I know Halloween is over, but since I am doing a research project on the Salem Witch Trials, I thought I would trace the history of Witch Hunts from Shakespeare’s day to Salem:

I know Halloween is over, but since I am doing a research project on the Salem Witch Trials, I thought I would trace the history of Witch Hunts from Shakespeare’s day to Salem:

I made a digital escape room for Macbeth, as part of my Outschool.com class, “Macbeth: An Immersive Educational Experience,” which you can register for at a discount this week only. I’m presenting this digital escape room as an activity for teachers to teach their student’s knowledge of the plot of the play and use their observation and research skills to escape from a “cursed castle.”

In a normal escape room, you are locked in a room and have to follow clues and solve puzzles in order to find a series of keys, codes, and combinations to unlock the door and get out of the room. In a digital escape room, you solve online puzzles and use passwords and key codes to unlock some kind of digital content.

My escape room is designed to test your knowledge of the play, give you a chance to learn about the history behind it. Most escape rooms use the a variety of locks such as:

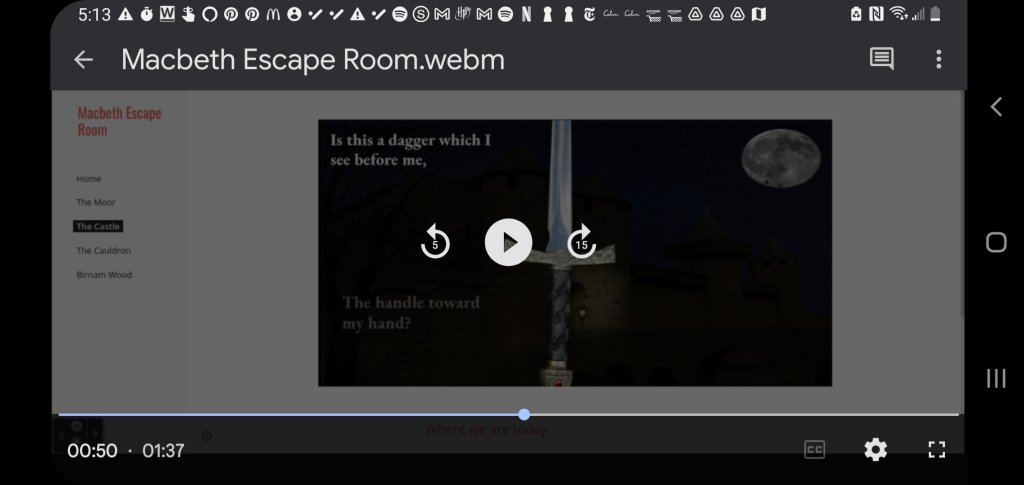

A digital escape room uses these concepts and adapts them to work within the context of a website or other digital experience. For example, I made a direction lock based on the direction a dagger points and made a short animation of a dagger with the text of Macbeth’s famous dagger speech.

The student has to surf through five webpages to find the answers to the puzzles, then imputs the answer in a Google form. Once he or she unlocks all six puzzles, they are permitted to leave the witches’ castle. Here’s a preview of the puzzles:

There’s a website called Flippity which allows you to make little online puzzles so I embedded it on one page of my website. In this case, it has six locks that you have to unlock by typing answers to trivia questions related to “Macbeth,” such as “What object appeared to Macbeth before he killed the king?” The final lock requires you to read a short article on the curse of Macbeth, so you can enter it on the website.

There’s a website called a magic mirror, which if you click on the mirror, it hyperlinks to an image that spells out the next answer for the Google form.

I wanted to teach the students about verse scantion and what an iambic pentamer iine is. I wanted to get the class to learn the pattern of unaccented beats (which Shakespeare scholars mark with a U), and accented beats marked with a /, as in the couplet below:

To get the students to practice making an iambic pentameter line, I embedded a Google Slides presentation in the website which has pictures of unarmed and armed soldiers. A key indicates that you are to count the soldiers and input the U/U/ pattern into the Google Form:

So, there’s a preview of the Digital Escape Room I hope this inspires you to try this type of activity in your class. If you want to use this activity, shoot me an email and I’ll give you a teacher’s guide. Please also consider signing up for my Outschool.com class!

I’m very excited! As some of you know, I wrote a piece about Orson Well’s 1936 Federal Theater Project production of “Macbeth,” set in Haiti. This was an important moment in theater history, and helped keep theater and African Americans employed during the Great Depression, so it deserves to be remembered. Imagine my joy when I found out that there’s an independent movie about the creation of this show! Below is the trailer. If you go to https://www.voodoomacbethfilm.com/, you can see the screening dates. Check it out when it comes to your town!

