As you know, I’m a huge fan of Shakespeare and the Broadway musical “Hamilton,” so I was delighted when I saw this post on “Good Tickle Brain!”

Original Post Here: check them out for Shakespearean humor!

As you know, I’m a huge fan of Shakespeare and the Broadway musical “Hamilton,” so I was delighted when I saw this post on “Good Tickle Brain!”

Original Post Here: check them out for Shakespearean humor!

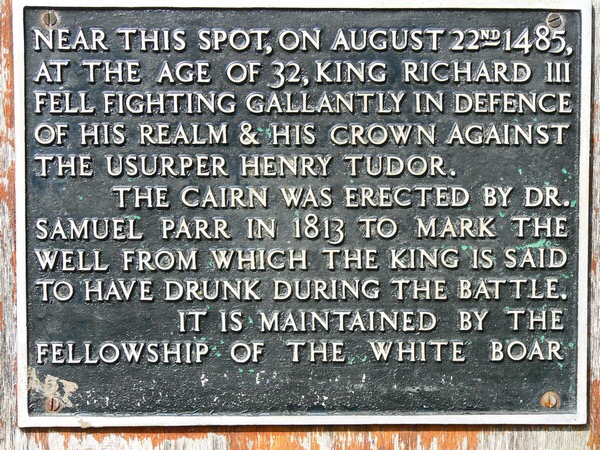

To begin wrapping up our Richard III month, I thought it might be appropriate to speak a little about the battle that ended the real Richard’s life, the Battle of Bosworth Field, August 22, 1485.

What does Shakespeare Say about the battle:

KING RICHARD III

Come, bustle, bustle; caparison my horse.

Call up Lord Stanley, bid him bring his power:

I will lead forth my soldiers to the plain,

And thus my battle shall be ordered:

My foreward shall be drawn out all in length,

Consisting equally of horse and foot;

Our archers shall be placed in the midst

John Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Earl of Surrey, Shall have the leading of this foot and horse. They thus directed, we will follow In the main battle, whose puissance on either side Shall be well winged with our chiefest horse. This, and Saint George to boot!

What think’st thou, Norfolk?

NORFOLK

A good direction, warlike sovereign.

Richard III, Act V, Scene iii.

This speech matches very well with what the chronicles mention about the battle. In those days the English archers were more deadly than their cavalry, so Richard probably wanted to pick off as many soldiers as possible with the archers, then mow the rest down with his charge toward Henry.

Contemporary Accounts, (courtesy of the Richard III Society). The most complete, and unbiased account I could find was Polydore Virgil, which is also likely the one from which Shakespeare got his information. You’ll notice that it mentions the long line of foot soldiers and horsemen, and the mention of the Duke of Norfolk commanding one of Richard’s forces.

‘The day after King Richard, well furnished in all things, drew his whole army out of their encampments, and arrayed his battle-line, extended at such a wonderful length, and composed of footmen and horsemen packed together in such a way that the mass of armed men struck terror in the hearts of the distant onlookers. In the front he placed the archers, like a most strong bulwark, appointing as their leader John, duke of Norfolk. To the rear of this long battle-line followed the king himself, with a select force of soldiers.‘Meanwhile … early in the morning [Henry Tudor] commanded his soldiery to set to arms, and at the same time sent to Thomas Stanley, who now approached the place of the fight, midway between the two armies, to come in with his forces, so that the men could be put in formation. He answered that Henry should set his own men in line, while he would be at hand with his army in proper array. Since this reply was given contrary to what was expected, and to what the opportunity of the time and greatness of the cause demanded, Henry became rather anxious and began to lose heart. Nevertheless without delay he arranged his men, from necessity, in this fashion. He drew up a simple battle-line on account of the fewness of his men. In front of the line he placed archers, putting the earl of Oxford in command; to defend it on the right wing he positioned Gilbert Talbot, and on the left wing in truth he placed John Savage. He himself, relying on the aid of Thomas Stanley, followed with one company of horsemen and a few foot-soldiers. For all in all the number of soldiers was scarcely 5,000, not counting the Stanleyites of whom about 3,000 were in the battle under the leadership of William Stanley. The king’s forces were at least twice as many.

