For Shakespeare’s birthday, I thought I’d re-visit one of my most popular posts, especially since the Royal Shakespeare Company is celebrating by putting on an adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s novel Hamnet:

Biography of Hamnet

Just like his famous father, we know very little about the life of Hamnet Shakespeare. Since infant mortality rates were high, we don’t know his exact birthday, only that he was baptized on February 2nd, 1582. Like most 11-year old boys, he probably had started going to school at the King Edward Grammer School, the same as his father. This means he spent long hours away from his parents learning to read and write in Latin and Greek. When he was home, he lived with his mother, his two sisters, and his grandparents in the house of Henley Street.

https://www.kes.net/about-us/history-of-the-school/

O’Farrel portrays the boy Hamnet as sensitive and somewhat lonely, which makes sense, since he probably didn’t see his father for long periods of the year; Will Shakespeare spent much of the year writing, going on tour, and performing at the Globe- he commuted from London to Stratford for most of the year. He probably only came around during Lent, Christmas, and times of plague when the theaters were closed.

1589-1596

Never mind what I know. You must go.” She pushes at his chest, putting air and space between them, feeling his arms slide off her, disentangling them. His face is crumpled, tense, uncertain. She smiles at him, drawing in breath. “I won’t say goodbye,” she says, keeping her voice steady. “Neither will I.” “I won’t watch you walk away.” “I’ll walk backwards,” he says, backing away, “so I can keep you in my sights.” “All the way to London?” “If I have to.” She laughs. “You’ll fall into a ditch. You’ll crash into a cart.” “So be it.

O’Farrell

The novel portrays Anne Shakespeare realizing that her husband is stifled and unhappy living with his parents in Stratford, and so she suggests to his father that he go to London to ‘expand the family business,’ though in reality, she wants him to go to make his fortune and find more fulfilling work. Scholars have wondered for years how Shakespeare got his start in theater- as a man with children he was legally unable to become an apprentice, and as a glover’s son from Stratford, he didn’t know anyone in London. O’Farrell solves the mystery by making him start out as a costume maker and mender for a theater company, who later became a writer and actor.

This idea of Shakespeare starting out as the company’s glove mender actually has some historical merit- records from the time confirm that many playwrights and actors were also local artisans. Men like John Webster, Richard Tarlton, Edward Kyneston, and even Richard Burbage were skilled drapers, textile merchants, haberdashers (men’s tailors) and ( like the Bottom in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,”) some of these men were weavers-turned actors (Source: Anna Gonzales) So it’s entirely possible that Shakespeare started in London by selling gloves to theaters, before selling his plays.

When Will moved to London, he lived in a number of locations throughout the city, probably because it wasn’t a safe place. Theaters were located in the same districts as bear baiting and brothels, so Will probably had to move to get away from bad neighborhoods, as this video from The History Squad illustrates:

Gloves

A glover will only ever want the skin, the surface, the outer layer. Everything else is useless, an inconvenience, an unnecessary mess. She thinks of the private cruelty behind something as beautiful and perfect as a glove.

Hamnet

https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/blogs/shakespeare-100-objects-pair-gloves/

Almost immediately after Will leaves, Anne is full of remorse. She knows his work in London will consume him and his success will make the distance between him and her even greater.

She walks back, more slowly, the way she came. How odd it feels, to move along the same streets, the route in reverse, like inking over old words, her feet the quill, going back over work, rewriting, erasing. Partings are strange. It seems so simple: one minute ago, four, five, he was here, at her side; now, he is gone. She was with him; she is alone. She feels exposed, chill, peeled like an onion.

The Plague

He wants to tear down the sky, he wants to rip every blossom from that tree, he wishes to take a burning branch and drive that pink-clad girl and her nag over a cliff, just to be rid of them, to clear them all out of his way. So many miles, so much road stands between him and his child, and so few hours left.

Hamnet

As I’ve said in previous posts, Shakespeare survived three epidemics of Plague; one in 1563, (before he was born), one in 1593, and one in 1603. In O’Farell’s novel, the germs that kill Hamnet came not from a massive outbreak, but a few germs that were transported in a box that his sister had the misfortune of opening. This frightful passage shows the grim tenacity and eve-present fear that, while England expanded and became more interconnected with the world, it also brought death and disease to and from the rest of Europe.

In the book, the plague germs that infect Judith and later Hamnet, lie inside a box with some glass beads that the Shakespeare’s ordered from Italy to decorate a pair of fancy gloves. As this video from National Geographic shows, trade routs then as now are prime spreaders of disease and even one ship that slips by can turn any box of goods into a Pandora’s Box, waiting for a poor unsuspecting girl like Judith to release it unto the world.

Hamnet’s Death

He can feel Death in the room, hovering in the shadows, over there beside the door, head averted, but watching all the same, always watching. It is waiting, biding its time. It will slide forward on skinless feet, with breath of damp ashes, to take her, to clasp her in its cold embrace, and he, Hamnet, will not be able to wrest her free.

Hamnet

In the novel, Hamnet somehow takes the plague away from his sister and dies in her place. Though it is hardly conclusive, I do find it interesting that Shakespeare stopped writing comedies about twins for another four years after Hamnet’s death, until he wrote Twelfth Night, which unlike earlier comedies like The Comedy of Errors, has a pair of twins mourning each other’s apparent death. They seem to share one soul, and one tries to resurrect the other, like Viola mourning her brother by, (in a sense), becoming her brother.

What should I do in Ilyria? My brother is in Elysium

Viola- “Twelfth Night”, Act I, Scene ii.

ELIZABETHAN FUNERAL CUSTOMS

In the book, Anne makes a winding sheet for her son. This was a cloth of linen or wool that was wrapped around dead bodies, since at the time, coffins were re-used. This must have been a somber and deeply upsetting activity for Anne.

As this quote from “The Evolution of the English Shroud” illustrates, the act of making a winding sheet was a sort of sad family responsibility, a way of ensuring that your loved ones die with dignity, and Anne clearly takes the task of making one very seriously.

The 16th-century shroud for the poor and lower middle classes was a large sheet that was gathered at the head and feet, and tied in knots at both ends, covering every part of the body. It resembled earlier Medieval practices and was a functional, yet modest way of preserving the deceased’s dignity. It was also economical, with very little cost involved, as the burial sheet was usually taken from the family home. At this point, linens dominated as the material of choice; after all, it was a biblical tradition as Jesus was wrapped in a linen cloth. Linen was also considered more fashionable than wool.

Coffin Works Archive

The Aftermath Of Hamnet’s Death (Spoilers)

She discovers that it is possible to cry all day and all night. That there are many different ways to cry: the sudden outpouring of tears, the deep, racking sobs, the soundless and endless leaking of water from the eyes. That sore skin around the eyes may be treated with oil infused with a tincture of eyebright and chamomile. That it is possible to comfort your daughters with assurances about places in Heaven and eternal joy and how they may all be reunited after death and how he will be waiting for them, while not believing any of it. That people don’t always know what to say to a woman whose child has died. That some will cross the street to avoid her merely because of this. That people not considered to be good friends will come, without warning, to the fore, will leave bread and cakes on your sill, will say a kind and apt word to you after church, will ruffle Judith’s hair and pinch her wan cheek.

The Women of Hamnet

The most unique thing about this novel is how it shows the interdependence of women in Elizabethan society. Since Shakespeare spends most of the novel away from Anne, her support system mostly comes from Will’s mother Mary, as well as Anne’s daughters, her sister, and all the other women of the town. Nowadays we do most of our socialization online and barely know our own neighbors, but in the 1590s, especially for women, community was a way of building strength where women got through things like childbirth, loss, the managing of households, and many other difficulties through their relationships with other women. This video below shows the kinds of home remedies that women would share and later write down during the Tudor period:

Other Mysteries Solved

Once Hamnet dies, Will buys her a new house, New Place so she isn’t forced to live with his parents and no longer has to live in the house where her son died. But Will’s success comes with a price- he still has to leave for London. he offers to move them there but Agnes won’t hear of it. This solves the riddle of why Shakespeare commuted between town and country for his entire career- she knows the plague that took her son literally came from London, and she won’t risk losing her daughter as well. She probably also sees London like another woman that took her husband away as well, and therefore refuses to look it in the face.

It is no matter,” she pants, as they struggle there, beside the guzzling swine. “I know. You are caught by that place, like a hooked fish.” “What place? You mean London?” “No, the place in your head. I saw it once, a long time ago, a whole country in there, a landscape. You have gone to that place and it is now more real to you than anywhere else. Nothing can keep you from it. Not even the death of your own child. I see this,” she says to him, as he binds her wrists together with one of his hands, reaching down for the bag at his feet with the other. “Don’t think I don’t.”

O’Farrell, Hamnet.

The Shakespeares’ Marriage after Hamnet

I mean’, he says, ‘that I don´t think you have any idea what it is like to be married to someone like you.’

Hamnet

‘Like me?’

‘Someone who knows everything about you, before you even know it yourself. Someone who can just loo at you and divine your deepest secrets, just with a glance. Someone who can tell what you are about to say- and what you might not- before you say it. It is’ he says, ‘both a joy and a curse.

The ugly truth that O’Farrell highlights in Hamnet is that it must have been very hard for the Shakespeares to endure Hamnet’s death, especially since Will was probably not there when it happened, and probably didn’t stay around long after burying his son. It must have been catastrophic on his marriage, sort of like this tragic moment in the musical Hamilton, where the couple mourns the loss of their son, who died in a duel trying to defend his father’s honor.

Agnes is a woman broken into pieces, crumbled and scattered around. She would not be surprised to look down, one of these days, and see a foot over in the corner, an arm left on the ground, a hand dropped to the floor. Her daughters are the same. Susanna’s face is set, her brows lowered in something like anger. Judith just cries, on and on, silently; the tears leak from her and will, it seems, never stop. — How were they to know that Hamnet was the pin holding them together? That without him they would all fragment and fall apart, like a cup shattered on the floor?

Maggie O’Farrell, Hamnet

The Second Best Bed mystery

Though Anne is angry at Will for a while, she does eventually forgive him, as evidenced by another solved historical mystery. In Shakespeare’s will he gives his wife “My second-best bed, with the furniture,” which O’Farell explains, is their marriage bed. The best bed was the one they gave to guests and was therefore newer. In the book, Will offers to replace it after Hamnet dies, but Anne won’t hear of it; although she partially blames Will for Hamnet’s death, she still loves him and her love is stronger than her grief, as is her love for her surviving daughters.

What is the word, Judith asks her mother, for someone who was a twin but is no longer a twin?

Her mother, dipping a folded, doubled wick into heated tallow, pauses, but doesn’t turn around.

If you were a wife, Judith continues, and your husband dies, then you are a widow. And if its parents die, a child becomes an orphan. But what is the word for what I am?

I don’t know, her mother says.

Judith watches the liquid slide off the ends of the wicks, into the bowl below.

Maybe there isn’t one, she suggests.

Maybe not, says her mother

Raising the Dead

At the end of the book, Shakespeare plays the Ghost of Hamlet’s father, and writes Hamlet as a tribute to his late son. We don’t know for a fact that the real William Shakespeare did this but Stratford legend says that Shakespeare played the Ghost of Hamlet’s father onstage, and this has captivated the imagination of authors and scholars alike. In any case, as Stephen Greenblatt says in his book Will In The World, Shakespeare’s father’s health faded around the same time that he wrote Hamlet. it must have been hard for Shakespeare to write a name that was one letter away from his son’s over and over again. Hamlet is Shakespeare’s longest play, and the titular character has over 40% of the dialogue, so it must have been haunting at the very least for Shakespeare to have to write his son’s name nearly 4,000 times.

Whatever he determined at the time, Shakespeare must have still been brooding in late 1600 and early 1601, when he sat down to write a tragedy whose doomed hero bore the name of his dead son. His thoughts may have been intensified by news that his elderly father was seriously ill back in Stratford, for the thought of his father's death is deeply woven into the play. And the death of his son and the impending death of his father--a crisis of mourning and memory--could have caused a psychic disturbance that helps to explain the explosive power and inwardness of Hamlet.Greenblatt,

2004, p. 8)

In the book, Anne secretly goes to London to see Hamlet onstage and is overcome with emotion. Not only does Will play a ghost as tribute to his dying father, not only does he put his son’s name onstage, he directs the actor playing Hamlet to affect his own son’s mannerisms and gestures, to use theater to bring his son back from the dead. Anne is both appalled and moved by this act- Hamnet is dead, but his story is now immortal.

O’ Farrell has done a fantastic job of taking what little we know about the Shakespeare’s lives, infusing them with some clever inferences from the plays of Will Shakespeare, and finally fleshing them out with her own Shakespearean knowledge of the human heart- how it feels to bury someone, how it feels to go through trauma and what it’s like to be part of a family and to truly love someone, even though they often fail to properly love you back. As the end of the book implies, maybe Will didn’t intend to immortalize his son and share his powers of theatrical resurrection with the world, maybe this was just his way of apologizing to the love of his life. To try to make amends for the time he lost and to express a wish that he could give her son back to her, which in a way, he does:

Hamlet, here, on this stage, is two people, the young man, alive, and the father, dead. He is both alive and dead. Her husband has brought him back to life, in the only way he can. As the ghost talks, she sees that her husband, in writing this, in taking the role of the ghost, has changed places with his son. He has taken his son’s death and made it his own; he has put himself in death’s clutches, resurrecting the boy in his place. “O horrible! O horrible! Most horrible!” murmurs her husband’s ghoulish voice, recalling the agony of his death.

O’Farrell, “Hamnet”

References

Journals

Bray, Peter. “Men, loss and spiritual emergency: Shakespeare, the death of Hamnet and the making of Hamlet.” Journal of Men, Masculinities and Spirituality, vol. 2, no. 2, June 2008, pp. 95+. Gale Literature Resource Center, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A189052376/LitRC?u=pl9286&sid=bookmark-LitRC&xid=ea79f235. Accessed 20 Apr. 2023.

Period Documents

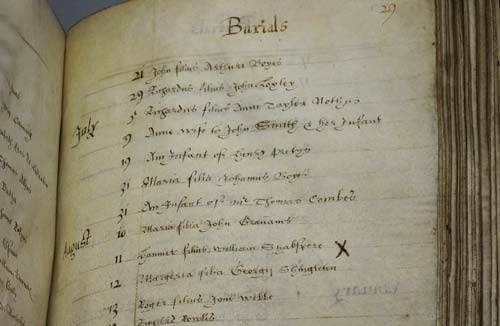

Document-specific information

Creator: Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon

Title: Parish Register of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon

Date: 1558-1776

Repository: The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Stratford-upon-Avon, UK

Call number and opening: DR243/1: Baptismal register, fol. 22v

View online bibliographic record

Web

King Edward Grammar School History: https://www.kes.net/about-us/history-of-the-school/

Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust- The Second Best Bed: https://www.shakespeare.org.uk/explore-shakespeare/shakespedia/william-shakespeare/second-best-bed/

Coffin Archive.org- The Evolution of the English Shroud: From Single Sheet To Draw-Strings and Sleeves: http://www.archive.coffinworks.org/uncategorised/the-evolution-of-the-english-shroud-from-single-sheet-to-draw-strings-and-sleeves/