This video is part of my Outschool course “Macbeth: An Immersive Horror Experience.” I use it to explain the plot of the play before playing a game and an escape room to test the student’s knowledge. Let me know in the comments what you think of it, and if you like it, please consider signing up for the course on Outschool.com

Just in time for October, I’m offering an online class for kids ages 13-18 about Shakespeare’s most spooky and cursed play:

If you follow this blog you know I’ve written a lot about this play before. Though this class will be more like a game where I teach the class using multimedia, games, and a digital escape room!

I’ll start by speaking to the students in character as Shakespeare, and tell them the story of Macbeth using a multimedia presentation.

I will then test the students’ knowledge with a fun quiz that was inspired by the popular mobile game Among Us. As you know, the game is similar to a scene from the play, so I thought it would be an appropriate way to test the kids’ knowledge.

The final part of the class is a digital escape room I’ve created. I don’t want to give too much away, and you can’t play it unless you sign up for the class, but let’s just say it’s fun, spooky, educational, and challenging!

If you want to sign up now, the course is available every weekend in October, and then by request after that. Register now at Outschool.com. if you take the course, please leave me a good review.

Hope to see you soon!

I’ve been working on a remote learning class for Outschool.com where I take some of the audition advice I wrote in Creating A Character: Macbeth, and some of the other acting posts I’ve published over the years. This will be a weekly virtual acting course for kids ages 13-18, starting September 12th at 10AM EST.

This class will outline the tools and techniques of Shakespearean acting such as projection, articulation, and imagination. Each We’ll also go over Shakespeare’s own advice on acting in his play “Hamlet: Prince of Denmark.” The course will culminate with the students choosing their own Shakespearean monologues and scenes, which they can use going forward in auditions, school plays, and classes.

The best thing about the course is that each week builds on the previous week’s experience, but you don’t need to go to all of them. I’ll be flexible and work with the student’s schedule so everyone gets as much out of the class as possible.

If you’re interested in signing up, go to Outschool.com. If you have any questions, email me by clicking here:

Hope to see you online soon!

My family is quickly falling in love with the hugely popular online gaming sensation “Among Us,” which if you don’t know, is a strategy game similar to the game “Werewolf,” where a lone player, (known as The Impostor), tries to ‘kill’ a group of people without arousing suspicion. Just like the kids game in “Among Us,” whenever someone gets murdered, the others try to figure out the identity of the murderer.

The fun and drama of the game definitely comes from the paranoia that the players inevitably experience, not knowing whom to trust. Is the murderer over there? Was she the murderer? Is she lying about where she was just now? And most importantly, who is next?

Shakespeare’s Macbeth taps into the paranoia not just of people afraid of being murdered, but even the paranoia of the murderer himself!

Analysis of the scene: Act II, Scene iii:https://youtu.be/Pr4KmK9eXO0

After Macbeth kills the king and he and his wife cover up the blood, there is a council meeting where Ross, Macduff, Malcom, and Donaldbane try to figure out what happened. Macbeth and Lennox accuse the sleeping guards, but not everyone is sure. Watch this “interview” with the character Malcom, the crown prince, who suspects foul play: https://youtu.be/LIWjh59oBS4

While Malcom is nervous and suspicious, Lady Macbeth is the picture of composure, and grief (at least, while in public): https://youtu.be/yFJ5HYWdeMo

Macbeth’s strategy is pretty clever: blame someone else, then get them killed before anyone can question them. Very similar to the strategy I’ve seen impostors try in the game. In fact, there’s even a player who goes by the username: “King Macbeth.” He then justifies killing the guards by claiming that seeing them there threw him into a murderous rage, and he killed them to avenge Duncan’s death:

Macbeth

O, yet I do repent me of my fury,

That I did kill them.

Macduff

Wherefore did you so?

Macbeth

Who can be wise, amazed, temperate and furious,

Loyal and neutral, in a moment? No man.

The expedition of my violent love

Outran the pauser, reason. Here lay Duncan,

His silver skin laced with his golden blood;

And his gashed stabs looked like a breach in nature

For ruin’s wasteful entrance — there, the murderers,

Steeped in the colors of their trade, their daggers

Unmannerly breeched with gore. Who could refrain

That had a heart to love, and in that heart

Courage to make’s love known?

As a final bonus, here’s the entire play summarized through Among Us gameplay: https://youtu.be/HIp9MI5jpeI

Thanks very much for reading! If you liked this post, please consider signing up for my new “Macbeth” online class via Outschool.com. One really fun part of the class will be a quiz on “Macbeth,” inspired by Among Us!