‘Thus the battle-line on each side was arrayed. As soon as the two armies came within sight of each other, the soldiers donned their helms and prepared for the battle, waiting for the signal to attack with attentive ears. There was a marsh between them, which Henry deliberately left on his right, to serve his men as a defensive wall. In doing this he simultaneously put the sun behind him. The king, as soon as he saw the enemy advance past the marsh, ordered his men to charge. Suddenly raising a great shout they attacked first with arrows, and their opponents, in no wise holding back from the fight, returned the fire fiercely. When it came to close quarters, however, the dealing was done with swords.‘In the mean time the earl of Oxford, afraid that in the fighting his men would be surrounded by the multitude, gave out the order through the ranks that no soldier should go more than ten feet from the standards.

‘Thus the battle-line on each side was arrayed. As soon as the two armies came within sight of each other, the soldiers donned their helms and prepared for the battle, waiting for the signal to attack with attentive ears. There was a marsh between them, which Henry deliberately left on his right, to serve his men as a defensive wall. In doing this he simultaneously put the sun behind him. The king, as soon as he saw the enemy advance past the marsh, ordered his men to charge. Suddenly raising a great shout they attacked first with arrows, and their opponents, in no wise holding back from the fight, returned the fire fiercely. When it came to close quarters, however, the dealing was done with swords.‘In the mean time the earl of Oxford, afraid that in the fighting his men would be surrounded by the multitude, gave out the order through the ranks that no soldier should go more than ten feet from the standards.

When in response to the command all the men massed together and drew back a little from the fray, their opponents, suspecting a trick, took fright and broke off from the fighting for a while. In truth many, who wished the king damned rather than saved, were not reluctant to do so, and for that reason fought less stoutly. Then the earl of Oxford on the one part, with tightly grouped units, attacked the enemy afresh, and the others in the other part pressing together in wedge formation renewed the battle.

While the battle thus raged between the front lines in both sectors, Richard learnt, first from spies, that Henry was some way off with a few armed men as his retinue, and then, as the latter drew nearer, recognised him more certainly from his standards. Inflamed with anger, he spurred his horse, and road against him from the other side, beyond the battle line. Henry saw Richard come upon him, and since all hope of safety lay in arms, he eagerly offered himself for this contest. In the first charge Richard killed several men; toppled Henry’s standard, along with the standard-bearer William Brandon; contended with John Cheney, a man of surpassing bravery, who stood in his way, and thrust him to the ground with great force; and made a path for himself through the press of steel.

‘Nevertheless Henry held out against the attack longer than his troops, who now almost despaired of victory, had thought likely. Then, behold, William Stanley came in support with 3,000 men. Indeed it was at this point that, with the rest of his men taking to their heels, Richard was slain fighting in the thickest of the press. Meanwhile the earl of Oxford, after a brief struggle, likewise quickly put to flight the remainder of the troops who fought in the front line, a great number of whom were killed in the rout. Yet many more, who supported Richard out of fear and not out of their own will, purposely held off from the battle, and departed unharmed, as men who desired not the safety but the destruction of the prince whom they detested. About 1,000 men were slain, including from the nobility John duke of Norfolk, Walter Lord Ferrers, Robert Brackenbury, Richard Radcliffe and several others. Two days after at Leicester, William Catesby, lawyer, with a few associates, was executed. Among those that took to their heels, Francis Lord Lovell, Humphrey Stafford, with Thomas his brother, and many companions, fled into the sanctuary of St. John which is near Colchester, a town on the Essex coast. There was a huge number of captives, for when Richard was killed, all men threw down their weapons, and freely submitted themselves to Henry’s obedience, which the majority would have done at the outset, if with Richard’s scouts rushing back and forth it had been possible. Amongst them the chief was Henry earl of Northumberland and Thomas earl of Surrey. The latter was put in prison, whree he remained for a long time, the former was received in favour as a friend at heart. Henry lost in the battle scarcely a hundred soldiers, amongst whom one notable was William Brandon, who bore Henry’s battle standard. The battle was fought on the 11th day before the kalends of September, in the year of man’s salvation 1486, and the struggle lasted more than two hours.

‘The report is that Richard could have saved himself by flight. His companions, seeing from the very outset of the battle that the soldiers were wielding their arms feebly and sluggishly, and that some were secretly deserting, suspected treason, and urged him to flee. When his cause obviously began to falter, they brought him a swift horse. Yet he, who was not unaware that the people hated him, setting aside hope of all future success, allegedly replied, such was the great fierceness and force of his mind, that that very day he would make an end either of war or life. Knowing for certain that that day would either deliver him a pacified realm thenceforward or else take it away forever, he went into the fray wearing the royal crown, so that he might thereby make either a beginning or an end of his reign. Thus the miserable man suddenly had such an end as customarily befalls them that for justice, divine law and virtue substitue wilfulness, impiety and depravity. To be sure, these are far more forcible object-lessons than the voices of men to deter those persons who allow no time to pass free from some wickedness, cruelty, or mischief.

