Today is March 15th, a day that history still bewares, because of the infamous day when armed, violent conspirators went to the Senate and attempted to overthrow elected rulers. For obvious reasons, this put me in mind of the heinous actions of another group of conspirators stormed another Senate and tried, unsuccessfully, to overthrow democracy.

January 6th, 2021 (which, coincidently, was Twelfth Night, one of my favorite Shakespeare-themed holidays), was a tragedy for multiple reasons. The protestors broke windows, destroyed furniture, defaced statues, broke into both chambers of Congress, and probably would have harmed lawmakers, in a violent protest of both the US presidential election and the Senate vote in Georgia that week.

Let me be clear, this was sedition and treason and everyone involved should be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. Anyone who says otherwise is blatantly attacking our cherished democracy, and spitting in the face of the rule of law. Unfortunately, Republicans in both chambers have been unwilling to condemn their actions for fear of alienating their base. If this is what the Republican party has come to, the party doesn’t deserve the name. A republic protects the right of the people to elect its representatives and dedicates itself to the peaceful transition of power. Left unchallenged, groups like this will bring anarchy and tyranny to our country.

How do I know this? Because it happened before. Shakespeare has long dramatized real historic events where people rise up against their governments (for better or worse). In all cases, whether protesting a famine, a war, or a cruel tyrannical usurper, the riots never accomplish anything except bringing chaos and bloodshed. Sometimes these ignorant rioters are goaded by charismatic powerful figures, but these upper-class characters are only exploiting the rioters, using their violence as a way to get power for themselves. So, let’s examine the language, tactics, and effects of rioters in three of Shakespeare’s plays: Julius Caesar, Henry VI Part III, and Sir Thomas More:

Example 1: Julius Caesar

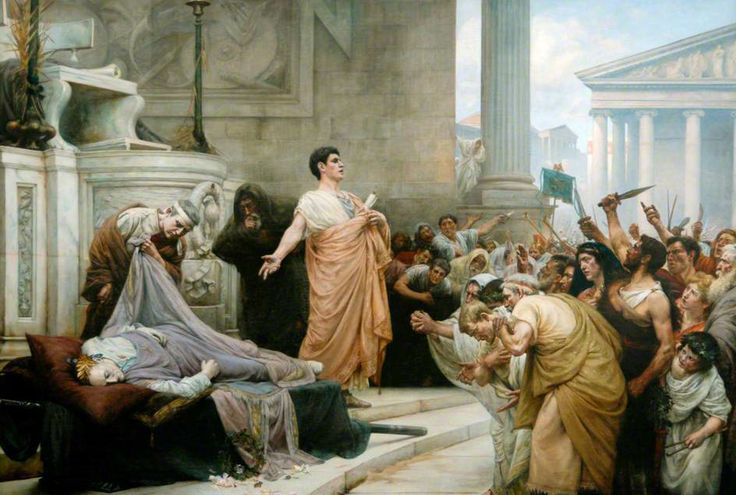

As I covered before in my “Friends, Romans, Countrymen,” post, during Antony’s famous funeral speech, he galvanizes the Roman crowd, first to mourn Caesar, then to revenge his death. How do they do this? By burning the houses of the conspirators and rioting in the street. They even kill a man just because he has the same name as one of the conspirators:

https://www.rsc.org.uk/shakespeare-learning-zone/julius-caesar/story/timeline

What does this violence accomplish? Nothing. Caesar is still dead. Brutus is still alive (though on the run). Antony merely wished to punish Brutus, and get the mob to hate him while he secretly cheats them out of their money. In Act Four, Antony becomes the de facto ruler of Rome because he leveraged his performance at the funeral, and uses his newfound powers to take money away from the citizens that Caesar promised to give them in his will. He manipulated them for his own purposes and duped them for political power.

Example 2: Jack Cade in Henry VI, Part ii.

Henry VI is the only king in English history to be crowned twice, deposed twice, and buried twice (Saccio 91). As the play begins, King Henry has already lost France, lost his mind, and lost the respect of his people. Around 1455, John Hardyng wrote a contrast between Henry’s father and himself. He laments that Henry the Fifth died so soon and then exhorts Henry to keep the quarrelsome lords in his government from warring among themselves.

Withstand, good lord, the outbreak of debates.

And chastise well also the rioters

Who in each shire are now confederates

Against your peace, and all their maintainers

For truly else will fall the fairest flowers

Of your great crown and noble monarchy

Which God defend and keep through his mercy.

(Excerpt from Harding’s Chronicle, English Historical Documents, 274).

Henry’s political ineptness was why Richard of York challenged his claim to the throne. Though Richard had little legal claim as king, he believed himself to be better than Henry.

In Shakespeare’s play Henry VI, Part ii, York tries to get the people’s support by engineering a crisis that he can easily solve. York dupes a man named Jack Cade to start a riot in London and demand that the magistrates crown Cade as the true king.

York and Cade start a conspiracy theory that Cade is the true heir to the throne and the royal family suppressed his claim and lied about his identity. Cade starts calling himself John Mortimer, a distant uncle of the king whom York himself admits is long dead:

And this fell tempest shall not cease to rage

Until the golden circuit on my head,

Like to the glorious sun's transparent beams,

Do calm the fury of this mad-bred flaw.

And, for a minister of my intent,

I have seduced a headstrong Kentishman,

John Cade of Ashford,

To make commotion, as full well he can,

Under the title of John Mortimer.

Just like Cade and his rebels, the January 6th rioters were motivated by lies and conspiracies designed to crush their faith in their legitimate ruler. Even more disturbing, these rioters are pawns in the master plan of a corrupt political group. York doesn’t care that Cade isn’t the real king; he just wants to use Cade’s violence as an excuse to raise an army, one that he can eventually use against King Henry himself.

Similar to York’s lies and conspiracy-mongering, many Republicans have refused to accept the legitimacy of Joe Biden’s election, and some are actual proponents of Q Anon conspiracies!

A lot of Republicans deserve blame for fanning the flames of rebellion on January 6th, but arguably former President Trump deserves most of the blame. Even Rush Limbaugh admitted that Trump spread a huge amount of conspiracy theories without believing in any of them. He does this because he wants Americans to be afraid of imaginary threats that he claims he can solve. What’s easier to solve than a problem that doesn’t exist? Much like York, Trump tried to hold onto power by pressuring his supporters to pressure the Capital, feeding them lies about election fraud, and a secret democratic Satanic cult. Thus radicalized, they resolved to do what Cade’s mob did: “Kill all the lawyers.” Unfortunately, there are a lot of lawyers in the Senate.

As Dick the Butcher points out, most people don’t actually believe Cade is truly John Mortimer, they are just so angry at the king and the oppressive English government, that they are willing to follow him in a violent mob to take their vengeance upon the monarchy. This is why they try Lord Saye and execute him just for the crime of reading and writing! Similarly, the mob attacking the capital was made up of die-hard conspiracy adherents, and people just angry at the Democratic Party.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2021/01/20/qanon-trump-era-ends/

Like I said before, Cade and his mob is just a pawn in the machinations of York. Eventually the king’s enforcer, Lord Clifford convinces most of them to abandon Cade, and Cade himself dies a humiliating death- on the run from the law and starving, Cade is murdered by a farmer after trying to steal some food. After Joe Biden became the 46th President, many of the conspiracy group Q-Anon, who had many prominent members in the January 6th riot, began to disbelieve and abandon the conspiracies of the group. However, as this news story shows, some Q-Anon supporters are die-hard adherents and will never abandon their conspiracy theories, and some, like York’s supporters, are being recruited by other extreme groups. Sadly, as York shows, sometimes a riot is a rehearsal for another riot. In Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part III, York finally amasses an army and challenges the Lancastrians in all-out war. Hopefully, the US government will hunt down and arrest these violent insurrectionists before they have the chance to do the same.

Example 3: Sir Thomas More

In the unfinished play “Sir Thomas More, a racist mob again attempts to attack London. This time they have no political pretenses; they want to lynch immigrants who they believe are taking English jobs. As I said in my “Who Would Shakespeare Vote For?” post, More’s speech is a perfect explanation of why this behavior cheapens and denigrated a country’s image, and weakens its ability to command respect from the rest of the world. Last time I posted a video of Sir Ian McKellen speaking this speech, but this time.. well just watch:

• Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.

• Plague carts like in Monty Python (Dreary) carried plague bodies out of the city and burned them.