I’m giving a lecture Sunday about “Macbeth” and its relation to real magical traditions. Accordingly, I’ve looked up records of real witchcraft trials. Below is a database of cases from 1602-1635. “Macbeth” was supposedly written around 1605, so these cases are pretty close to the time period. It’s a fascinating, and sometimes gruesome look at the methods used to try people (mostly women) for an “invisible crime,” around the same time Shakespeare was dramatizing that crime onstage: http://witching.org/production/brimstone/detail.php?mode=city&city=London%20(Newgate%20Prison).

Let me begin by admitting that this post was harder to write than my Christmas post because pre Christian traditions are harder to pin down. In addition, to give you my standard disclaimer, I don’t believe it’s really possible to definitively know how or if Shakespeare celebrated Halloween, but since the history of Halloween is long and fascinating, and since Shakespeare’s plays influenced that history, I feel it’s worth exploring.

Part I: Origins of Halloween

Almost every culture on Earth has a middle fall celebration that calls to mind the bounty of the harvest, and the inevitable approach of winter. Most of our Halloween traditions are based on the ancient European festival of Samhuin.

What is Samhuin?

Over 2,000 years ago, the Celts inhabited much of the British Isles. They believed in many gods and spirits that controlled nature and the seasons. To thank the gods for the harvest the Celts gave them offerings like apples, and threw parties to celebrate the gods’ bounty.

When the Romans conquered the Celts, they co-opted some of their religious practices. For instance the tradition of giving apples as offerings to the Roman goddess Pomona. This tradition of course, evolved into our modern Halloween tradition of bobbing for apples. Honoring the harvest also went hand in hand with darker traditions; ones inspired by fear of death, decay, and evil spirits.

With the Sun dying and the Earth growing cold in late October, cultures like the Celts and the Romans feared that evil fairies and ghosts could cross over into our world. In particular the Celts believed that around the night of October 31st, the veil between the living and the dead was the thinnest.

Samhuinn was a liminal time between our world and the Otherworld. It’s a night when the souls of dead loved ones as well as spirits and fairies – the aos sí in Irish mythology and aes sídhe or sìth in Scottish mythology – could come through to visit. Deceased family members were honoured with seats at the evening feast, and offerings of milk and baked goods were left at the front door for the Fairies.

At some point people decided to dress up as the spirits to ward them off, and this evolved into our modern day trick or treating.

These traditions did not die once England became Christian, (after it was conquered by the Romans), they simply translated into a different form. Halloween actually translates as “All Hallows Eve,” a Catholic celebration of of dressing up as pagan spirits and giving offerings of the harvest to honor Catholic saints as well as departed love ones.

Part II: What might Shakespeare have Done on Halloween?

Although Shakespeare never directly mentions Halloween, he lived in a world that kept many of these folk traditions alive. Shakespeare was the grandson of a farmer and his father was a devout Catholic, so he probably was brought up in these ancient Halloween traditions. He probably would have attended some kind of harvest festival to celebrate the bounty of the summer, and might have put food out for his departed family members.

Samhain is still heralded by the baking of kornigou, cakes baked in the shape of antlers to commemorate the god of winter shedding his ‘cuckold’ horns as he returns to his kingdom in the otherworld. On the Isle of Man in the Irish sea, the Manx celebrate Hop-tu-Naa, which is a celebration of the original New Year’s Eve and children dress as scary beings, carry turnips and go from home to home asking for sweets or money.

Source: https://theancientweb.com/2010/10/the-origins-of-halloween-part-1/

Call me a softie but I really like the idea of Shakespeare baking treats like soul cakes for neighborhood kids or telling scary stories about a bonfire. The kornigou is more commonly known as the Soul Cake, and it’s still popular today. It’s even been immortalized in song:

You can even make it yourself: www.cardamomdaysfood.com/recipe/soul-cakes/

Another tradition was dancing around ancient Celtic burial mounds. According to tradition, these mounds were home to spirits and Fairies, and could be portals to the land of the dead. In Irish folklore, poets and storytellers had the power to pass between these two realms. Maybe Shakespeare himself visited such a mound in his youth and was inspired to write about the fairy queen Titania and the hobgoblin Robin Goodfellow. Archeologists are still learning about these ancient ruins today (source: Smithson.com)

• Theater

The most tantalizing ancient Halloween tradition is mumming, a kind of amateur theater practiced by the ancient Celts. Like modern Sunday school plays the plays were a religious ritual designed goal to honor the gods and the harvest.

Mumming, a type of folk play, was used to tell traditional Samhuinn stories about battles or the winter goddess Cailleach (meaning “old hag”), who began winter by washing her hair in the whirlpool of Corryvreck.