‘Immediately after gaining victory, Henry gave thanks to Almighty God with many prayers. Then filled with unbelievable happiness, he took himself to the nearest hill, where after he had congratulated his soldiers and ordered them to care for the wounded and bury the slain, he gave eternal thanks to his captains, promising that he would remember their good services. In the mean time the soldiers saluted him as king with a great shout, applauding him with most willing hearts. Seeing this, Thomas Stanley immediately placed Richard’s crown, found among the spoil, on his head, as though he had become king by command of the people, acclaimed in the ancestral manner; and that was the first omen of his felicity.’

-Polydore Virgil, c. 1500. Reprinted from the Richard III Society:

http://www.r3.org/richard-iii/the-battle-of-bosworth/bosworth-contemporary-tudor-accounts/

What most people can agree:

Above- infographic of Richard’s battle wounds, courtesy of Lifescience.com

To conclude, even Shakespeare admits that Richard was a great commander, who lost the battle when his own soldiers betrayed him, and he was piteously murdered by the man who took over the crown from him. It’s a good thing that the real King Richard’s remains were discovered in 2012, and we now know more about the real man in addition to the myth.

RIP Richard.

I was going to review this movie, but I’m quite impressed by Mr. Galgren of Channel Awesome’s take on it. I think this review is a great summary of how this movie cleverly adapts Shakespeare’s play in a 20th century context, and how incredible Sir Ian’s performance is! Enjoy the review, and see the movie if you get the chance!

This amazing BBC series does all of Shakespeare’s histories, and for Richard III, they cast one of the greatest young Shakespearean actors: Benedick Cumberbatch!

The Hollow Crown: Richard III

As a bonus, here is an interview with the star, explaining why the play is still relevant today:

Before we continue our exploration of Shakespeare’s “Richard the Third,” I would be remiss if I didn’t spend a little time talking a little about the real Richard Plantagenet, Duke Of Gloucester and king of England from 1483-1485. I have to get this out of the way first and foremost: although “Richard III” is classified as a history play, most of the facts in it are untrue, or severely exaggerated. In this post I will try to separate the character from the man to try and make clear what Shakespeare changed from history and why.

First, a video bio I created:

The facts are these:

-He was a real English monarch who reigned 1483-1485.

– Richard was the younger brother of King Edward IV, and helped his brother take the crown away from King Henry VI, in a series of battles known as The Wars Of the Roses.

– The battles got their name because Richard’s family (the House Of York), used a white rose as its symbol, while King Henry’s faction used a red rose.

– Like Ned Stark in Game of Thrones, Richard was the undesputed “Warden Of the North,” in charge of crushing a potential Scottish invasion.

– In April of 1483, Richard’s brother King Edward IV died. As Lord Protector of England, Richard was entrusted to take care of the country, and Edward’s two sons (the new heirs to the throne). In late May, Richard arrested three lords on suspicion of treason while he guided the two princes to London. Within one month, the two princes were publicly declared illegitimate by the Archbishop, thus making Richard the new king.

– Sometime during Richard’s two year reign, Edward’s sons disappeared. Many believe they were murdered and Shakespeare’s sources named James Tyrrell and Michael Forrest as the murderers, acting under King Richard’s orders. In 1674, the skeletons of two boys believed to be the princes were discovered in the Tower Of London. The remains were interred by King Charles II. So far, nobody has confirmed if the remains belong to the princes or what happened to the young boys.

-Richard was defeated and murdered by Henry Tudor, Earl of Richmond at the Battle Of Bosworth Field on August 22, 1485. His successor founded the House Of Tudor which included Henry VIII, Mary I, Edward VI, and Queen Elizabeth I.

-in 2015, historian Phillipa Langley discovered King Richard’s remains in a parking lot in Leicester

Few contemporary sources survive from Richard’s day, so it’s unknown whether Richard did kill the princes. Even more mysterious, although he did work to depose a king, oppress the Scots, and take the throne from Edward’s kids, some sources claim Richard was actually a just and good king. In the lack of facts, Richard’s legend continues to grow

Reality check

-After finding his skeleton, scientists discovered that Richard was not deformed, although he did have scoliosis. Thomas Moore added the hump, while Shakespeare added the withered arm.

-After finding his skeleton, scientists discovered that Richard was not deformed, although he did have scoliosis. Thomas Moore added the hump, while Shakespeare added the withered arm.

– There is no physical evidence that Richard killed the two princes, and many others wanted them dead, including Henry Tudor himself!

-Richard also probably was a good king according to some contemporary accounts, as you can see in this video with Monty Python’s Terry Jones:

Why were the facts twisted?

– Shakespeare’s main source was a history by Sir Thomas More, who was 12 at the time of Richard’s reign. More was Henry VIII’s royal chancellor, so he couldn’t afford to be nice to Richard either. More’s history set the groundwork for Shakespeare’s portrayal of Richard as a deformed monster.

The point is, people have known for centuries that Shakespeare’s Richard is no more true than the myth of Robin Hood. Even Laurence Olivier admits before his film even starts that this story has been “scorned in proof thousands of times.” Nevertheless, like Robin Hood, this story is part of the fabric of English society, and it still has value as a cautionary tale about corrupt governments, and how one man may lose his soul (and a horse) in pursuit of power and revenge.

Even today, people continue to gain power by manipulating fear, hatred, and religion, which is why we as a society need Shakespeare’s Richard. The play is so universal it was re interpreted in 2007 as “Richard III: an Arab tragedy.” Shakespeare’s Richard is so close to today’s dirty politicians that we have TV shows on both sides of the Atlantic inspired by him, (more on that later). And Richard himself is so compelling a character that centuries of great actors, cartoon characters, and even occasional rock stars have wanted to emulate him.

The lesson of the story is that a single demagogue can gain control of a corrupt system if we let him. Hitler, Saddam, Trump. It’s no accident that Olivier chose to play Richard right as the war was ending in Europe, and his popularity in that role rose exponentially after post war Britain saw the parallels between the “honey words” of Richard, which captivated England, to Hitler’s fiery rhetoric, which nearly destroyed it. The larger point through all four plays of Shakespeare’s history cycle, (not just “Richard III,”) is that greed and cruelty within one family can lead to chaos on a large scale, especially when it’s the royal family.

For more information:

Books:

Websites:

The Richard III Society: Official website of the society dedicated to preserving the memory of Richard III.

Historic UK: Short biographies of English Monarchs

Leicester Cathedral’s Richard III Page: http://kingrichardinleicester.com See pictures and read about Richard’s final resting place, and how his remains were found, and re-interred.

Westminster Abbey- The tomb of most English kings and queens for over 1,000 years:

http://www.westminster-abbey.org/our-history/royals?start_rank=1

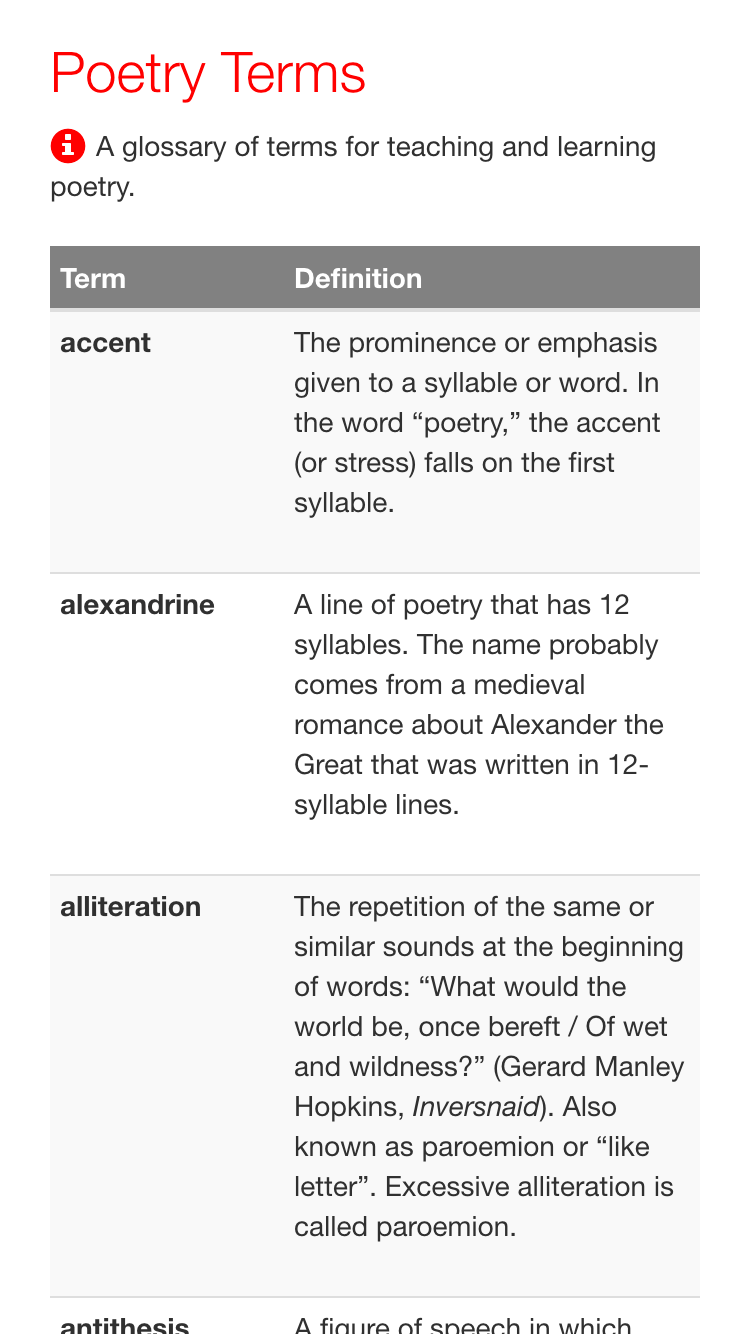

As I said before, my criteria for these apps was “Free, functional (educational or useful in life,) and fun.”

6. Shakespeare by Shmop: incredible! This is a study guide for your phone of tablet. There are separate apps Hamlet, Macbeth, and R&J. Each one features a glossary, analysis, quotes, study questions, you get the idea. You can cover a lot of the play with this app. My favorite feature is “Why Should I Care?” This is a short essay that compares the themes and ideas of the play to modern life. Excellent app, and the website is great too for students and teachers: http://www.shmoop.com

7. Shakespeare for kids–

I believe nobody is too old or too young to enjoy Shakespeare, so I tried to find a Shkespeare app for young children and came up with this. To be honest, I was disappointed in this one; it’s basically an app version of Irene Lamb’s book “Tales From Shakespeare”. It consists of short summaries of the plays intended for children. There are no study guides, no quotes, and the games have nothing to do with Shakespeare. My advice, get the book, or go to these sites:

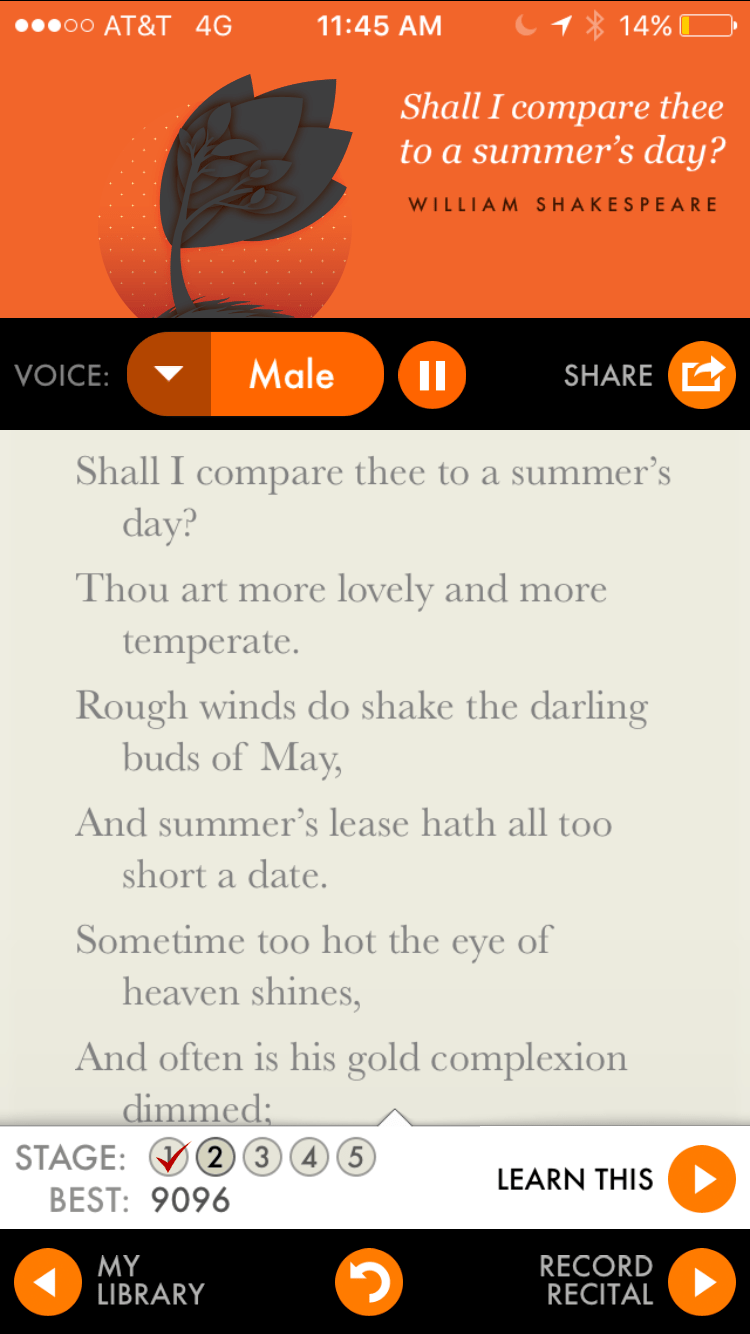

8. Poems By Heart Made by the Penguin Publishing Co, it’s designed to help you learn a poem by quizzing yourself, one line at a time, (or one word if necessary). Friendly and enjoyable.

9. Soliloquy by playshakespeare.com.

As you might expect, this app is a database of Shakespearean speeches. I normally don’t advocate actors learning speeches out of context without reading the whole play, but this app is useful for the professional actor on the go, who needs to pull out a speech in a hurry. It’s sort of a digital monologue portfolio. You can find a good speech, save it, then pull it out when you need to study it. There’s also a pro feature that allows you to edit the speech if it’s running long. What I really like is the fact that each speech is conveniently classified by gender/ genre/ length, and the helpful tips for young actors picking a good speech.

10. Shakespeare by Play Shakespeare.com

Well now we come to the end of the free Shakespeare app list I’ve compiled. Now what? I would recommend downloading Shakespeare by Playshakespeare.com, then BURN THE LIST! This is the most incredible Shakespeare app I’ve ever seen! It has tons of free and pay- only features and I’ve listed a few below:

Much like this blog, I recommend this app to Shakespeare lovers of any age!

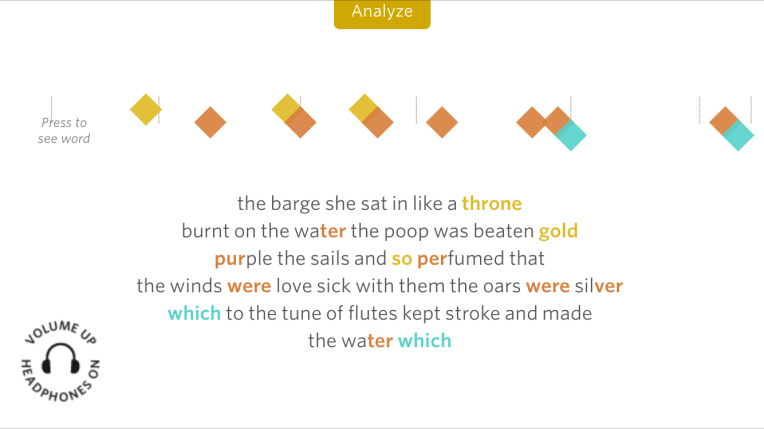

One more bonus review: this isn’t an app, but it’s a website created by Joel Eastman and Erik Hinton of the Wall Street Journal. Its purpose is to analyze the awesome lyric complexity of the Broadway musical “Hamilton.” http://graphics.wsj.com/hamilton/

The website uncovers the use of assonance, alliteration, near-rhymes, mid-line rhymes, and other strokes of Lin-Manuel Maranda’s lyrical brush. The best part is that you can feed any text you want into the website, and it will use the same algorithm to show you its lyrical elements, so I’d recommend using it as a tool to study Shakespeare. You’ll find that the Bard of Avon and Snoop Lion aren’t as different as they might seem.

So there you are, a few fun, friendly, and free tools for exploring the work and life of a timeless English playwright. As The Bard might say: “Sirs, betake you to your tools,” for such apps as these are only as good as the person who uses them.

Hi everyone,

Introducing our new Play of the Month: Shakespeare’s dark history play about murder and corruption, Richard III. First, a short presentation I made that introduces the characters and themes of the play.

Second, a quick, funny summary of the play from the Reduced Shakespeare Company

Hung be the heavens with black, yield day to night! – William Shakespeare

One of the greatest classical actors of our time has gone to his great reward, which I hope includes a “good show” from Shakespeare himself. Most people know Alan Rickman as the slimy Professor Snape, or the evil Hans Gruber, or the cheating husband from “Love Actually,” but a generation ago he was a Shakespearean acting phenomenon at the Royal Shakespeare Company, playing such roles as Jaques, Hamlet, and Achilles. As much as I love Harry Potter, I think it’s wrong to remember such a versatile actor for only one role, so here’s a retrospective of his work that I found this morning. Guardian Tribute to Alan Rickman

“Good night sweet prince, and flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.”

The venerated Shakespearean actor, Sir Antony Sher, once said with frustration while he was acting at the RSC that, “even the best Feste is less funny than the worst Malvolio.” I actually have a rare insight into these two roles since I’ve played them both! So allow me if you will to present you with some insights I’ve gained into these two characters that are very much polar opposites. Although they are as different as night and day, they form the central comic premise of the whole play, and have some truly hilarious moments!

Me. as Malvolio, Wooster. High School 2002

Me. as Malvolio, Wooster. High School 2002I played Malvolio when I was a senior in high school; he was my first principal Shakespearean role. My director chose to set the play in the 1940s and he re-purposed the kingdom of Illyria as the Hotel Illyria, with Malvolio as the concierge or lead butler in charge of all the hotel maids and other housekeepers. This not only made the play more accessible to a 2002 audience, it also really helped me understand Malvolio’s role: he is first and foremost a snob who is obsessed with efficiency and pleasing his mistress Olivia (in this version the owner of the hotel). I would soon also discover that, although Malvolio is certainly snobby and can be a bit of a killjoy, he also has qualities that make him appealing to everyone who has ever felt put down or bullied, and that’s what makes him a complex and endearing character today.

Richard Briars as Malvolio

Richard Briars as MalvolioSome notes on the character: Malvolio’s name means “unsatisfied desire”- somebody who aspires to be what he is not. I find the relationship between Feste and Malvolio interesting because the two are partially defined by how each one is unlike the other. Feste is a clown, hired by the nobles to help them have a good time. He is described as “a merry fellow who cares for nothing.” In other words, Feste never takes anything seriously, except making a living with his jokes and songs. Malvolio is the exact opposite- he is also a servant, but he is a steward, in charge of running the Countess Olivia’s household. As such, he is obsessed with efficiency, commanding respect, and pleasing his mistress through his obsequious manner.

Like the Joker and Batman, both characters live according to an opposing viewpoint; Feste is a chaotic, happy-go-lucky sort, while Malvolio has a strict code of behavior which he expects everyone to follow. Their opposing world views bring them into conflict every time they meet. Plus, in most productions Feste is wearing brightly colored clown apparel or “motley wear,” while Malvolio is dressed in black. I’m not saying Malvolio is anywhere near as cool as Batman, but Malvolio can be just as sanctimonious. His journey is how he goes from being the trusted household servant, to a raving madman, to at last the Spectre at the feast at Olivia’s wedding.

I think the appeal of the character, which balances out the aforementioned snobbery, is that Malvolio is also a nerd: he dreams of becoming a count, he tries to make friends, but he does so by working far too hard at his job and not knowing how to fit in. This is why we inevitably feel sorry for him at the end of the play when he begs to know why his tormentors have locked him in a dark room, treated him like a lunatic, and made him think his lady was in love with him only to utterly destroy his hopes. The balance between the Nerd and the Snob that makes Malvolio a universal and complex part, and that’s why some of history’s greatest actors have played it!

Prepping for the Role: Alec Guinness, Laurence Olivier, Patrick Stewart, Donald Sinden, Nigel Hawthorne, Richard Briars, Steven Fry- these are just some of the names of actors who have played this part over the years. The first actor to play the role was Shakespeare’s leading actor, Richard Burbage, who also played Richard III, Hamlet, and Macbeth. Here’s a sample from Burbage’s famous eulogy, which mentions some of his most famous parts:

A Funeral Elegy

On the Death of the Famous Actor, Richard Burbage,

He’s gone, and with him what a world are dead,

Friends, every one, and what a blank instead!

Tyrant Macbeth, with unwash’d, bloody hand,

We vainly now may hope to understand.

Brutus and Marcius henceforth must be dumb,

For ne’er thy like upon the stage shall come,

Vindex is gone, and what a loss was he!

Frankford, Brachiano, and Malevole.

One big decision that every Shakespearean actor needs to make is how to approach their role in a different way. To be honest, I was kind of a thief with my Malvolio- one of the first things I did was read a book by actor Sir Donald Sinden where he talks about how he delivered Malvolio’s first line, which occurs in Act I, Scene iii:

Olivia. What think you of this fool, Malvolio? doth he not mend?

Malvolio. Yes, and shall do till the pangs of death shake him:

infirmity, that decays the wise, doth ever make the 365

better fool (Act I, Scene v).

Sinden described his first line as a snobby “nyess,” as if he were simultaneously bored and embarrassed by Feste’s jokes. The director told me to act around Feste as if I were the villain in a Charlie Chaplin movie- basically to bully Feste and make him feel very small with my lines, in order to justify the revenge Feste innevitably takes on him. Like any character in Shakespeare, this is only one way to play the role, so you don’t have to agree with me.

The Gulling Scene

Malvolio’s most famous scene is called “The Gulling Scene,” the scene in which he’s tricked into thinking Olivia is in love with him. This is the moment where Malvolio goes from being a respectable prudish servant, into a raving madman. He enters full of dreams and plans to become “Count Malvolio” and creates an elaborate fantasy of what his life would be like if he married the Countess.

Act II Scene v. From Shakespeare Navigators.com

No sooner does Malvolio compete his fantasy of marrying Olivia, when lo and behold, a letter from her suddenly appears! Of course, the audience knows it’s all a trap and even worse, Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, and a boy named Fabian are watching him! It’s a moment of exquisite comedy that’s nearly impossible to get wrong.

Malvolio and the Countess, 1840 by Daniel Maclise

One question I had when I did the scene was whether Malvolio really loves Olivia, or just loves her riches and her title. As a high schooler, I chose to believe that he really does have a crush on Olivia, but is too socially awkward to tell her. Having the letter is a chance to make his feelings known, which Malvolio can get very genuinely excited about! On the other hand, as you can see above, Malvolio might just be greedy to make himself even more respected and admired, and to have the power to throw out the likes of Sir Toby, Sir Andrew, and Maria. Malvolio’s revenge fantasy is also fun to watch, since we know he’ll be punished for it later.

Part of the fun involved in the scene is that it’s basically a “play within a play,” a device that Shakespeare used to great effect in Hamlet, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Love’s Labor’s Lost, and both parts of Henry the Fourth. I think it’s the charm of seeing a character as he really is, Malvolio shows you his fantasies and creates a whole world in the middle of the orchard. Meanwhile, you feel complicit as you watch the people watching him, who could just as easily be part of your audience.Workshop on Twelfth Night and Bullying

On the other hand, the scene has also been called an example of bullying, since Sir Toby and Maria are using the letter to manipulate then humiliate Malvolio. Remember, Malvolio dresses like a fool and act like a fool in front of Olivia in Act III because he believes it will please the Coubtess. Basically Toby and Maria are Catfishing Malvolio, which can seriously hurt psychologically, as anyone who has been deceived over the internet knows. Plus, it ruins Malvolio’s reputation as you can see in this clip:

Again, as a teenager, I could certainly relate to a man making a fool of himself in a vain attempt to impress a girl. Seeing a man lose his head over a girl and then have her break his heart over a prank, is in some ways truly terrible to watch; even Olivia agrees by the end of the play that the joke has gone too far.

Malvolio. Madam, you have done me wrong,

Notorious wrong.

Olivia. Have I, Malvolio? no.

Malvolio. Lady, you have. Pray you, peruse that letter.

You must not now deny it is your hand:

Write from it, if you can, in hand or phrase;

Or say ’tis not your seal, nor your invention:

You can say none of this: well, grant it then

And tell me, in the modesty of honour,

Why you have given me such clear lights of favour,

Bade me come smiling and cross-garter’d to you,

To put on yellow stockings and to frown 2550

Upon Sir Toby and the lighter people;

And, acting this in an obedient hope,

Why have you suffer’d me to be imprison’d,

Kept in a dark house, visited by the priest,

And made the most notorious geck and gull

That e’er invention play’d on? tell me why!

Olivia. Alas, Malvolio, this is not my writing,

Though, I confess, much like the character

But out of question ’tis Maria’s hand.

And now I do bethink me, it was she 2560

First told me thou wast mad; then camest in smiling,

And in such forms which here were presupposed

Upon thee in the letter. Prithee, be content:

This practise hath most shrewdly pass’d upon thee;

But when we know the grounds and authors of it, 2565

Thou shalt be both the plaintiff and the judge

Of thine own cause.

That’s the tragic part of Malvolio’s journey. We’ve all known a Malvolio, and we’ve all been him from time to time. That’s what makes him such an enduring character.