isn’t a native Venetian, Iago can manipulate Othello’s inexperience with Venetian society:

IAGO

197 Look to your wife; observe her well with Cassio;

201 I know our country disposition well;

202 In Venice they do let heaven see the pranks

203 They dare not show their husbands; their best conscience

204 Is not to leave’t undone, but keep’t unknown.

OTHELLO

205 Dost thou say so?

IAGO

206 She did deceive her father, marrying you;

207 And when she seem’d to shake and fear your looks,

208 She loved them most.

OTHELLO

208 And so she did.

IAGO

208. go to: An expression of impatience.

208 Why, go to then;

209. seeming: false appearance.

209 She that, so young, could give out such a seeming,

210. seal: blind. (A term from falconry). oak: A close-grained wood.

210 To seel her father’s eyes up close as oak,

211 He thought ’twas witchcraft—but I am much to blame;

212 I humbly do beseech you of your pardon

213 For too much loving you.

OTHELLO

213. bound: indebted.

213 I am bound to thee for ever.

IAGO

214 I see this hath a little dash’d your spirits. Othello, Act III, Scene iii.

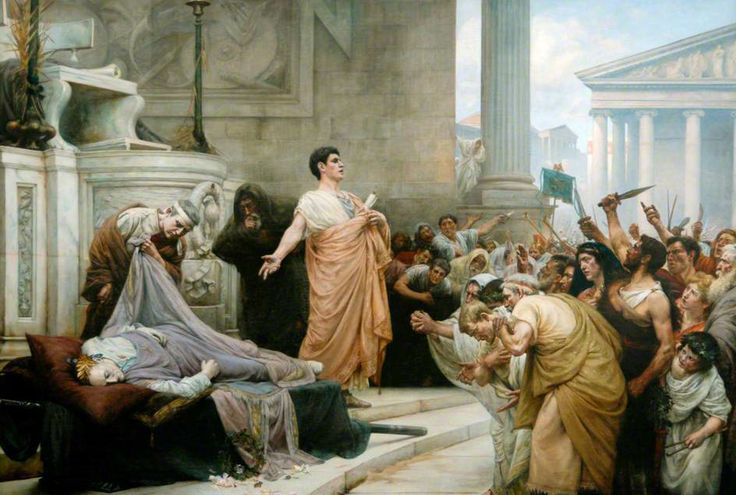

Plenty of actors, scholars, and directors have made the case that Shakespeare’s plays aren’t racist, but they do have racist elements. In Othello’s case, the racism of other people destroys an otherwise honorable man.

https://youtu.be/gMZRP9hrbY4

The Murder: As a counter argument, though Othello is not the only jealous hero in Shakespeare, he is the only black one, and he is the only one who kills his wife onstage. Therefore, even if Othello is a positive black figure at first, his behavior at the end of the play does give an impression of a man who has become a savage murderer, and it is important for the audience to question how watching a white woman being murdered in her bed by a black man makes them feel, especially when everyone else in the play has said he is a barbaric, lustful, foreign beast.

Part III Production History

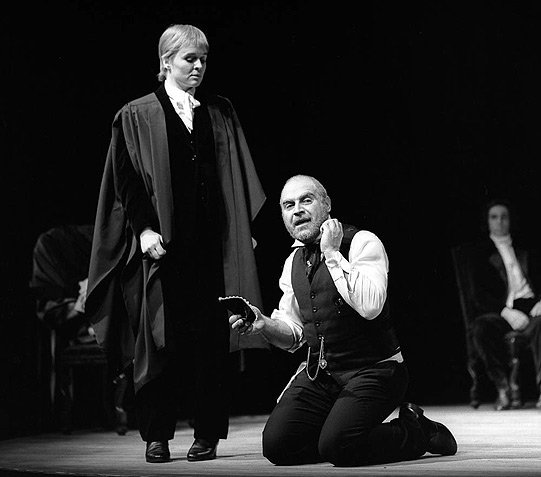

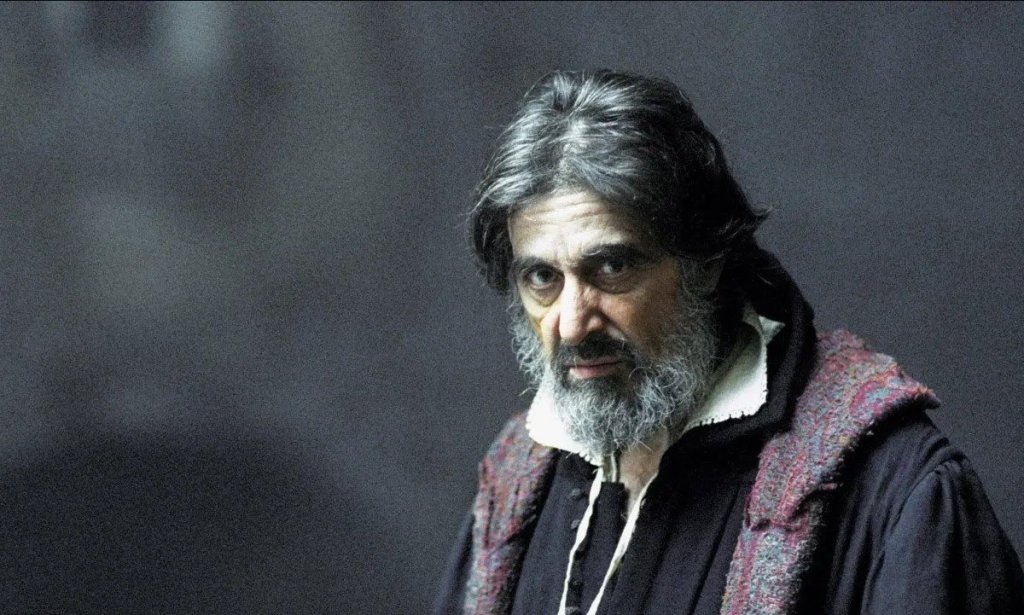

Although there’s a decent argument that Othello isn’t a racist play, it’s production history has been harrowed with racism. For 250 years the role wasn’t even played by black actors. Even on film, the first black man to play Othello was Laurence Fishburne in 1995.

Going further back, the first genuine black actor to play Othello was Ira Adrige, an African American who moved to England in the mid 1800s. Above is a copy of the playbill for his celebrated touring performance of Othello in 1851, which inspired very powerful and polarized reactions: https://youtu.be/92Z-4eJj7Wo

Audiences have had incredibly powerful reactions to seeing real black actors in the role. Some have expressed disgust and racist hatred, (especially in the scenes with Desdemona), some have expressed praise, sometimes they have ignored the race issues entirely. Reportedly Joseph Stalin loved the play and participated enjoyed Othello’s strength and stoicism (Wood 254). Ultimately the context of a production often determines more of the audience reaction than the actors’ performances.

To end where I began, I’m well aware that it’s impossible to truly tell whether Shakespeare was racist, and it’s equally futile trying to pin down what he was saying about race when he wrote the part of Othello, but it is worth considering how the part is connected to changing views of race and racial relations. Ultimately it is up to the actors and director to decide whether Othello is a good man, a racist stereotype, or anything else. That is the beauty of Shakespeare’s complicated and compelling characters, they can translate beyond time, and maybe even race.

For an excellent discussion of this complex topic, click the link below: https://youtu.be/puMpPNtYxuw

: https://youtu.be/puMpPNtYxuw

◦ Sources:

Books:

TV:Shakespeare Uncovered: Othello

Magazines:

BBC News: Britain’s first black community in Elizabethan London. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-18903391

Web:

http://www.blackpast.org/perspectives/black-presence-pre-20th-century-europe-hidden-history

http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/619

https://allpoetry.com/The-Dark-Lady-Sonnets-(127—154)

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/william-shakespeare/9758184/Has-Shakespeares-dark-lady-finally-been-revealed.html

http://www.peterbassano.com/shakespeare

https://www.matthieuchapman.com/scholarship

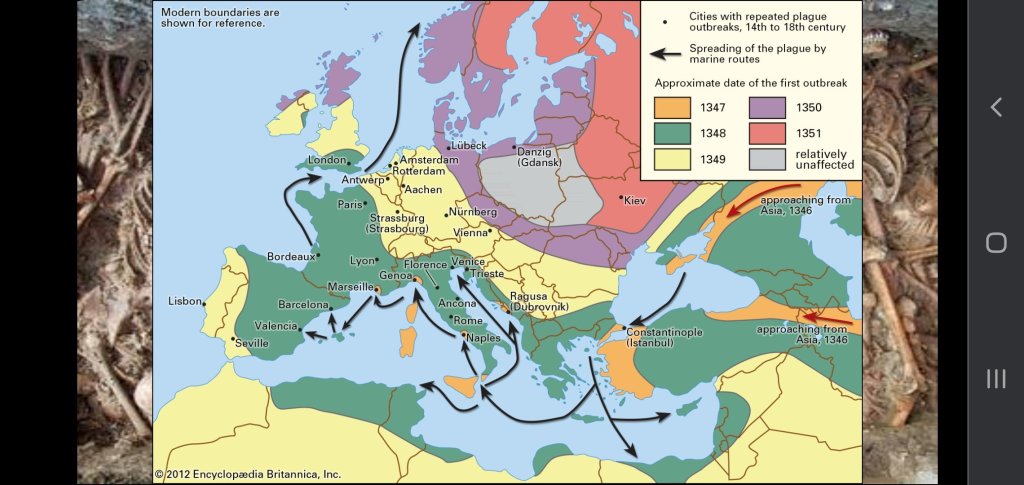

• Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.

• Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.