For a modern example of this of these traditions you can look at the Edinburgh fire festival which preserves the kind of mumming that the Celts might have done on Samhuin and Shakespeare might have seen. It’s highly ritualistic, immersive, and the characters have spooky similarities to some of Shakespeare’s plays.

To give you an idea of how mumming might have influenced Shakespeare, watch this trailer for the 2017 Edinburgh Fire Festival:

• What you can see in the trailer:

1. Keening- the wild women screaming as a way to lament, honor, and guide the dead. Characters like Constance in King John have many similar qualities.

2. The fight between the Summer King and the Winter Lord. Many Celtic stories dramatize the change of seasons from summer to winter as a battle. Even the duel between King Arthur and his young son Mordred could be seen in this context. In another interesting interpretation, Jennifer Lee Carroll in her book Haunt Me Still, interprets this mummers play as a pagan retelling of the story of Macbeth.

3. You can see brightly colored figures some designed to honor the changing of the seasons, and wild, animalistic people, presumably playing the roles of the Fairies, goblins, or other creatures that appear on Samhuin. It’s not much of a stretch to see these figures as the Fairies of Midsummer Night’s Dream, or the witches of Macbeth.

Part III: What did Shakespeare mention about Halloween?

Ghosts appear in five of Shakespeare’s plays. We see reference to all kinds of Fairies, goblins, and spirits and even a couple times people dressing up to ward off evil. In Titus Andronicus, the queen of the Goths disguises herself and her sons as spirits of revenge and go to Titus’ house to torment him, and then the old man Titus tricking them into coming to his house, where he takes his revenge.

One Shakespeare play that I think perfectly encapsulates the Halloween traditions of the English countryside is Merry Wives Of Windsor, specifically the scene in which Falstaff is tormented by a ghost story.

In the play, the fat, drunk knight Sir John Falstaff has been trying to seduce two married women, Mistress Page and Mistress Ford. Page devises a plan to scare and humiliate Falstaff, by dressing up her husband as the terrifying ghost of Herne the Hunter:

• 4.4 MISTRESS PAGE

• There is an old tale goes that Herne the hunter,

Sometime a keeper here in Windsor forest,

Doth all the winter-time, at still midnight,

Walk round about an oak, with great ragg’d horns;

And there he blasts the tree and takes the cattle

And makes milch-kine yield blood and shakes a chain

In a most hideous and dreadful manner:

You have heard of such a spirit, and well you know

The superstitious idle-headed eld

Received and did deliver to our age

This tale of Herne the hunter for a truth.

Herne the Hunter is a real medieval legend about a man who was hanged for poaching deer in Windsor park and now haunts the forest with horns on his head. Not only does Master Ford dress as Herne, The witty housewives dress the neighborhood children like Fairies and instruct them to pinch the fat knight and burn him with lit candles. Essentially this scene is a Shakespearean trick or treating moment with a ghost story to boot. Plus as Mistress Page mentioned, the ghost haunts Windsor towards the the oncoming of Winter, so it’s not entirely unlikely that it would be that this scene was originally played around the time of Halloween.

How did Shakespeare contribute?

Scholars describe Shakespeare’s mind like a magpie, taking myths, legends, history, and books to come up with his own plays. As you have seen, the ancient traditions of Halloween had a powerful effect on Shakespeare’s plays. But, did he contribute to those traditions himself? I would say yes in a big way. First of all the image of Hamlet holding a skull has inspired many other Halloween images:

David Tennant in Hamlet, RSC 2008

Jack Skellington in The Nightmare Before Christmas, 1993.

But I think Shakespeare’s greatest contribution to how we celebrate Halloween are centered within the witches of Macbeth.

Though Shakespeare by no means invented the concept of witchcraft, he did popularize the idea of the wicked witch, and helped form our modern view of what a witch is. The image he created in Macbeth

More than that, I would argue that the modern wicked witch would be all but silent without Shakespeare. When you think of what a witch might say, besides a series of high pitched cackling, what do you think of? Probably you think of this:

Or this:

Shakespeare’s bizarre and cryptic language helped inspire countless other interpretations of witches, and thus, a way for audiences to deal with the temptations that lurk in our hearts.

In conclusion, we don’t know how Shakespeare celebrated Halloween or even if he did to begin with; Halloween and Shakespeare’s life are both frought with mystery and legend, but one thing is dead certain; Halloween would not be the same without him. He absorbed the ancient rituals of the Celts and Romans and crafted some modern Halloween ideas and images that endure to this day.

Sources

https://www.historic-uk.com/CultureUK/Halloween/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/15169373

Thanks very much for reading! If you liked this post, please consider signing up for my new “Macbeth” online class via Outschool.com. One really fun part of the class will be an escape room where you use your knowledge of Macbeth to escape a cursed castle: